The Life and Work of Frank Stanford

Constant Stranger

by Greg Bachar

Really, I visualize the dead as well as the living. I visualize you

who I will never know. We are constant strangers. I imagine you, I stare at you when I write.

—Frank Stanford

Frank Stanford is a writer whose work and legacy now sit dangerously close to the edge of oblivion. Of the 11 volumes of his work that were published both during his lifetime and after his death, only two are in print today: a collection of short fiction, Conditions Uncertain & Likely to Pass Away, and a slim volume of selected poems issued in 1991, The Light the Dead See. The rest of his books are "widely unavailable," which might lead some to believe that his work is neither important nor deserving of a larger audience. Among poets and writers who have discovered Frank Stanford's work, though, just the opposite is true, as they have kept his writing alive by tracking down and sharing the rare volumes of his poetry, volumes that actually represent only a portion of the manuscripts he put together during his lifetime. For many who stumble upon Stanford's words for the first time, there is a mixture of responses—inspiration at the scope and magnitude of his work; curiosity to know more about his life; and frustration with the fact that the thousands of pages of poems, stories, essays, film scripts, and letters that make up his literary estate have, for the most part, languished in the 20 years that have passed since his death.

On June 3, 1978, Frank Stanford committed suicide by shooting himself three times in the heart with a 22-caliber pistol. He was 29 years old. His death left an indelible absence felt to this day by those who knew him, and the body of work he left behind makes his passing seem even more poignant to those of us who can only know him through his writing. The perpetuation of a Stanford "mystique," in some circles, has allowed his life and work to take on an almost mythic quality. Caused by the tendency of some critics to mistakenly point to his death as a way of understanding his writing, and by the steady disappearance of his books, this mystique has disguised the fact that, in his lifetime, Stanford was an active participant in nearly every aspect of his chosen craft (writing, publishing, speaking on his aesthetic ideas in interviews and correspondence). The Stanford mystique also does not acknowledge the fact that he did not die an unknown poet—much of what he wrote was published while he was alive by editors who recognized his talent. In addition to poetry, Stanford also wrote short fiction over the course of his life, and translated poems by Vallejo, Bertolucci, Pasolini, Follain, and Parra. If one considers the fact that there exists today, in his literary estate and the private collections of those he knew, a treasure trove of unpublished work, it becomes obvious that Frank Stanford's legacy deserves to be championed by those who would like nothing more than to see his work back in print.

Although much of the published criticism and analysis of Frank Stanford's work has been positive, some of it has wrongly suggested that his early death prevented him from finding his true writing voice and that, as a result, his work is undeveloped and immature. Nothing could be further from the truth. A close reading of his available writing—poetry, letters, fiction, and essays—reveals the presence of a confident, original voice and a personal aesthetic that was not only limited to literature, but also incorporated a deep understanding of painting, music, philosophy, and cinema. It Wasn't A Dream, It Was A Flood, a documentary made about Stanford in 1974 by him and his publisher Irv Broughton,won an award for experimental filmmaking at the Northwest Film & Video Festival. It shows a charismatic writer with a haunting voice in full control of both a flair for the dramatic and the great depth of seriousness that is at the core of much of his writing. We can only speculate as to what might have come from Stanford's imagination had he survived the demons that led him to an early exit from this world.

In an essay titled "With the Approach of the Oak the Axeman Quakes," Frank Stanford wrote: "When the poet is young he tries to satisfy himself with many poems in one night. Later the poet spends many a night trying to satisfy the one poem. My poetry is no longer on a journey, it has arrived

at its place." One hopes that this statement might one day be fulfilled with a Collected Works of Frank Stanford on the shelves of bookstores and in the hands of readers who might be moved or inspired by the words he left behind.

The Gross And The Blended Vision:

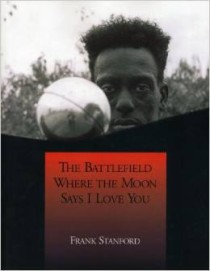

The Battlefield Where The Moon Says I Love You

by Brett Ralph

There's no reason, really, why you should have read this book, published 20 years ago in a limited edition and long out of print. Even if you could get your hands on a copy, even if you're already a fan of Frank Stanford's poems, you might be daunted by what C. D. Wright has called a "542 page poem without line integrity, punctuation or even space to facilitate breathing and eye movement, much less narrative clarity."

Still, there's every reason you should read this book and hope, as I do, that it's reprinted. By turns earthy and incantatory, down-home and harrowing, The Battlefield Where the Moon Says I Love You is also funny as hell and, to quote one of its nearly 20,000 lines, "sadder than the sea." A narrative crazy-quilt of porch swing yarns, deadly reckonings, and sexual misadventures, it could be called one of the masterpieces of Southern literature on the strength of its characters alone—narrator Francis Gildart, a 12-year-old clairvoyant; Jimmy, his hell-raising brother; Jimmy's running buddy, Charlie B. Lemon; Count Hugo Pantagruel, "the world's smallest man"; Vico, the deaf-mute who signs in his sleep; Sylvester, whom Francis calls the Black Angel; Bobo, Baby Gauge, Mama Covoe, and Tangle Eye, with cameos by Sonny Liston and Jesus Christ. It just might be our Ulysses and, were it not a poem, might justly be considered for the Great American Novel. There's certainly nothing like it in 20th-century American letters.

Still, there's every reason you should read this book and hope, as I do, that it's reprinted. By turns earthy and incantatory, down-home and harrowing, The Battlefield Where the Moon Says I Love You is also funny as hell and, to quote one of its nearly 20,000 lines, "sadder than the sea." A narrative crazy-quilt of porch swing yarns, deadly reckonings, and sexual misadventures, it could be called one of the masterpieces of Southern literature on the strength of its characters alone—narrator Francis Gildart, a 12-year-old clairvoyant; Jimmy, his hell-raising brother; Jimmy's running buddy, Charlie B. Lemon; Count Hugo Pantagruel, "the world's smallest man"; Vico, the deaf-mute who signs in his sleep; Sylvester, whom Francis calls the Black Angel; Bobo, Baby Gauge, Mama Covoe, and Tangle Eye, with cameos by Sonny Liston and Jesus Christ. It just might be our Ulysses and, were it not a poem, might justly be considered for the Great American Novel. There's certainly nothing like it in 20th-century American letters.

This is not to say Stanford's work is without ancestry. Stanford characterized his as "a vision not too unlike the ones Whitman, Blake, and the singers in the Bible had." Certainly he echoes all three when Francis prays for "the scoundrels and cowards," of which The Battlefield has plenty, constituting what our hero calls his very own "songs of the gross." Gross, most obviously, in the word's colloquial sense: vulgar, indelicate, even obscene, but deliciously so—as when Francis discovers an "electric toothbrush" hidden in the bathroom of a married woman's house; after she has seduced him and accidentally knocks him out, he awakens "naked and shivering on a large bed . . . /

she was groaning and squirming around on me with that electric toothbrush / crammed up inside her." And there's the gypsy girl, the true object of Francis's desire, masturbating in the backseat of a car at the Drive-In while he, Jimmy, Charlie B., and Tangle Eye watch through binoculars from a hillside, having been denied admission because Charlie B. and Tang are Black.

These gross songs can, likewise, be graphically violent, as in the book's many incidents of retribution, like the one where the excluded foursome avenge themselves, demolishing the Drive-In with a bulldozer as the movie plays on, its ghostly image projected on trees. Yet this sordid saga is

shot through with images that rival Lorca in their hallucinatory surfaces and symbolic depths ("chance the wise snowball that bleeds when I kiss it"). There are also incantatory passages on a par with Christopher Smart's "Jubilate Agno," as well as an unchecked flow of cultural touchstones as varied as Beethoven and Beowulf, Chuck Berry and Charlie Chaplin. While such an appetite can result in material which is sometimes gross, taken with the poem's variable textures it reveals a vision which is itself a "gross" in the other sense of the word: an undivided whole.

“The gross and the blended vision," then, points both to Francis Gildart's "God given powah" and Frank Stanford's visionary stance. In his employment of overlapping narratives, interpolated tales, fantasies of sex and revenge, dreams and waking visions, Stanford defeats time through the sheer audacity of his chronological disregard. Francis must face a similar foe, as the astronomer predicts: "you will do battle / with the notion of time you will allow your person to plumb it so your / ship may pass through it again everything has already happened." Elsewhere, Francis likens himself to

"a pursued man" hanging "on the hands of a lost clock." This "lost clock" refers to the heroic past Francis longs for, a moral system seemingly absent from his era. But it also heralds the loss of time itself. It is in Francis's battle against time and, finally, death (that clock whose ticking never ceases), that his story attains epic proportions.

Francis claims that his "dreams [are] without dominion," and the text of The Battlefield bears this out. His dreaming and waking lives conjoined,he steps out of time: "my past is simultaneous with my present." Earlier, he describes his life in language which explicitly obliterates time: "I live out my past so presently I can live with the pressure / like a diver has in his ears like the hourglass in the saddlebags / with the broken crystal." When Francis says he is a "blood brother of the fuse," he doesn't just mean the force that drives the flower or the spark that fires the machine, he means what Whitman meant when he said, "Who need be afraid

of the merge?

The fuse, the merge—whatever one calls it—celebrates the thrum of existence while signifying death itself. The body of work Frank Stanford left behind amounted to a lifelong quest for the "great poems of death" Whitman had called for a century earlier. Nowhere is this interrogation of death more substantial, and more sophisticated, than in The Battlefield Where the Moon Says I Love You. Indeed, the entire book can be read as the visionary flash that, as legend has it, attends the death throes.

Like Stanford the poet, Francis cites death as central to his song: "all I am," he says, "is a song sung to the dead by myself all my days." Soon death is no longer someone to be sung to, but a very real possibility: knocked unconscious by two men he caught stealing horses, Francis finds himself tied up "in a boat full of snakes." Rope also binds his mouth like a bit, flooding his mouth with blood; he surmises he'll be "dead in another hour if somebody don't come along." Bobo, a fisherman, shows up, ushering in a horrific and hilarious battle with a 200-pound catfish. One expects him to discover the boy, yet the passage ends with Francis still bound, the boat adrift now on the river.

Though his liberation is never mentioned, the narrative abandons the snake-filled boat for a "stray mule" which Francis mounts, his ride a motif that will recur as the poem rolls on. The beast belongs to a man called "Dark," and the ride his mule affords Francis is a singular one: a symbolic depiction of the deathward journey Francis undertook when he was placed in the boat, bound and gagged, where he has remained throughout the book'countless ecstatic episodes. Francis had foreshadowed this, saying: "I am the rider called death / I sit in the saddle with Dark the Negro / and his crazy blues sinks down like a diver into my belly of dreams."

Francis will receive, it seems, one last chance at rescue, nearly 450 pages after his plight in the boat is last mentioned: he is meditating on Charlie Chaplin (who he's convinced is his father) when suddenly Charlie B. says "untie him." Either this is mere fantasy or Francis has traveled death's trail too far to trace his way back: "I'm talking about / the other Charlie," he says, "goddamnit leave me alone I figured it out / it come to me in a dream." The dream, of course, flows on unabated; Francis has "stowed away in the ship of death" that is at once the boat in which he is left for dead, Lawrence's Stygian ship, and the fragile human body that dreams this dream and sings this song: "a vessel of death a gospel ship."

If I'm wrong—if our hero doesn't die as his hero Beowulf did—the poem remains a tour de force of imagistic power and experimental storytelling. But I like to think that, even at 26 (his age in 1974 when he first submitted this manuscript), Frank Stanford would have been dissatisfied with a book that does not reveal an architecture as remarkable as its material. His formal ambitions succeed by making death his prevailing theme and death the event that fuses this sprawling marvel into solitary fact, at once ephemeral and never-ending. This synthesis elicits a song of unparalleled breadth and beauty, one that, faced with brute mortal fact, somehow remains hopeful. "All of this," he assures us:

is magic against death

all of this ends

with to be continued

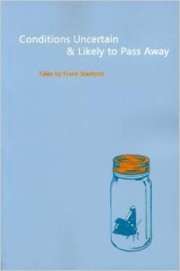

Conditions Uncertain & Likely To Pass Away

by Greg Bachar

Most, if not everything written about Frank Stanford's writing and life has been about his poetry, about Frank Stanford the poet. The truth of the matter is that he possessed an equal facility in the writing of fiction. The 11 stories in Conditions Uncertain & Likely to Pass Away (Lost Roads, $10.95) are proof that Stanford was a writer who was able to bring poetic moments and images into his narrative writing as easily as he was able to bring a sense of story, character, and place to much of his poetry.

A character in one of the tales tells us "I plan to leave behind a book of essays dealing with the imagination." Conditions Uncertain is just such a book, for each of the stories in the collection—some just a few pages long, others approaching the length of short novellas—are filled with not just an interesting assortment of strange characters, narrators, and situations, but with language-rich descriptions of the reality these characters inhabit, making a claim for the argument that the perception of the kaleidoscopic and hallucinatory nature of reality is also the most honest way of depicting it in writing. In one of his letters, Stanford wrote: "I'm off my bearing, maybe, but you understand: you know what real is, so you don't have to describe what you don't understand as surreal (like others do)."

A character in one of the tales tells us "I plan to leave behind a book of essays dealing with the imagination." Conditions Uncertain is just such a book, for each of the stories in the collection—some just a few pages long, others approaching the length of short novellas—are filled with not just an interesting assortment of strange characters, narrators, and situations, but with language-rich descriptions of the reality these characters inhabit, making a claim for the argument that the perception of the kaleidoscopic and hallucinatory nature of reality is also the most honest way of depicting it in writing. In one of his letters, Stanford wrote: "I'm off my bearing, maybe, but you understand: you know what real is, so you don't have to describe what you don't understand as surreal (like others do)."

These tales go beyond the surreal by weaving the twisting and bending webs of their narrators' stories with a chiaroscuro of dreams, nightmares, paintings, music, and stories within the tales themselves. In "McQuiston's Tale," for example, the narrator visits a blind man named Shing who claims to have a ventriloquist son with a dummy named Arimathea. Shing drinks a bottle of tabasco and, even though he is blind, likes the color blue. In "DeMoss's Tale," the narrator is taken by Silent Night, the ice truck man, to have his hair cut by Rudy in the icehouse. He puts a frozen minnow in his pocket and goes to the carnival to see The Devil. "Ansar's Tale & Luper's Note" is the story of an astronomer who goes blind and, while being taken care of by two young boys with an interest in the stars, remembers the stranger who arrived in his town when he was young and left books for him to read in his outhouse. "Merton's Tale" out-Lynches the strangest moments in a David Lynch film, as a man whose only possessions are a tape recorder and his collection of classical music spends a few delirious nights stranded by a snowstorm in a strange town.

Stanford's characters are consumed by the weight of their dreams, memories, and experiences, and the reader isn't always sure if their perceptions of reality are the right ones to hold on to. As a result, his stories are like those dreams we sometimes have that are filled with very strange people whom we have never met, but who inhabit the world we often toss and turn through in our sleep. His fiction reminds the reader that memories are as real as the experiences that shaped them, and that dreams and nightmares are experiences that can also shape or bend our perceptions of the past and present. With lines like "I felt the watch ticking against me all night like a grasshopper nailing a coffin," Stanford taps into a reservoir of surprising and jolting images and similes to create fictions that are at once disorienting and exhilarating to read. In Conditions Uncertain & Likely to Pass Away, he has successfully fulfilled one of his own character's statements: "I worked and worked the ore of my dreams until it was a fine radium."

Click here to purchase The Battlefield Where The Moon Says I Love You at your local independent bookstore

Rain Taxi Print Edition, Vol. 3 No. 3, Fall (#11) | © Rain Taxi, Inc. 1998