INTERVIEWS

The Ethos of Irony: An Interview with Lee Konstantinou

Lee Konstantinou’s new book approaches postwar literature, politics, culture, and counterculture through the lens of the ironic worldview, pioneered by hipsters, punks, believers, and the cool alike.

Interviewed by Dylan Hicks

The Nightboat Interviews

In eight interviews featuring authors published by Nightboat Books, Andy Fitch offers a comprehensive oral history of the diverse output of this decade old press.

Paula Cisewski • Juliet Patterson

George Albon • Michael Heller

Douglas A. Martin • Martha Ronk

Lytton Smith • Jonathan Weinert

Interviewing the Interviewer: A Conversation with Andy Fitch

To conclude our special section of Nightboat Interviews, we turn the spotlight on interviewer Andy Fitch to find out what drives him toward oral history projects. Interviewed by Caleb Beckwith

My Year Zero: An Interview with Rachel Gold

Enter the world of Rachel Gold's latest novel, which tackles the subjects of mental health, dating, making mistakes, being a young artist, and writing your own story. Interviewed by Steph Burt

COMICS REVIEWS:

Paper Girls, Volume 1

Brian K. Vaughn & Cliff Chiang

Strange goings on in a Cleveland suburb capture the attention of four paper delivery girls in this riveting graphic novel. Reviewed by Amelia Basol

ART REVIEWS

Matthias Buchinger: "The Greatest German Living"

Ricky Jay

Esteemed collector and magician Ricky Jay chronicles his obsession with the Little Man of Nuremberg, illustrated profusely with ornamental and wildly detailed micrographic works. Reviewed by Jeff Alford

FROM THE ARCHIVES

Broken Hierarchies: Poems 1952-2012

Geoffrey Hill

With the recent passing of Hill, whom many consider Britain’s finest poet, we bring this review of his selected poems online to celebrate his work. Reviewed by Adam Tavel

Chapbook Reviews

Black Movie

Danez Smith

Smith’s Black Movie is a cinematic tour-de-force that lets poetry vie with film for which medium can most effectively articulate the experience of Black America. Reviewed by Mary Austin Speaker

POETRY REVIEWS

Firewood and Ashes: New and Selected Poems by Ben Howard

Geis by Caitríona O'Reilly

Two collections of poems take on Ireland—one by Iowan Ben Howard, obsessed with the Green Isle, and the other by Irish poet O’Reilly, whose work is influenced by American poets. Reviewed by M. G. Stephens

Ventriloquy

Athena Kildegaard

Kildegaard’s latest volume of poems expand out from the garden to saints, divination, and ultimately to the universe. Reviewed by Heidi Czerwiec

Night Sky with Exit Wounds

Ocean Vuong

With an expert blend of the tender and the destructive, Vuong shows himself to be a master of the lyric moment. Reviewed by J.G. McClure

Histories of the Future Perfect

Ellen Kombiyil

Kombiyil uses boundaries as launch pads to careen from one galactic experience to the other, occasionally returning to the ground. Reviewed by Samantak Bhadra

Orphans

Joan Cusack Handler

This heartfelt collection of poems is an extended elegy to Joan Cusack Handler’s parents, who were Catholic immigrants from Ireland. Reviewed by James Naiden

Justice

Tomaž Šalamun

Šalamun’s posthumous collection is drawn from unpublished works and other collections, showing his seminal humor and fearlessness. Reviewed by John Bradley

Literature for Nonhumans

Gabriel Gudding

Gudding offers a “zoopoetics” that explores an empire defined by agri-industry and the slaughterhouse. Reviewed by Garin Cycholl

Extracting the Stone of Madness: Poems 1962 – 1972

Alejandra Pizarnik

This collection of poems by a powerful Argentinian voice peels back the skin of darkness to reveal an exploration of death, the wonders of childhood, and the heavy chains of imagination. Reviewed by George Kalamaras

FICTION REVIEWS

My Escapee

Corinna Vallianatos

The women who populate the stories in this prize-winning collection are bound together by a common desire to escape. Reviewed by Shane Joaquin Jimenez

Kuntalini

Tamara Faith Berger

Number 7 in the Unlimited New Lover series, Kuntalini follows erotic adventures in yoga class. Reviewed by Corwin Ericson

Eleven Hours

Pamela Erens

In her latest novel, Erens unpacks the fearful anticipations of becoming a mother and the painful process of losing one. Reviewed by Lori Feathers

My Name is Lucy Barton

Elizabeth Strout

Strout touches on themes of family and memory, poverty and superiority, loneliness and identity, providing a down-to-earth reflection on real life grace, searching, and the irreversibility of life. Reviewed by Emily Myers

We Could Be Beautiful

Swan Huntley

Huntley spins a spellbinding novel that explores wealth, trust, and the tumultuous nature of familial relationships. Reviewed by Rebecca Clark

Cities I’ve Never Lived In

Sara Majka

Majka’s debut novel follows the narrator, a women re-evaluating her life after a divorce, in a dream-like prose that blurs the line between memory and fact. Reviewed by Montana Mosby

YA FICTION REVIEWS

Lady Midnight

Cassandra Clare

In the first Shadowhunters novel, Clare engages with an enthralling plot, witty humor, romance, mystery, and plot twists that will have the reader gasping out loud. Reviewed by Jessica Port

NONFICTION REVIEWS

Germany: A Science Fiction

Laurence A. Rickels

Rickels traces the resurgence of German Romanticism in postwar Californian SF writing, as evidenced by Heinlein, Pynchon, and Dick. Reviewed by Andrew Marzoni

Real Artists Have Day Jobs (And Other Awesome Things They Don’t Teach You in School)

Sara Benincasa

Comedian Benincasa’s new book offers 52 chapters with life advice as told through deeply personal narratives. Reviewed by Christian Corpora

You Are A Complete Disappointment: A Triumphant Memoir of Failed Expectations

Mike Edison

Edison's humorous memoir unfolds into a heart-wrenching narrative of the author’s journey to make peace with his childhood, forgive his father, and find worth within himself. Reviewed by Bridget Simpson

We Believe the Children: A Moral Panic in the 1980s

Richard Beck

Beck writes about the Satanic Panic of the 1980s and its outlandish tales of child abuse, many of which were linked to accounts of bizarre devil-worshipping rituals. Reviewed by Spencer Dew

Six Capitals, or Can Accountants Save the Planet?

Jane Gleeson-White

Gleeson-White’s new book reports on cutting edge ideas in accounting with a keen and strongly critical eye. Reviewed by Robert M Keefe

Farthest Field: An Indian Story of the Second World War

Raghu Karnad

Karnad’s astonishing history casts the Indians who served the British Empire in Iraq during World War II in a prestigious role. Reviewed by Mukund Belliappa

Every Song Ever

Ben Ratliff

Ratliff’s book is a series of graceful music-appreciation essays designed for listeners evolving into a species inundated with thousands of kinds of music across culture, region, and history. Reviewed by Dylan Hicks

Satellites in the High Country: Searching for the Wild in the Age of Man

Jason Mark

Journalist and back country explorer Jason Mark argues that not only is the wild relevant, we need it now more than ever. Reviewed by Eliza Murphy

Pure Act: The Uncommon Life of Robert Lax

Michael N. McGregor

Inspiring and thought-provoking, this biography follows the unconventional life of an experimental poet who pursued life, faith, and art with authenticity. Reviewed by Linda Lappin

A Mother’s Reckoning: Living in the Aftermath of Tragedy

Sue Klebold

Klebold’s book is a sometimes obsessive investigation into the suicidal depression that her son Dylan hid from almost everyone—until he and his friend shot to death twelve students, a teacher, and themselves at Columbine High School. Reviewed by Jason Zencka

Surrealism, Science Fiction, and Comics

Edited by Gavin Parkinson

Gavin Parkinson is on a mission is to establish academic scholarship on Surrealism’s link to science fiction and to comics. Reviewed by Laura Winton

Rain Taxi Online Edition Summer 2016 | © Rain Taxi, Inc. 2016

Sue Klebold

Sue Klebold

Islam is a religion of peace. You’ve heard this idea before, and you’ve probably heard it said exactly like that. The reason these words are so familiar in the cultural conversation is because they so often need repeating in the face of bigotry; too often, Islam finds itself in the crosshairs of xenophobic scapegoating. More than any other group in 21st-century America, ordinary Muslim Americans get characterized by the terrible acts of extremists who inhabit their ideology.

Islam is a religion of peace. You’ve heard this idea before, and you’ve probably heard it said exactly like that. The reason these words are so familiar in the cultural conversation is because they so often need repeating in the face of bigotry; too often, Islam finds itself in the crosshairs of xenophobic scapegoating. More than any other group in 21st-century America, ordinary Muslim Americans get characterized by the terrible acts of extremists who inhabit their ideology. Scandinavia isn’t that big. Its defining feature might be that it’s a Separate Entity, in terms of its geography, culture, and presence on the global political stage. They speak their own languages, three of the four countries have their own currency, and they’re not even that popular of tourist destinations, when compared to locales throughout the rest of Europe and the world. But to Americans, particularly the ones making decisions about how the country is run, Scandinavia has a strange theoretical presence as either a utopia or a moral worst-case scenario.

Scandinavia isn’t that big. Its defining feature might be that it’s a Separate Entity, in terms of its geography, culture, and presence on the global political stage. They speak their own languages, three of the four countries have their own currency, and they’re not even that popular of tourist destinations, when compared to locales throughout the rest of Europe and the world. But to Americans, particularly the ones making decisions about how the country is run, Scandinavia has a strange theoretical presence as either a utopia or a moral worst-case scenario.

There is nothing you know as much about as your own body. To say you “know about it” is actually too much distance between you and it; we are our bodies, no matter how separate or at odds with them we sometimes feel. It’s interesting, then, how the body remains one of the great puzzles in all of human thought and science. Medicine, theology, literature, biology, sociology, even math: there are people in every field who have made a lifetime out of just trying to figure out what in the world we actually are, how we’re put together, and why. Think about it: isn’t this just a complicated version of staring at a mirror?

There is nothing you know as much about as your own body. To say you “know about it” is actually too much distance between you and it; we are our bodies, no matter how separate or at odds with them we sometimes feel. It’s interesting, then, how the body remains one of the great puzzles in all of human thought and science. Medicine, theology, literature, biology, sociology, even math: there are people in every field who have made a lifetime out of just trying to figure out what in the world we actually are, how we’re put together, and why. Think about it: isn’t this just a complicated version of staring at a mirror?

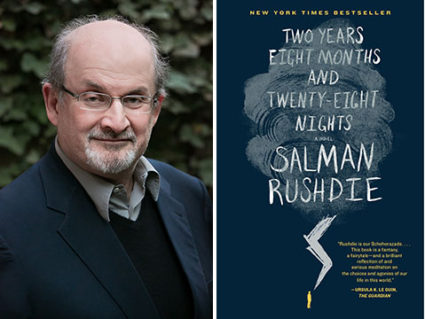

After writing his memoir and a children’s novel, Two Years Eight Months and Twenty-Eight Nights (less precisely 1001 nights) is Rushdie’s first adult novel in 7 years. Inspired by ancient, traditional “wonder tales” of the East, yet rooted in the concerns of the present, Rushdie’s novel blends history, mythology, and a timeless love story into a tale about the way we live now—an age of unreason. Satirical and bawdy, full of cunning and folly, rivalries and betrayals, kismet and karma, rapture and redemption, this story is quintessential Rushdie, a perfect mix of clever and fun, provocative and brilliant.

After writing his memoir and a children’s novel, Two Years Eight Months and Twenty-Eight Nights (less precisely 1001 nights) is Rushdie’s first adult novel in 7 years. Inspired by ancient, traditional “wonder tales” of the East, yet rooted in the concerns of the present, Rushdie’s novel blends history, mythology, and a timeless love story into a tale about the way we live now—an age of unreason. Satirical and bawdy, full of cunning and folly, rivalries and betrayals, kismet and karma, rapture and redemption, this story is quintessential Rushdie, a perfect mix of clever and fun, provocative and brilliant.