A History

Isaac Stanley-Becker

Princeton University Press ($35)

by Poul Houe

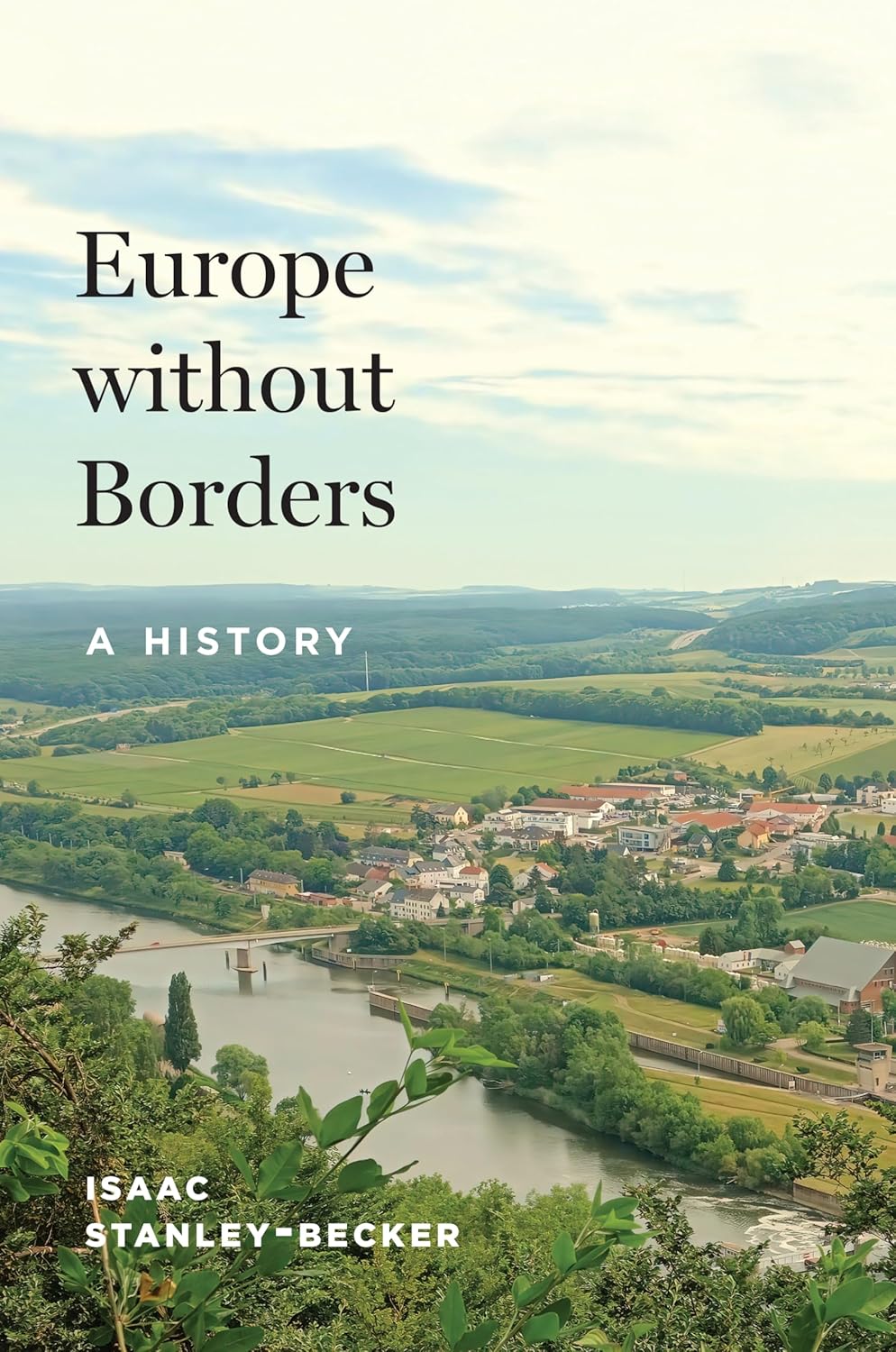

First impressions of this book may prove telling. The cover features a color photo of Schengen by the Moselle River—a village not only situated “near the tri-point border” between France, Germany, and Luxembourg, but the site where the 1985 treaty that became Europe’s official goodbye to its centuries-old borders was signed. Still, what makes this photo of a picturesque village divided by a river so pertinent to the text is the duplicity it signals: Because borders continue to play a key role in the continent’s cultural and political makeup, Isaac Stanley-Becker’s Europe without Borders is about an issue with no end in sight.

How intricate a matter the author, an investigative reporter for the Washington Post, seeks to unwrap is pronounced less by the length of the book—273 pages—than by its 107 pages of notes and bibliography. It is a meticulous undertaking, its occasional repetition justified by the persistent ambiguities and contradictions that continue to mark Europe’s grappling with its border issues and the shadows they cast on its very identity.

Money and people are the simplest expression of modern Europe’s dichotomy, but soon the simplicity multiplies and becomes hard to unravel. The Schengen ambition to extend the free market to free border crossing of people as well as goods benefits European nationals only; what about migrants, human rights, transnational freedom? Can a cosmopolitan community be European only? Stanley-Becker writes: “Schengen’s pairing of freedom and exclusion became contested. . . . My aim in exploring that project is to reveal the cruel anomalies of human movement in a world where capital and commodities travel globally with far less restraint and where national citizenship is an enduring precondition for the exercise of fundamental rights.”

From day one, the Treaty of Rome and organizations like Citizens’ Europe centered on “A Market Paradigm and Free Movement,” as Stanley-Becker titles his first chapter. But are these two sides of the same coin or polar opposites? How do the Rome Treaty’s humanist ideals match with its common market agenda? After the 1920s pan-European movements towards a borderless Europe—stalled by Hitler’s “cosmopolitan bastard” hostility—were resurrected after World War II, did they intertwine goods and people, as the Customs Union did, or were “human rights” and the “needs of the economy” balanced differently? In a famous lawyer’s words, “market freedoms . . . have something in common with human rights,” though the latter were not the “classical human rights.” A famous court case, assisted by this lawyer, “upheld uninterrupted commerce as the essence of European union” and compelled the free movement aspiration of Citizens’ Europe to be “enshrined” by “a market paradigm.”

The Treaty of Rome was first and foremost about money, and a “noneconomic defense of free movement [of people] did not exist in Community law.” So, boundaries waited to be crossed at Schengen in “A Treaty Signed on the Moselle River,” the title of the book’s second chapter about the waterway tracing Europe’s transition from “domain of empire” to “warring continent” to “transnational community.” A “new principle of freedom of movement”—beyond market needs and national borders—was now in writing, if only for European nationals.

A more generous form of balance, struck earlier by The Benelux Economic Union, “protected noneconomic rights while promoting cross-border market exchange.” This have-it-both-ways agenda contrasted especially with the French-German plan to harmonize national laws while resisting “supranational authority over external borders.” Schengen’s cosmopolitan and social space for market exchange would finally realize Citizens’ Europe and allow for nationals from all its countries, even those outside Schengen territory. At the same time, freedom had to be balanced with security; no aliens or “illegal immigrants” were to be admitted, and the right to residence was still not to be granted to just any border crosser. “Slowly, Schengen took shape as a system of dualisms” under no supranational authority. On the plus side of its account was still money, on the minus side free movement of people, hard to gauge because of Franco-German conflicts and several inconsistencies, such as Berlin’s “asylum tourism,” in sync with border failings worsened by growing public “sensitivity . . . to non-European immigrants.”

When European diplomats in 1990 made “A Return to the Moselle River” (as Chapter 3 is named), they aimed to emphasize Schengen’s European Union intent, to underscore security’s greater importance than freedom, and to fuse intergovernmental cooperation with national sovereignty. The treaty’s opposition to asylum seekers differed from the Council of Europe’s stance in that “Schengen’s ‘shadow’ darkened the ‘European fortress’”—or, as one treatymaker put it: “We tend to keep human rights for our own nationals.”

Chapter 4 deals with “A Problem of Sovereignty” or with cosmopolitanism versus nationalism. Might Schengen “become a laboratory for the breach of democratic principles and human rights,” as some parliamentarians worried? An illiberal, anti-foreigner’s “Fortress Europe,” or, in other words, “a violation of free movement and human rights.” Many nationalists saw Schengen as a mere cloak for “the global market’s penetration into domains of national autonomy and individual freedom” and claimed that its “pairing of free movement with security would cause unfreedom.” Charles de Gaulle’s prime minster warned his boss that this “European integration represented the ‘end of France.’” Conversely, the Constitutional Council assured nations that European “supranationalism would not preempt nationalism” and affirmed “the pairing of freedom with security.” Nonetheless, “realization of a Europe without internal borders has proved to be a lot more complex and complicated than its promoters had imagined,” and the time after the first treaty was signed only “made evident the ambiguities of all that Schengen had come to symbolize,” which one German politician interpreted as a “step into the European surveillance state.”

Schengen was not only “A Place of Risk,” as Stanley-Becker calls Chapter 5, but “a place of risk in a double sense.” Schengen land had become a site where police and computer surveillance were now replacing “the border barrier” with high-tech distinctions between insiders and outsiders, nationals and foreigners, asylum seekers and undesirables, to mention just one “racial marker.” The benefits of free movement came at a price, and Stanley-Becker dwells on the gap between supranational border-policing and true internationalism. Schengen had become “a place of risk” and its free movements questionable.

The book’s sixth and last chapter is devoted to the consequences as experienced by undocumented migrants, spelled out in the title “A Sans-papiers Claim to Free Movement as a Human Right.” These are people whom nativists saw emerging from the “shadows of illegality to seek recognition,” mobilized as a “countermovement to the animus against non-Europeans aroused by the opening of borders.” Further muddling Schengen’s history, their movement was marked by the impact of the oil crisis on guest workers, by French xenophobia, and by racist European immigration laws. Yet, “making and crossing borders has always been one of the ways in which societies are built,” as a spokesperson for the paperless put it, and so these people refuse “to return to the shadows” or to cave in to the new liberals’ adoption of colonialism. While capital may circulate freely, nationals of poor countries may not.

In Stanley-Becker’s “Epilogue” it all adds up to a verdict on Schengen’s role in Europe’s transformation into a common market and a site of human(istic) integration. The downside was a lack of model for transitioning into this “reunified Europe” within “the setting of globalization.” Open borders within Schengen turned into boundaries of exclusion surrounding the territory as “internal European freedom meant fortifying . . . external borders.” With the mass migration in 2015—about 13,000 into Germany every day—internal border control, which had been meant to disappear, only increased and deepened Schengen’s internal division. It was a backlash to free movement, and soon the borderless status was further compromised—first by Brexit, then by Covid—until internal borders literally got resurrected and controlled, if only indirectly and as an exception. Schengen “isn’t dead but broken” was the sense within the European Council, to which Stanley-Becker rightfully adds that there “was never a Europe without borders . . . Nor was it meant to be otherwise by the treatymakers.”

Rarely has the complexity of Europe’s recent border issues, and its mix of national and transnational inclinations, been as carefully documented as in Stanley-Becker’s book, from its front cover to its countless notes. Its source material contains dilemmas of such phenomenological importance that one would want to see them discussed beyond continental boundaries. They are food for rethinking borders (as John. C. Welchman called his 1996 anthology), and the outcome may well exceed the borders of both Europe and Europe without Borders.

Click below to purchase this book through Bookshop and support your local independent bookstore:

Rain Taxi Online Edition Winter 2026 | © Rain Taxi, Inc. 2026