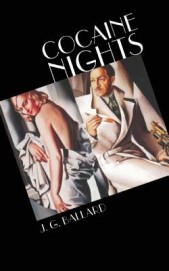

J. G. Ballard

J. G. Ballard

Counterpoint ($23)

by F. Caso

This novel, Ballard's latest, is at once a traditional mystery, an exploration in manipulation, and an edgy comment on the modern notion of utopia. The narrator, Charles Prentice, is a travel writer who has come to the Spanish coastal community of Estrella de Mar to clear his younger brother, Frank, of the murder of five people by arson. Despite Frank's being the well-liked manager of a place called the Club Nautico, no one seems to be rushing to his defense—probably because he has confessed and evidence of the crime was discovered in his car. Yet Charles is convinced of Frank's innocence and sets out to prove it as best he can.

What Charles soon realizes is that the citizenry of Estrella de Mar, most of whom are British expatriates, comprise as closed a society as anything ever imagined by Agatha Christie. Charles himself all but admits this when he observes, "In many ways Estrella de Mar was the halcyon county-town of England of the mythical 1930s, brought back to life and moved south into the sun." To this update of a classic mystery scenario, a contemporary patina is applied: drugs, pornography, burglary, and random mayhem, all of which serve as counterpoint to the bucolic setting.

As Charles comes to make the acquaintance of a number of the locals and a somewhat cerebral police captain—a role reversal that further modernizes the story—his perspective undergoes a transformation. For one thing, his early assumptions about the victims are entirely altered. This attempt at misdirection may feel clumsy and needless to the reader, who by dint of sticking with the story is not only willing to accept a degree of manipulation, but also willing to concede that things are not as they appear. Charles, though, is not the story's reader but its narrator, and despite his worldliness and initial skepticism, remains a gullible character.

Charles's gullibility is daily informed by his associations within the community and none more so than with Bobby Crawford, Club Nautico's tennis pro and Estrella de Mar's resident sociopath. The Oswald Mosley of this "England of the mythical 1930s," he serves as de facto social director and has lifted the sleepy village out of its torpor by applying his warped philosophy. Crime, he contends, has replaced politics and religion as the motivating factor in people's lives, and in Estrella de Mar, improbable as it seems, this is true. Now Crawford seeks to work his devious magic on an even more isolated place?a planned community called Residencia Coastasol—and he enlists Charles to serve as that community's sports club manager, an obvious replacement for Frank.

Charles becomes so enraptured by his duties that his criminal investigation is placed on the back burner. Indeed, he never really does solve the crime; it is solved for him, and the solution also harks back to Christie. The difference is the seductiveness of Crawford's ideology, which though seemingly postmodern contains a neofascist outlook that seeks to overturn other neofascist outlooks, such as the gated community. In typical Ballard fashion, a lesson of recent history is reiterated: wherever passivity gives way to moral ambiguity (or vice versa) something wicked will always come your way. What makes Cocaine Nights so appealing is that lurking behind the obvious lesson is a process of proselytization which the reader cannot ignore.

Click here to purchase this book at your local independent bookstore

Rain Taxi Print Edition, Vol.3 No. 2, Summer (#10) | © Rain Taxi, Inc. 1998