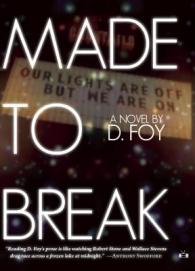

D. Foy

D. Foy

Two Dollar Radio ($16.50)

by Joseph Salvatore

In his 1993 essay “E Unibus Pluram: Television and U.S. Fiction,” David Foster Wallace defended a certain poem’s reference to Dick Clark, saying that, though it lacked “context,” it was “a reference we all, each of us, immediately get.” The “we all, each of us” with whom Wallace aligned himself evidently did not include the older generation of his writing professors, who saw such ephemeral fictional techniques as a lazy shorthand for the difficult descriptive work that realist fiction requires. It’s hard to tell if the fictional techniques of writer D. Foy, in his debut novel Made to Break (which is also set in the mid-1990s), would have made Wallace grimace or grin. For here Foy’s characters are “skinny as Fred Astaire,” their eyes have “gone Marty Feldman,” they resemble “Herman Munster’s brother.” They don’t just look like “Klaus Kinski” or even “Nosferatu,” but rather “Klaus Kinski . . . as Herzog’s Nosferatu,” or “the rat from Reservoir Dogs . . . played by Steve Buscemi.” One of his characters is “straight-up Lestat,” another has “Mary Hartman braids,” yet another has “Kris Kringle eyes.” And in a nod, perhaps, to the ur-’90s artifact, the film Reality Bites, our narrator’s feelings are described as being a “Brady Bunch thing.”

Yet what Made to Break demonstrates, and what Foy understands that Wallace’s teachers seemingly didn’t—and what perhaps even Wallace himself couldn’t have foreseen—was how far less worrisome such issues would become to a new generation of writers a couple of decades hence. For as readers will discover, Foy is no lazy technician, nor is his debut novel merely a Gen-X love letter. Employing a highly aestheticized language that calls to mind Hubert Selby, Jr. and Denis Johnson, and privileging the arc of character over the development of plot, the music of voice over the functionality of dialogue, Foy offers up a pre-apocalypse end-of-the-world tale about cannibals, mutants, corpses, survivors, road trips, lovers, and friends.

When the story opens in Oakland, CA, it’s 1995, two days before the New Year. Our narrator, Andrew, and his four closest friends—Hickory, Basil, Lucille, and Dinky—are celebrating Lucille’s new “corporate job” which pays “big-big coin.” But after their “mound of dope” becomes “just a dirty mirror,” they get in Basil’s truck and head to Tahoe, where Dinky’s family owns a cabin. As in all good stories, things immediately go wrong. A rainstorm starts; they run out of gas, have to hike for over an hour; Dinky forgets his key and Basil has to break a window to get in, which emits the stench of a dead bird’s corpse. Back in Basil’s truck in search of pre-made ice for their cocktails, Andrew and Dinky hit a mudslide. Dinky is injured, the truck is totaled, and the roads are empty, but luckily a truck comes along, its driver the aforementioned Nosferatu look-a-like, a grizzled and eccentric denim-clad veteran named Super. When Super drops them back at the cabin, the rain is worse, a flood is coming, Dinky is in bad shape, and the cabin’s phone is dead (it being the mid-’90s there are no cell phones, a plot detail convenient for Foy, but not for his characters). Getting on each other’s nerves, they decide to play Truth or Dare, a game that by novel’s end will bring on irreversible consequences.

The game sequence itself is a marvelous literary set-piece, in which Andrew ruminates on all the secrets he won’t reveal about himself and his four friends: alliances, betrayals, transgressions, family histories, some of them dramatized as flashbacks, all of them the necessary ammunition for long-awaited showdowns: “The world had changed between now and then, but the cabin had not, nor the humans in it. How is it the strangest people we know are nearly always ourselves?”

Playful and crafty with language, Foy creates characters and a world both strange and familiar (“the strangest people we know are nearly always ourselves.”). Talking about the leg he lost in Vietnam (and illuminating the novel’s larger themes), Super, who refers to himself in the first-person plural, describes how, despite such loss, he can still feel a pebble in his boot: “Tet offensive is when the foul deed done been done—well, like we said, after they snatched it off the way they did and throwed it to the dogs what with only a scratch . . . we got to feeling these itches down there, and other pains and whatnots. Our ghost foot they called it. We can feel, all right.”