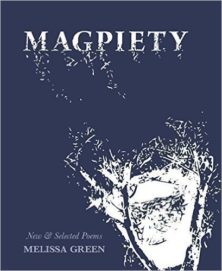

Melissa Green

Melissa Green

Arrowsmith Press ($20)

by M. Lock Swingen

When Melissa Green’s debut collection The Squanicook Eclogues was published in 1987, it received awards both from the Poetry Society of America and the Academy of American Poets. The poems in the collection were something of a shock to the English language, falling into a certain tradition—that of Gerard Manley Hopkins, Emily Dickinson, and Hart Crane, for example—which renders English into startling and unrecognizable shapes, patterns, and textures. When a reader reads Hopkins, Dickinson, Crane, or Melissa Green, in other words, she gets the impression that she is reading a foreign language, one she has never encountered before but somehow knows and understands intimately. Reading this kind of poetry resembles the kind of nostalgia you feel when you ache to return to a place you have never actually been.

The beautiful oddity of Melissa Green’s poetry, like all lyric poetry, derives from a source that is inseparable from the poetry’s music. Listen, for example, to this passage from The Squanicook Eclogues:

. . . I watch magenta clover drone

On sleeping epaulettes and know the sun-soaked earth

Is breeding still: in torpid pools, in stagnant ponds,

Rebellious nature sets her offspring quarreling

For food and territory—in-bred stone-flies riot

For their rations where the water striders run

Their useless marathons; inflammatory toads

Attempt a revolution, all in vain. In time,

The planet’s microscopic battles merge and fail,

Leaves of drying blood consumed, a season’s compost.

The ear perks up to catch the antiphony of sound clusters that Green overlays in this passage; her vowel music carries along with it an impressive consonantal repetition. Here, we can also see how the highly-wrought compression and crystallization of Green’s poetry depicts, somewhat ironically, the primal theme of nature, for the poems in Magpiety disclose Green’s communion with the changing seasons, the flora and fauna of the Massachusetts woods, and the swift current of rivers there. Describing nature’s sometimes merciless savagery, she writes:

Father, she’s made the wolf a widower and orphaned us.

The world lies ruptured to the root, its harvest crushed

By her fallen heel, a maddened heaven thrashing white

Across her unforgiven dust, and shrouded elms weighted

In mourning . . .

As in Dickinson, Green’s portrayal of nature is always caught up in ecstatic and extreme states of mental distress. Green’s gift as a poet perhaps lies in taking classical forms—the eclogue, the epic, the pastoral— and deploying their rhetorical structures to illuminate the intense introspection of a troubled mind. In an interview with Green on the poetry blog Stylus, the poet describes how the cinctures and discipline of poetic form can serve as a kind of tonic from her turbulent inner life: “In poetry the constraints of form . . . work like a series of mirrors: when the poet reaches them, they reflect back the content, meaning, sound and shape of what’s been created so far, and bend the light in the direction of what must by needs come next … Form presents the essential signposts by which you can find your way to the heart of the poem, and by which you can never be lost.” In her poem “Daphne in Mourning,” for example, Green writes:

Palm fronds have woven out the sky.

Fog has infiltrated every vein.

My hair has interlaced with vines.

Cobwebs lash their gauze across my eyes.I’ve stood so since the world began,

and turned almost to stone some years ago.

Who passes by perceives a lichened post,

my girlish features, ghostly, nearly gone.My bark is warmer than the dead’s.

Human blood still lulls the underside of leaves.

My fingers hold the very dress I loved

to dance in, when dancing mattered—and it did.

In addition to the harnessed pressure underlying the poems’ classical structures, a pressure which sublimates anguished mental states or personae, the greatest tension in the poet’s work is perhaps the insistent intensity of the language itself that threatens to supersede her themes. It is as if Green’s radical craftsmanship attempts to allegorize the density of the New England flora and fauna that the very language describes. And yet, of course, this allegory of form as content is the mark of a true poet. In her poem “Routine,” Green writes:

Tundra of the white paper. Steppes of emptiness and ice. Equipped

with crampons and picks, I notch out a poem on gneiss, frostbitten,

winded, afraid to die.

Between the typescript’s withes and raddles,

soft-nostrilled animals of meaning poke inquisitive noses through caesuras,

enjambments, metaphor, to me. I lift a serif, duck under and enter the world.

Whether Green writes of her terrifying communion with nature, Greek myth, or the trappings and anguish of her own mind, the poet demonstrates a remarkable resilience in the power and wonder of language. Thanks to the publication of Magpiety: New and Selected Poems, which amasses the best of the poet’s career into a single volume, we can now “lift a serif” with her and enter into Melissa Green’s world of awe.