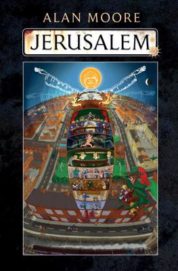

Alan Moore

Alan Moore

Liveright ($35)

by Greg Baldino

Pity the independent bookseller who has to decide where to shelve Alan Moore’s second prose work.

Twenty years ago saw the publication of Moore’s first prose book, a novel-in-stories set throughout the history of the English county of Northamptonshire. Although esoterically written in chronologically accurate first-person dialects, including an almost incomprehensible first chapter told from the point of view of a paleolithic man, it appeared close enough to the likes of Iain Sinclair and Umberto Eco to fit under the reassuring tag of “Literature/General Fiction.”

Jerusalem, however, may not be easily categorized, filed, or indexed. Its genre is its own, mixing styles and modes from contemporary, historical, and fantasy fiction.

The book is intimately personal for Moore, set in the town where he’s lived his entire life and featuring a cast based on figures from the historical to the familial, but spanning time and dimensions as readily as it spans from Chalk Lane to Scarletwell Street. Think Eastenders as a Doctor Who serial. In the opening prologue we are introduced to the modern-day descendants of the Warren clan via a memory of a childhood dream had by five-year-old Alma in 1959, who grows up to become a noted painter. In the present day her brother Mick consults with her after a near-fatal workplace injury unlocks long forgotten memories.

Apocalypse looms for the residents of The Boroughs, not in the form of a many-headed beast but in gentrification and economic starvation. But this is not another suburban romance; there’s magic in the muck and guardian “angles” in the architecture. The Warrens (and their antecedents the Vernalls) weave throughout the stories; it’s as much a family history made fantastic as it is a historical gang show. There’s madness and loss as much as there is magic and love, and sometimes all together. Cutting around through time, events and personalities are visited and revisited, monstrous grandmothers revealed as hardened survivors, pitiable eccentricity uncovered as the pathos of the everyman. An incidental character from one chapter assumes a starring roles in the next scene, and moments of tragedy become incidents of beauty and slapstick, in equal measure.

In the book’s first third, orderly time skips between chapters and dabblings in visionary metaphysics prepare the reader for the long drop down the rabbit hole ahead. At the age of three, Mick Warren choked on a cough drop and had to be rushed via a fruit seller’s cart to hospital. The journey took ten minutes during which baby Mick temporarily died. Moore has recounted this in interviews being something that happened to his own real-life brother when they were growing up, but in Jerusalem Mick’s ten minutes of inexplicably non-fatal death becomes infinitely stranger. The second part of the novel follows baby Mick’s soul running around through the higher level of The Boroughs, called “Mansoul” from John Bunyon’s The Holy War. Here he scarpers through heaven and hell with a gang of ghost children, dodging Biblical demons and eavesdropping on Lord Protectors. It’s here, where “angles” play snooker games for the fate of mankind, that Moore really gets to the teeth of Jerusalem. In the book's final third, all bets are off and anything goes, both in narrative and style.

Moreso than history, Jerusalem is a book concerned with memory and perception, both in the sense of the character’s own recollections and the communal folk-memories which inform much of the book. In interviews Moore has spoken of how much the book draws upon oral histories of the neighborhood. “I have worked with everything I remember of The Boroughs from the phraseology to local legends,” said Moore in a 2012 interview with the Northampton Chronicle, “I have drawn on my personal history, from when my family was in The Boroughs for two or three generations.”

Moore has also drawn on his decades of experience writing dialogue in a visual medium. The character voices, both spoken and internal, are fully realized and nuanced. Notorious in the comics industry for his verbose scripts—his script for the first page of From Hell describes in detail the flight paths of two flies buzzing around a dead seagull—his zeal for detail brings The Boroughs to life. One of the early characters to have their day chronicled is Marla, a junkie prostitute. In a society which degrades and dehumanizes both sex workers and addicts, a “crack whore” like her becomes a punchline, an unmourned “unfortunate.” But for forty pages Moore pays religious attention to Marla’s thoughts and actions, her observations of the world and the hurt she carries around with her.

Despite having a writing career stretching back to the late ’70s, Moore’s prose output is sparse. The comics industry in which he founded his career runs at its best like a workplace comedy of exaggerated incompetence, and at worst like a gangster ponzi scheme. As a result, out of the almost forty years of work he produced in the medium, much of it is either out of print or out of his ownership, and all of that work is collaborative. Even the bulk of his non-comics work has involved other participants, from his spoken word performances with David J and Tim Perkins to his recent forays in independent cinema. With only his own words to fill out over a thousand pages, Moore has no one to shoulder the creative load beside himself. By the same token, he has no limits to the work save his own; in that sense, Jerusalem is Moore off the leash and over the fence.

One of the best things about Jerusalem is that there’s no romantic valorizing of The Boroughs’ residents. This is not a Horatio Alger story where anyone “rises above their station”—except in the second section wherein characters literally rise above their station into a higher mathematical plane of existence. Rather, the book raises questions of how the poor are made poorly, how the social construction of class is treated as scientifically essentialist, and what that does to a people. The worth of the Boroughsians has always been in there, is in there still, but is stripped away and cast down into the refuge incinerators of political history. Here, Moore does what he can to reverse the flames, offering escapism as poetic decolonization.

One of the lives restored in the first section is Henry George, an ex-slave who moved to Northampton some years after emancipation and worked as a rag-and-bone man, collecting scrap on a bicycle with rope tires. According to Moore, Henry was a real person on those streets, but his is a story that can only be passed along by word of mouth; there is no Who’s Who for the underclass of days past. Henry’s episode is one of the most emotionally affecting of the book’s. On discovering that the pastor who wrote the song “Amazing Grace” lived in the neighboring town, he rides out to visit the man’s former church and possibly find his burial plot. It’s his pilgrimage, for it was that song that gave him and his kin hope under the abuses of slavery. What he finds instead is a dark truth that leaves him with no easy answers and profoundly difficult questions.

Jerusalem rides like Mr. George between the two towns of fantasy and realism. There are ghosts, time travel, magic, and devils. There’s compassion and cruelty, and madness aplenty. There’s death, loss, and heartbreak; there’s occasionally hope, and a remarkable amount of persistence. Time itself is both the ultimate evil and the big damn hero, but as Mrs. Gibbs the deathmonger remarks before the funeral of a child she midwifed not even a year before: “It doesn’t matter if we believe these things or if we don’t. The world’s round, even if we think it’s flat. The only difference it makes is to us. If we know it’s a globe, we needn’t be frit all the time of falling off its edge.”