Sarah Evenson is a Minneapolis-based illustrator with a BFA in book arts from the Minneapolis College of Art and Design. In addition to Rain Taxi, her clients include Hallmark, Treat and Company, and Coffee House Press.

Sarah Evenson is a Minneapolis-based illustrator with a BFA in book arts from the Minneapolis College of Art and Design. In addition to Rain Taxi, her clients include Hallmark, Treat and Company, and Coffee House Press.

Instagram: @saltysweetsarah

Website: sarah-evenson.com

Uncategorized

Volume 21, Number 3, Fall 2016 (#83)

To purchase issue #83 using Paypal, click here.

[goal id="24811"]

INTERVIEWS

Kao Kalia Yang: Them Thoughts, Always Them Thoughts | interviewed by Scott F. Parker

Holly J. Hughes: A Quiet Letter to the World | interviewed by Mike Dillon

FEATURES

Daniel Berrigan: Writer | by Mike Dillon

Thomas Bernhard: The Limitless Capacity for Human Suffering | by Scott Bryan Wilson

Chapbooks In Review

Conditions/Conditioning | TC Tolbert & Jen Hofer | by MC Hyland

Collateral | Simone John | by Mary Austin Speaker

Enigmas | Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz | by Paula Cisewski

Lorine Niedecker’s Century 1903–2003 | Jenny Penberthy | by Mary Austin Speaker

Plus:

NONFICTION REVIEWS

The Whole Harmonium: The Life of Wallace Stevens | Paul Mariani | by Dobby Gibson

In Walt We Trust: How a Queer Socialist Poet Can Save America From Itself | John Marsh | by George Longenecker

At The Existentialist Café: Freedom, Being, and Apricot Cocktails | Sarah Blakewell | by John Toren

The Last of the Light: About Twilight | Peter Davidson | by Garin Cycholl

Oneida: From Free Love Utopia to the Well-Set Table | Ellen Wayland-Smith | by Spencer Dew

Strangers Drowning: Grappling with Impossible Idealism, Drastic Choices, and the Overpowering Urge to Help | Larissa MacFarquhar | by Marisa Januzzi

Lunch With A Bigot | Amitava Kumar | by Alex Brubaker

Pinpoint: How GPS is Changing Technology, Culture, and Our Minds | Greg Milner | by Ryder W. Miller

What Kind of Creatures Are We? | Noam Chomsky | by Trevor Quirk

FICTION REVIEWS

Square Wave | Mark de Silva | by Darren Huang

Natural Wonders | Angela Woodward | by Natanya Ann Pulley

Chicago Heat | Clarence Major | by Tyrone Williams

The Birds of Opulence | Crystal Wilkinson | by Kimberly Burwick

Violent Outbursts | Thaddeus Rutkowski | by Janusz Zalewski

Mongrels | Stephen Graham Jones | by Callum Angus

One Hundred Twenty-One Days | Michèle Audin | by Richard Henry

Paraíso | Gordon Chaplin | by Ilena Meyer

Sudden Death | Álvaro Enrigue | by Matt Pincus

I’m Thinking of Ending Things | Iain Reid | by Cynthia C. Scott

Beatrice | Stephen Dixon | by Caleb Bouchard

Bardo or Not Bardo | Antoine Volodine | by MH Rowe

POETRY REVIEWS

Walking Woman with the Tambourine | Janine Pommy Vega | by Margaret Randall

The White Stones | J. H. Prynne | by Patrick James Dunagan

Forest Primeval | Vievee Francis | by Kevin Holton

Dear, Sincerely | David Hernandez | by Allison Campbell

The Bridge | Mary Austin Speaker | by Annmarie Delfino

Memory Cards: The Thomas Traherne Series | Susan M. Schultz | by Greg Bem

Why Happiness Makes Me Nervous | Liza Charlesworth | by Kaylee Via

Old Ballerina Club | Sharon Olinka | by Dean Kostos

Odd Beauty, Strange Fruit | Susan Swartwout | by Laura Winton

Bright Dead Things | Ada Limón | by Abigail Williams

Demimonde | Kierstin Bridger | by Liz Walker

COMICS & THE ART REVIEWS

Blueprint for Counter Education | Maurice Stein and Larry Miller | by Richard Kostelanetz

Art & Beauty Magazine, Numbers 1, 2, & 3 | R. Crumb | by John Eisler

To purchase issue #83 using Paypal, click here.

Rain Taxi Print Edition, Vol. 21 No. 3, Fall 2016 (#83) | © Rain Taxi, Inc. 2016

Dream Closet: Meditations on Childhood Space

Edited by Matthew Burgess

Edited by Matthew Burgess

Secretary Press ($28.99)

by John Bradley

“I hid in closets, behind doors, and under tables,” writes Matthew Burgess, editor of the fascinating anthology Dream Closet, “meditations on childhood space.” “I crawled into the cabinet under the sink,” he continues, “and climbed trees to find hidden perches.” He loved books “filled with small spaces that doubled as portals to other worlds.” No wonder he would one day edit an anthology filled with personal tales of such portals.

Inspired by the phrase “dream closet” from Denton Welch’s novel In Youth Is Pleasure, where a child transforms a bathroom into an imaginative space, Burgess asked a variety of artists—writers, painters, and photographers—to interpret this concept of a child’s private space. The results (six chapters containing twenty-five prose pieces, twenty-four poems, and thirteen works of art) are richly varied and engaging, attesting, in varying ways, to the importance of both hiding and becoming “unhidden.”

For many of the artists, hiding in a private space was partly playing a game and partly following an instinct. A lovely photograph by Brett Bell called “Henry” captures both aspects. The image shows a young child lying on a leaf-strewn lawn with his head inserted in a cardboard box labelled “HUNTINGTON HOME.” The child no doubt believes he is hidden from view, as he cannot see who might be watching him from his new “home.” This basic premise of not being seen and therefore feeling safe runs through many of the pieces here, such as Ron Padgett’s—who, at fourteen, built a private crawl space in the garage, complete with a magazine from the Soviet Union and a short-wave radio to hear the BBC. The immediate world is shut out and the larger world let in.

In his introduction to the anthology, Burgess shows us the simplicity and complexity of this urge for a private space. He recounts how Vladimir Nabokov tells, in Speak, Memory, of crawling into a “tunnel” between furniture and a wall: “I lingered a little to listen to the singing in my ears—that lonesome vibration so familiar to boys in dusty hiding places, and then—in a burst of delicious panic, on rapidly thudding hands and knees I would reach the tunnel’s far end, push its cushions away, and be welcomed by a mesh of sunshine.” As lovely as this description is, Nabokov makes one mistake—claiming that the experience is limited to boys. Virginia Woolf recalls in “A Sketch of the Past” how as a young girl in the nursery, she imagined herself “lying in a grape and seeing through a film of semi-transparent yellow.” Many female voices in Dream Closet further demonstrate that this need for seclusion transcends gender. Marie Howe writes of going to the basement as a child with eight siblings to create “a town” made out of “boxes and blankets and overturned chairs.” One of the children would act as the Town Crier, calling out the hours: “Ten o’clock and all is well.” Melissa Febos, in “The Rule of Burned Things,” hid in a closet and burned scraps of paper and pillow stuffing in a Mason jar: “Spark and flash of becoming, sharp scent of shape shift.” Her secret place gives her the power to create and destroy.

One of the delights of this anthology is the creativity of the contributors in how they locate that private place. For Christina Olivares, in “At Twelve,” that space was found when diving into a pool for a dropped penny: “We push toward a silence that would keep us safe.” In a photograph by Libby Pratt, we see illuminated pages of a book held open by two fingers. The very act of reading becomes that safe place. In a photograph, perhaps the most stunning of all the artwork, entitled “James at Dusk,” by Michi Jigarjian, we see a baby illumined by the sun prancing inside a sheer curtain, both hidden and yet visible, the joy of the act palpable. Only one writer in the anthology finds the “dream closet” to be disturbing. Julian Talamantez Brolaski, in “The Bad Dream Closet: Amphibian Enterprize,” describes a reoccurring nightmare where he is stuck in a well with a monster who is “Literally holding my breath in its claws.” Though nothing happens in the well, the image itself is terrifying for both Brolaski and the reader.

For some writers, the concept of hiding and being revealed has to do with altering his or her physical appearance. Jeffrey Conway, in “My Childhood in Drag: Five Photos,” offers no explanation, just vivid descriptions of how he appears in each photograph. For example, one Halloween when he’s in sixth grade, he dresses as his mother:

I wear her poofy brunette wig, coffee-colored nylons, her short read and blue print polyester dress, her white cotton sweater over my shoulders (the sleeves dangle at my sides) with only the top button fastened. I have stuffed the dress so that my “breasts” are huge. I wear orange lipstick. I can remember the flash of dread I felt when my dad said, just before I dashed out the front door, “What will your football teammates say when they see you?”

Perhaps they wouldn’t recognize him? Or would they see him for the first time? “We hide ourselves in order to become unhidden to ourselves,” observes Matthew Burgess in his introduction. In the act of donning a costume, Conway becomes “unhidden” to himself, his family, and the world.

By the end of this anthology, the link between hiding and transforming becomes clear. In “The Imaginal Moi & the Clubhouse,” James Lecesne tells of hiding family objects, such as his mother’s butterfly pin, in his clubhouse. When he goes back to retrieve the pin, it’s gone. He concludes his story with this realization:

Years later, when I learned how butterflies actually get made, I couldn’t help thinking about my clubhouse and that long lost butterfly pin. Once inside the chrysalis, the caterpillar slowly disintegrates, dissolves into a soupy mess and disappears. All that remains of him is something called the imaginal cells; out of these very elemental and essential cells, a butterfly is born.

The child cannot understand the profound implications of retreating into that private, enclosed world. Only the adult looking back can begin to unravel the layers of meaning of entering the “dream closet.” The fifty-four artists of this unusual anthology, as well as the editor, serve as trustworthy guides to these transformational “portals to other worlds.”

Rain Taxi Online Edition Fall 2016 | © Rain Taxi, Inc. 2016

To Think of Her Writing Awash in Light

Linda Russo

Linda Russo

Subito Press ($18)

by Catherine Rockwood

In four innovative essays, Linda Russo celebrates five female authors whose lives span the interval from the Romantic period to the present day. In the first essay, on Dorothy Wordsworth, Russo traces a causal connection between the author’s daily walks and her ability to think in ways that proved useful to her famous brother. She also introduces the feminist practice of “talk[ing] back to literary history,” catalyzed here by evidence of Dorothy’s erasure from William’s compositional process. Russo’s secondhand copy of Dorothy’s Journals came, she tells us, from the library of a women’s college, and its trenchant marginalia “tracks Dorothy’s words in William’s poems and traces William’s treads through Dorothy’s journals.” The high quality of that sentence, which uses parallel structure to set Dorothy’s lightfoot “words” against William’s implicitly stick-cracking “treads,” is representative of the book overall.

A lengthy second essay on Dickinson shows how “E.D.” is rendered present and active by Russo’s tenacious imagination and the books she packs along on delighted but undeceived visits to Dickinson’s desk (at Harvard University) and to the Dickinson homestead in Amherst. The essay begins in Dickinson’s room itself, where Russo gazes through its windows: “Today the sky is a luminous slate,” she writes, showing us a bright blank that she herself must trace meaning on, and does.

With Hettie Jones, the third essay shifts into the twentieth century. Jones’s 1990 memoir, How I Became Hettie Jones, details her work as unofficial amanuensis to her then-husband LeRoi Jones, later known as Amiri Baraka. In response, Russo writes a crackling experimental dialogue laying bare the absurd systems of thought that designated LeRoi Jones a poet and his wife “an important component in the production of poetry.” It’s a virtuoso performance, both angry and artful. The fourth essay, on contemporary poets Joanne Kyger and Anne Waldman, begins at Kyger’s tea-table, among conversation. Here we come into the present, where Waldman’s recently completed feminist epic, The Iovis Trilogy, can be discussed between friends. If these friends are also influencers, whose voices sometimes over-write the author’s own, it is by now a small matter; if we want to dissent, Linda Russo has shown us how we can thoughtfully talk back, even to a history of her own choosing.

Click here to purchase this book at your local independent bookstore

Rain Taxi Online Edition Fall 2016 | © Rain Taxi, Inc. 2016

A Cage in Search of a Bird

Florence Noiville

Florence Noiville

Translated by Teresa Lavender Fagan

Seagull Books ($21)

by Jeff Alford

A fragile mind can be afflicted with an obsession like a stroke. In a snap, a person can be consumed with “the delusional illusion of being loved”: some lingering eye contact or an innocent inquiry from a stranger can swell from meaningless happenstance into something emotional, erotic, and far beyond logic’s reach. Obsessed fans, jealous friends, and ex-lovers can all unspool into a debilitating romantic fanatacism. French psychiatrist Gaёtan Gatian de Clérambault (1872-1934) was particularly interested in (and almost, ironically, obsessed by) “cases of romantic delusion” and named this affliction of erotomania after himself.

Florence Noiville’s A Cage in Search of A Bird investigates de Clérambault Syndrome by wrapping its peculiarities in the mantle of a psychological thriller. When television journalist Laura Wilmote sees her old friend and current co-worker “C” in their office one morning dressed entirely in a matching outfit, Laura “understood that something was wrong.” “Look! I’m dressed as you!” C exclaims, sounding in Laura’s mind “like a warning.” Expectedly, C’s infatuation grows to disturbing heights as Noiville’s cinematic novella unfurls.

C begins sending impassioned nightly emails to Laura recalling their teenage years, before they lost touch, when they would read Sappho together and explore New Wave Cinema. Laura grows increasingly uncomfortable with this new emotional intimacy and upon learning about de Clérambault syndrome, attempts to analyze C from a safe distance—all while channeling her obsession into something that could be used for a forthcoming TV feature, or, with a wink from Noiville, a future novel.

Noiville, a staff writer for Le Monde, has playful similarities to Laura and this self-referential game ultimately defines A Cage in Search of a Bird: the boundaries between narrator and author blur into a woozy unreliability and the novel twitches with the power of a mentally unstable confession.

De Clérambault believed that the only way to end a loop of erotomania is for one of its nodes to die: “either they destroy themselves . . . or they destroy the object.” This fatalism might be acceptable coming from an early-twentieth century psychiatrist devoted to this caliber of obsession, but seems unnecessarily excessive to utilize as a literary device. As Laura’s emotional fortitude breaks down and as C’s advances more effectively integrate her into Laura’s life, A Cage in Search of a Bird begins to fray. A perfunctory finale weakens this short novel, although it remains a fascinating, thrilling diversion.

Click here to purchase this book at your local independent bookstore

Rain Taxi Online Edition Fall 2016 | © Rain Taxi, Inc. 2016

CLOSE READING: An Interview with Derek Walcott

by Michael Swingen

by Michael Swingen

There was a predawn chill in the morning wind as I waited in the downtown port of Fort-de-France to board the ferry for St. Lucia. It was Christmas time last year, and in the boarding station St. Lucians chatted with holiday cheer as they waited for the return passage home. They had traveled across the blue channel to Martinique, one of the neighboring French islands, to buy Christmas presents to bring home to their families. Martinique has an Antillean reputation for sophistication, and St. Lucians carried with them bags full of chocolates in pink boxes, transparent cases of artisanal pastries, and wine bottles with elaborate crests on their labels. I, too, was going home for the holidays. It was cheaper to fly out of St. Lucia than Martinique, where I was teaching English in a high school for the year, and the boarding station where I waited with the St. Lucians overlooked the bay that led to the blue channel that divided the two islands.

It was late at night when I reached my Bed & Breakfast. Despite the midnight hour, my host Wendy was electric when she opened the front door, lively as palm fronds applauding themselves in the wind. She laughed and sometimes clapped as she gave me a tour of her small gabled house on the quiet outskirts of the capital. She had just self-published a children’s novel, she told me, which she displayed on the side table next to the orange sofa, where she sat across from me in the living room. I asked her if she had ever read Derek Walcott, who was also from St. Lucia. She was friends, she laughed, with Mr. Walcott’s companion Sigrid Nama. Wendy got up from the sofa, headed for her old rotary dial phone next to her computer, and called up Sigrid. She explained that there was a young man here who would like to meet Mr. Walcott. Sigrid told Wendy that I should come by their house in two weeks. By the way, I heard Wendy say, would Mr. Walcott be interested in conducting an interview for Rain Taxi Review of Books?

During the holidays, while all those blizzards were raging across the East Coast and burying New York and Boston in snow, I researched and prepared for the interview with a ferocious intensity, predicated less upon scrupulousness and more on animal terror. After all, after six decades of transforming the Caribbean world into the permanence of poetry, Derek Walcott, a Nobel Laureate, is one of the lions of world literature. In the first decades of his career, a large part of Walcott’s ambition was to bring his native St. Lucia into literature for the first time. Many of his early poems aim to show that the Caribbean—its people and landscape and history—belongs in English poetry no less than England itself. Omeros, Walcott’s retelling of the Iliad on the shores of his native St. Lucia, for example, is taught in many college classrooms and has become a staple of postcolonial literature. But for Walcott the oppositions between empire and province—and, inevitably, between black and white—can never be easily reduced to simple postcolonial dictums that declare an artist deploy her craft to strike back against ex-imperial masters. “It is the [English] language which is the empire,” Walcott has written, “and great poets are not its vassals but its princes.” From this private sensibility evolves an oeuvre—seventeen poetry collections, nine volumes of drama, and a book of essays—of a poetic imagination unparalleled in the almost magical gift of rendering the world transformed by the power and grace of language. How to prepare for an interview, then, with a writer of this caliber?

And so I devoured all the Walcott I hadn’t already read, holed up in my parents’ basement like a hibernating mole. I also read all the interviews Walcott had done in the past. I composed immaculately crafted questions dredged from the deepest abysses of literary theory and my own personal boreholes of confusion. Earlier that year, I had completed a master’s program with a thesis on Hart Crane and Stéphane Mallarmé, and I craved to know what Walcott thought of the 20th-century American poet, whom Walcott had written about in his youth. Finally, I sculpted the interview questions, squaring and settling their syntax and turns of phrase (I reproduce them in an appendix to the conversation for those who wish to see how well I succeeded).

When I returned to St. Lucia I did not stay with Wendy again but found rather a quiet room in a fishing village called Gros Islet on the northwestern side of the island. I stayed there for two days before I met Walcott, who lived not far from the village. From the terrace of my room I stooped on the scalloped balcony and watched shirtless boys ride horses without reins or saddles along the bright beaches. The boys would hunch and grip the wispy manes of the horses whinnying, and when either the boys or the horses grew tired, they would ride into the translucent shallows of the turquoise water. Boys riding horses would never happen in Martinique; something about the French-inflected island would not permit it. Like siblings, the islands were different.

When I knocked on Mr. Walcott’s and Sigrid Nama’s front door, I wore a navy button-down dress shirt with a gold pin dot tie, both of which I had dry cleaned before I left the United States. At the backside of his house, the Nobel Laureate and I sat under the verandah that looked out onto the sea and the sphynx-like Pigeon Island. Walcott’s robin’s egg blue t-shirt, which matched his swim trunks, had a breast pocket that sheathed two pens. I would later learn that he liked to have a writing utensil always handy in case he had to net any flights of fancy that dare flitter away. I kept my tie on for the entirety of the interview, but by the end both Derek and Sigrid teased me and requested that I take it off before we went to go eat dinner at the marina.

[The tape recorder is turned on while Walcott is asking me about where I come from.]

Michael Swingen: I’m from the Midwest, North Dakota, although no one knows where North Dakota is, so going to a place like Dartmouth was somewhat intimidating. Maybe you felt that, too.

Derek Walcott: Mhm.

MS: I remember reading this in one of your essays, that the first time you went to New York the “canyons of buildings” terrified you. I had similar feelings; the prestige of Dartmouth absolutely petrified me.

DW: So how long were you at Dartmouth?

MS: Two years, I did a master’s degree in comparative literature. I compared Hart Crane to Stéphane Mallarmé.

DW: Do you know French, too?

MS: I do. That’s why I’m in Martinique, because I studied French. I speak it pretty well.

DW: Continue talking in French.

MS: Vous voulez que je continue à parler en français ?

DW: Oui.

MS: Ah, parce que vous connaissez le français.

DW: Oui.

MS: A cause du créole alors.

DW: Voilà.

MS: Oui, c’est ça. Quand j’entends le créole en Sainte-Lucie, effectivement, je relève sur le français, donc quand on dit “merci” en créole on dit littéralement “merci, ”par exemple ! C’est passionnant.

DW: [to Sigrid] He’s talking French!

SN: I know, I heard that! You’re checking his French out?

DW: He’s showing off . . .

SN: [Laughs] Alright, I’ll let you two chat.

MS: Sure, thank you.

SN: Otherwise I’ll take over.

MS: Oh, that’s fine. Thank you for the wine. I appreciate it.

SN: You’re welcome.

DW: So where are you staying here?

MS: I’m staying in Gros Islet. Just another B&B.

SN: Yeah, which one?

MS: It’s called Beaches Inn. It’s right on the beach.

SN: The orange place?

MS: Yeah, it’s orange.

SN: It’s by the river outlet. Right?

MS: Yeah.

SN: “No dumping of refusal.” They had a sign there once: “No dumping of refusal.”

MS: [Laughs]. Of “refusal,” not “refuse.”

SN: It used to be owned by an Austrian-German guy. How is it? Is it okay?

MS: I like it. Honestly, I think I chose the wrong island. I like St. Lucia more than I like Martinique.

SN: Well, it’s a split personality. English and French, you know.

MS: Well, I don’t mean to generalize, but I feel that in Martinique, they suffer from Francophilia . . . their politesse oppresses them. They’re too snobbish. I’ve never seen the parties in Martinique that I’ve seen in St. Lucia.

SN: We have a good friend there: Patrick Chamoiseau. He only speaks French though.

MS: I haven’t read any of his work.

S: You’ll have to read Texaco in English.

MS: Oh, I’ve heard of this book!

DW: So you got a scholarship to Dartmouth?

MS: I did. Which was another reason it was so terrifying. They paid me to go, and that was just that much more pressure.

DW: What was it like physically? What did you have to do?

MS: It was two years, with trimesters, so there’s three quarters—fall, winter, spring—and each quarter you take three classes, and you have to be a teacher’s assistant, and then you have to do a research assistantship as well, and then at the same time you have to be doing your own research for your thesis.

DW: But you are a poet?

MS: Yeah, that’s always been the main goal. Learning French, going to grad school, it’s just putting tools on my utility belt. I grew up obsessed with T.S. Eliot, so I had it in my head that I had to do all this shit in order to entertain the idea of being a poet: I had to learn French, I had to go to grad school . . . all while not writing a lot of poetry . . . But now that I finally finished grad school I feel like I can actually go back to the source, to what it was all about.

DW: How long are you going to be staying?

MS: In Martinique?

DW: No, here.

MS: I’m here for two more days. But then I’m back in Martinique until June.

DW: Because that’s part of your job, right?

MS: Yeah. I start back up teaching in a week.

DW: Can you come back here on the 23rd?

MS: What’s happening the 23rd?

DW: Birthday. We go on a boat on the catamaran in Soufrière.

MS: What day is the 23rd?

DW: Saturday.

MS: I’d like to make that. I can make that.

DW: Because there will be some nice guys there. Young Italian poets. Italian women, too. Very nice people. About 40 of them. Come on the boat, definitely. Find out how you’ll do it, right? Ask Sigrid.

MS: I just have to take the ferry. It’s not difficult taking the ferry from Martinique to St. Lucia, it’s only an hour and a half. In American terms that’s, you know, like that [I snap my fingers]. I grew up traveling from North Dakota to Montana for ski trips. That was an 18-hour car ride.

DW: 18 hours?

MS: I’m as far east in North Dakota as you can get, it borders Minnesota. So all the way across North Dakota, and then all the way across Montana. 18-hour car ride for a weekend ski trip.

DW: You don’t mean 18 . . .

MS: Yes, 18! North Dakota and Montana are huge, you know. They’re huge states.

DW: So how many hours on the plane?

MS: Oh, maybe two or so? But 18 hours driving.

DW: You would take the car instead of a plane? Why? Money?

MS: Probably, but that’s just what my family did. I don’t know. Do you think I could read your poem “Hart Crane” out loud and then you could tell me what Hart Crane meant to you?

DW: I would hate that.

MS: Why?

DW: [Laughs] I don’t know.

MS: I just think it would be so cool to read poetry with you. Can I read “O Carib Isle!”?

DW: Is that a Crane poem?

MS: Yes.

DW: What’s the point of this?

MS: Um, the point of it is that when I was sixteen years old I found Hart Crane, and it blew my mind, it melted my brain out of my ears . . .

DW: How old were you?

MS: Sixteen.

DW: So you were astonished at the metaphors and stuff like that?

MS: Yeah, exactly. I still can’t believe the things he wrote. “In alternating bells have you not heard / All hours clapped dense into a single stride?” I mean shit like that, it’s absolutely insane. And I don’t remember how I found your work, but I’m pretty damn sure it had to do with Hart Crane. When I found you and read In a Green Night, I saw Hart Crane all over your poems. So that’s why I want to ask you how you found him, and what he meant to you.

DW: You know “To Brooklyn Bridge”?

MS: Of course, yeah.

DW: Let me hear how much you know.

DW: “How many dawns . . .”

MS: “How many dawns, chill from his rippling rest, / The seagulls wings shall dip and pivot him” . . . and then he . . . he says, “chained high”. . . over something something “Liberty,” with a capital L. Do you remember the full quatrain?

DW: I’m trying to remember the third line.

MS: [Gets book out] “How many dawns, chill from his rippling rest / The seagull’s wings shall dip and pivot him, / Shedding white rings of tumult . . .”

DW: Now tell me about that line. What does Crane see in that line?

MS: “Shedding white rings of tumult?” Um, what I honestly see, do you know how in cartoons when something is moving really fast, there’s lines going behind it?

DW: Yeah.

MS: Well, Crane is writing this line before cartoons like that probably existed, but I feel like he’s trying to articulate the motion of the seagull, and he’s describing—invisible to most people—wings of tumult as the seagull moves . . .

DW: White rings of tumult, not wings . . .

MS: White rings, I know, I know, as if the seagull’s leaving the bridge or coming back and the motion of his wings is shedding rings . . . [I try looking at the book]

DW: No, don’t look at it.

MS: Okay.

DW: Now you saw that at 16?

MS: Well, I think Crane helped me see it.

DW: What about “building high / Over the chained bay waters Liberty–”: Tell me about that line.

MS: That line has always confused me.

DW: “Building” what?

MS: White waters . . .

DW: No . . . “Shedding white rings of tumult,” “building high,” right? That’s a verb.

MS: Right. Oh, building. It’s probably the bridge.

DW: No, it’s not the bridge. It’s the statue.

MS: Oh, it’s the Statue of Liberty, hence “Liberty” at the end of the line. That’s incredible.

DW: Now, “building high” over the what?

MS: “The chained bay waters Liberty.”

DW: Why “chained”?

MS: Uh . . .

DW: You know Dylan Thomas?

MS: Sure.

DW: He has a line: “Though I sang in my chains like the sea.” What does that mean?

MS: What it makes me think of is Crane’s poem “The Broken Tower,” when he compares himself to the sexton, the one who actually rings the bell in the belfry, saying: “And I, its sexton slave” . . . it’s almost as if Crane is burdened by his immense creativity, that it was too much for him to handle. I think that’s maybe what both Thomas and Crane mean by “chained.”

DW: The image in Dylan Thomas is: “Though I sang in my chains like the sea . . .”

MS: I don’t understand “like the sea,” what does that mean?

DW: It’ll come to you miraculously when you look at it. You know how the waves do this? [He revolves his pointer finger in the figure of a circle] Those are chains.

MS: That is fantastic.

DW: “Building high over the chained bay waters,” you see it?

MS: I see it now, that’s incredible. Just that somebody could see that and articulate it.

DW: Right. So go back to the first stanza. Start it again. “How many dawns . . .”

MS: “How many dawns, chill from his rippling rest

The seagull’s wings shall dip and pivot him,

Shedding white rings of tumult, building high

Over the chained bay waters Liberty—“

DW: You know, I’ve taught this a lot, you notice how soft the beginning is in terms of vowels . . . Why is that?

MS: Because it’s dawn, and dawn is soft, it’s blurred . . . the phonetics are mimicking the scene they’re describing.

DW: You think you’re fuckin’ bright, don’t you?

MS: [Laughs] No . . .

DW: Because that’s right, that’s perfectly right.

MS: Well, that’s kind of what my thesis was about. I feel like a lot of Crane’s content, in his poetry, is interpreting the rhetorical figures that that content is written in . . . So for example the first couplet in White Buildings, from “Legend,” goes: “As silent as a mirror is believed / Realities plunge in silence by . . .” That couplet is shaped in the form of a rhetorical trope called chiasmus, a sentence where you have two parts and the second part repeats but inverts the first. So you have Ovid saying, “I flee who chases me, and chase who flees me”: The second part repeats the first but then flips it. In Crane’s couplet, “As silent as a mirror is believed / Realities plunge in silence by . . .,” the second line subtly mimics the first; so when he’s using this mirror-like rhetorical trope he’s not writing about love or war, he’s actually writing about mirrors, he’s writing about reflection. So it’s as if the content is interpreting its own rhetorical structure.

DW: What is the meaning of “believed” in the poem—what “believes”?

MS: Say again?

DW: Who is believing? What is believing?

MS: I’m not sure, what do you think?

DW: The poem is itself a mirror. The mirror is believed the way a poem is believed. It’s believed because it’s there.

MS: Right . . .that makes me think how at the same time, the poem admits the idea of narcissism. That first couplet, “As silent as a mirror is believed / Realities plunge in silence by . . . ”—it almost stages that moment when Narcissus is looking at his own reflection in the pond.

DW: You think it’s a pond or a page?

MS: I think [confused] . . . Well, he uses the word “plunge,” which suggests both pond and page.

DW: So who is looking?

MS: My opinion: the language itself. It refuses to be a reference for anything outside of itself.

DW: Okay, let’s begin again. “As silent as a mirror is believed . . .” That is staggering, isn’t it?

MS: Yeah, definitely.

DW: What’s staggering about it?

MS: Hmm . . . mirrors are supposed to be a faithful replication of what’s in them, right? But they’re always changing, they flip what’s in them . . . If you hold text up to a mirror, for example, it’s seen backwards, right? So “As silent as a mirror is believed . . .” I don’t know, what do you think?

DW: Let’s go down a bit more. “As silent as a mirror is believed . . .” Just the action in that is fantastic. We look and see what we see in a mirror, and we believe it. That’s important, the question of belief. The question is: Should we believe what we see in a mirror?

MS: Oh, right. Yeah, that’s fantastic.

DW: The second part of that is: “Realities plunge in silence by . . .” So what keeps multiplying images? The mirror, right? The thing that is believed is a reality.

MS: But it “plunges in silence by . . .” So is it plunging in the mirror?

DW: Yeah. One of the questions it asks is: Is the believer to be believed?

MS: Right.

DW: I look in the mirror. There’s me. What’s in the mirror is not real. So am I unreal? You see that?

MS: Yeah, I see that.

DW: Did you see that before?

MS: No, not before, no.

DW: You did in a way though.

MS: Crane’s poetry to me is unmediated language, it’s immediate, there’s no outside reference. I feel like for Crane to reach that level of language requires sacrifice, maybe almost death, which is why I thought the first couplet has Narcissus in it. After that opening couplet he writes: “I am not ready for repentance; / Nor to match regrets.”

DW: Those are the next lines?

MS: Yeah, that’s the third line: “I am not ready for repentance,” semicolon, “Nor to match regrets.” So it’s as if Crane’s desire is kind of suspended—I am not ready to repent, nor am I ready to match, to equal my sins.

DW: What does that have to do with the mirror?

MS: Okay, so after that he goes: “For the moth / Bends no more than the still / Imploring flame,” which is the figure of Icarus! So in the opening couplet you have Narcissus looking at his own reflection, which is vanity, and then Crane reveals the extreme ambition of Icarus, too . . .

DW: Let me ask you one general question, which is crucial: Do you believe that Crane’s belief in the poem was planned and charted, or did it come as inspiration?

MS: Inspiration, 100%.

DW: Hold on. But with its own logic?

MS: Yes, and that’s the key, that’s why Crane is the top of the top. That’s why he’s a real poet, like you. The poems develop their own internal system of logic.

DW: Since it deals with belief and surfaces, then it has to do with belief and poetry. You see that?

MS: Yeah, absolutely.

DW: How do you see it?

MS: It’s the first couplet again: Mirrors do reflect, so it’s as if they’re superficial, but it’s not a mirror actually, it’s a pool of water, and that has great depth under it.

DW: Well, I think the object is a mirror!

MS: But Crane is saying something is on the other side. That despite the fact that mirrors reflect, that they seem superficial, there is depth to them at the same time.

DW: Are you changing it from a mirror to a pool of water?

MS: I am, because I think that couplet evokes Narcissus, when he’s looking at himself . . .

DW: You’re bigger than that, these Greek evocations. That’s for undergraduate stuff, all these myths.

MS: [Laughs]

DW: I’m not saying that they’re not there . . . but I’m going to jump to a demonstration of Crane’s spectacular gift in metaphor: “O, like the lizard in the furious noon . . .” That’s hair raising, isn’t it?

MS: Yeah, it is. It is.

DW: The lizard is in the middle of “noon.”

MS: Oh, wow.

DW: Physically in the middle of “noon.” You with me?

MS: Yeah, I’m with you. I’ve never thought of that before.

DW: I’m not finished.

MS: [Laughs]

DW: Why “furious”? That’s Elizabethan, it’s Marlowe: “furious noon.” It comes from Tamburlaine.

MS: Crane was obsessed with the Elizabethans.

DW: “O, like the lizard in the furious noon, / That drops his legs and colors in the sun . . .” What we have is the desert . . . Crane goes out into the desert, and it’s high noon: O-O-N . . . Zero, Zero, N . . . Zero, Zero, the face of the sun, and when the sun is depicted at that time of day, it’s depicted with air around it, like . . .

MS: Like the corona . . .

DW: Exactly. It’s angry. It’s angry because it’s hot. So we go back . . . “O, like the lizard in the furious noon, / That drops his legs and colors in the sun . . .” I don’t think I have Crane here. You have Crane?

MS: Yeah, right here.

DW: You look for it.

MS: Is that in his Key West: An Island Sheaf?

DW: The Bridge. Look for, um . . . Do you have first lines?

MS: First lines?

DW: First lines . . . in the index in the back.

MS: Ah, ok . . . No, there’s no first lines . . .

DW: Yeah, I can see them. What’s that there?

MS: No, these are his letters. See if you can find it [hands book to Walcott]. Do you remember when you first found Crane what it was like for you?

DW: Oh, I was young . . . I was reading everything.

MS: Did you write a lot of poetry when you were in school?

DW: Yeah.

MS: I found that so difficult. To do schoolwork and write at the same time.

DW: Ok. Here we go.

MS: You found it?

DW: “O, like the lizard in the furious noon,

That drops his legs and colors in the sun,

—And laughs, pure serpent, Time itself, and moon

Of his own fate, I saw thy change begun!”

The lizard is supposed to lose his legs, right? And guess what happens?

MS: They change color?

DW: Not only color. He “drops his legs.”

MS: Ah, he sheds them. When a bird is about to attack a lizard, it sheds its tail as a decoy . . .

DW: What would physically happen if it lost its legs? What would the shape be?

MS: It’d be an O, wouldn’t it? Oh wow.

DW: Zero. Did you ever see that?

MS: No, never.

DW: There’s always more to see.

MS: It’s inexhaustible.

DW: This is why, in theory, he’s the greatest American poet at that point.

MS: I agree.

DW: So he sees the process of the lizard that he’s looking at dropping his legs because of high noon and becoming a what?

MS: I don’t know.

DW: No legs.

MS: A serpent!

DW: Brilliant. You get it.

MS: That’s incredible.

DW: That is a myth. An Indian myth right there.

MS: Mhm.

DW: So what’s he saying? I’m in the desert. I look down and see this creature lose its legs and tail and become “pure serpent.” But what does that zero do? That O? In terms of time?

MS: Well, zero represents infinity because there’s no beginning or end.

DW: Did he show you that?

MS: I don’t know who showed me that.

DW: “O, like the lizard in the furious noon,

That drops his legs and colors in the sun,

—And laughs, pure serpent, Time itself, and moon

Of his own fate, I saw thy change begun!”

Time itself is in the zero. It’s the symbol of time, of infinity. [He looks again at the book] Jesus Christ, he doesn’t stop . . .

MS: [Laughs]

DW: “And moon / Of his own fate.”

MS: There’s the circle again. It’s turned into the “moon.”

DW: The prophetic moon.

MS: It keeps transferring.

DW: Prophetic! And the phases of the moon are there: half moon, full moon, quarter moon . . .

MS: Wow.

DW: “I saw thy change begun!”

MS: Full moon, half moon, quarter moon, time passing . . .

DW: All the phases you will go through . . . When you read Crane, you come across Eliot and Pound. What do you do?

MS: What do you mean?

DW: Well, what does one do? Coming across Crane coming across Eliot and Pound?

MS: Well, Crane had so much trouble with Eliot. That was his most problematic influence, I think you could say. Eliot did not go down easy for him, like Whitman and Dickinson did. But I don’t know what I’d do when . . .

DW: In terms of poetic theory . . . contrasting the two of them.

MS: Well, Crane is always championing the positive affirmation. Crane is praise, and Eliot is melancholy, negativity, pessimism . . .

DW: No, but in terms of . . . that may be true, but in terms of the technique . . . what is there in Crane practically that is not there in Eliot?

MS: Meter, lots of iambs . . .

DW: Okay, if you stay on meter alone, what is the argument, on both sides?

MS: I don’t know, I’ve always had trouble with meter.

DW: Because you’re an American.

MS: I don’t know what it is.

DW: No, that’s what it is. It sounds forced to you because it’s not William Carlos Williams, it’s not free verse.

MS: Right, right. I remember in high school I had to go to my English teacher and stay after class and have her teach me how to scan lines. We’re not taught meter. We don’t have to talk about this because . . .

DW: Yes, we have to because it’s essential. In other words, the meter of Crane was wrong for Pound and Eliot. Am I correct?

MS: I think so, because they championed free verse.

DW: Wrong!

MS: No?

DW: What did they not champion?

MS: Anachronism, maybe. Did they find Crane anachronistic with his meter?

DW: What is that meter?

MS: Um. Blank verse. He did lots of blank verse.

DW: Right. Pentameter.

MS: But what did Eliot and Pound have against blank verse?

DW: Pound said, “To break the pentameter, that was the first heave.”

MS: What does he mean by that?

DW: The first thing we have to do is get rid of the pentameter. To ditch the pentameter. “That was the first heave.” So who was he talking about?

MS: Well he’s talking about himself, his own generation, William Carlos Williams . . .

DW: But what did he say? Why was that heave? Where does it come from?

MS: It comes from the natural rhythm of the English language. People say that we naturally talk in iambic pentameter.

DW: Right. You just did one. “We naturally talk in iambic pentameter.” We do.

MS: The only way I was able to begin hearing inflections and patterns in English was by learning French. And hearing my English speech patterns fucking up my French. That’s the only way I figured out how to hear it.

DW: Well, all of Victorian verse is pentameter.

MS: And that’s what Pound hated. He thought that it was “rotten.”

DW: Certainly in their time, the popular meter was Elizabethan. So it was something to be warned against. Right?

MS: Yeah. So what you’re saying is that Crane, he didn’t follow the rules. Cause he continued in that tradition.

DW: He absolutely ignored the rules. So what did he replace it with?

MS: Replace it with?

DW: You know what, more pentameter.

MS: He turned it up a notch.

DW: Yeah, he went up. “That’s bullshit, listen to this.” He would then do the equivalent of quotations from Marlowe and the Elizabethans.

MS: It’s like your poem “Ruins of a Great House.” That poem is all built on quotations and allusions.

DW: But you have to get this very right. The people who are writing very well . . . Thomas Hardy, right? Hardy was pentametrical, too. And certainly Browning. Isn’t Hart Crane from the fucking Midwest?

MS: Ohio.

DW: Who cares about a kid from the Midwest writing pentameter? It’s stupid. Isn’t it stupid?

MS: It’s bizarre.

DW: Exactly. That’s the same thing as stupid, you’re just using a fancy word. But all that proves is that you can’t fuck around with genius. That’s what he is. And a phenomenal genius because he was gifted.

MS: A prodigy.

DW: Yeah, in a way he was a prodigy, too. And he’s really stubborn, because he writes a whole book, The Bridge, in that meter. The Bridge and The Wasteland and Pound—same period.

MS: Why do you think so many people thought The Bridge was a failure?

DW: A failure? No, no.

MS: No, I don’t think so, but that was the initial response.

DW: Well, what you had was William Carlos Williams saying free verse is “American” verse. Everybody else said that this is “American” verse too. And Crane said . . . he was a drunk, eh?

MS: Yeah, you can’t do that anymore.

DW: Huh?

MS: You can’t be a rockstar like that anymore.

DW: [Laughs] Right. But I think a part of the persistence and the stubbornness had to do with being a drunk, too.

MS: Yeah. Cause he wrote drunk, too.

DW: But it’s bullshit. You can’t write drunk. I once tried it. You ever tried it?

MS: No.

DW: Forget it.

MS: Who wants to write drunk? You want to go out and party.

DW: It was an experiment. I said I’m gonna have six beers and write this masterpiece.

MS: [Laughs]

DW: Total shit. But you would think the impulse for great creativity would come from either alcohol or drugs.

MS: That pitch Crane lived on was always at the highest pitch of ecstasy. He was a poet of ecstasy and excess. So he needed the libations, the music.

DW: But the truth is that the poems are ecstatic.

MS: I totally agree.

DW: And when they’re no good they don’t make any sense. There are reams of Crane that don’t make any sense at all because he’s writing drunk.

MS: There’s some people who say that Crane only wrote good lines, because when you look at a poem as a whole there are passages that . . .

DW: You can’t read The Bridge and say he didn’t write good poems. There are parts of Crane that are as good as American prose, you know, the railroad squatters talking in “The River.” That is great prose stuff.

MS: Yeah, the hobos and stuff . . . there’s this line about them, “Holding to childhood like some termless play,” as if childhood could go on forever.

DW: I think he has to be seen as individualistic.

MS: I agree. He doesn’t fit into the canon very well.

DW: Also, you ever learn pentameter by heart?

MS: Like lines of pentameter? No.

DW: It’s a great kick. Because the meter, like from Marlowe, “Those walled garrisons will I subdue, / And write myself great lord of Africa . . .”

MS: Mhm, right. [Laughs]

DW: Fuck me . . . imagine an actor saying that. And even . . . [says something in Latin]—“O, run slowly, slowly, horses of the night!” Crane loved that sound! But that’s because he was from the Midwest, the middle of nowhere [laughs].

MS: He was from the middle of nowhere, so he could do whatever he wanted!

DW: No, I think it’s a tremendous love that he had for the Elizabethans.

MS: He loved the language that was just . . . “over the top” isn’t the right phrase, but exuberant . . .

DW: What I want you to do for your homework: Reread “The River” tonight. Really read it. You’ll see how it does these great things.

MS: It’s funny how you talk about “The River” because to be honest it was never my favorite passage.

DW: Really?

MS: “The Dance” with Pocahontas, and then “To Brooklyn Bridge,” but I’ll reread “The River,” yes. Has this line ever meant anything to you? “Imponderable the dinosaur sinks slow . . .” that’s one of the weirdest things in Crane’s poetry.

DW: What do you find weird about it?

MS: I don’t understand any of it.

DW: It’s an image of the thing coming out of the mud. You know it.

MS: Oh, as if he’s comparing Cape Hatteras to a dinosaur.

DW: It seems straight to me. “Imponderable the dinosaur,” that’s okay.

MS: Yeah, okay, okay.

DW: Can’t believe it . . .!

MS: And then it’s sinking into the sand . . . okay.

DW: Yeah . . . See, this can be bad Crane, you know? There’s a lot of [makes yucky sound], right? But the contrast is, when it hits . . .

MS: Because, he’s always swinging for the fences, and sometimes you strike out . . .

DW: Almost too often.

MS: [Laughs]

DW: No, really. Making a big hit of the line. He had examples . . . I was teaching it the other day, not Crane, Elizabethan poetry, Doctor Faustus, “See, see where Christ’s blood streams in the firmament!” And then Helen appears to Faust . . . I’m doing Marlowe now, not Crane. But what you’ll see is when the line comes out as Marlowe, it’s also like Crane, and he tried for that because he was capable of doing it as if he were Marlowe . . . when Faust sees Helen, what does he say?

MS: I don’t know.

DW: Everybody knows it: In astonishment at her beauty, he says what? He says, “Was this the face that launched a thousand ships?”

MS: Of course, yeah, yeah . . . Kind of like St. Lucia, fought over twelve times between the French and the English, the “Helen of the West Indies . . .”

DW: [Laughs] The next line is: “And burnt the topless towers of Illium?” but do you hear that echoing in Crane? That’s what Crane is going for . . .

MS: You can hear the pentameter very easily there.

DW: And of course, famous lines are like, “See, see where Christ’s blood streams in the firmament!” Faustus says that. Like at a sunset . . . Well, I’m extremely pleased that you know your Crane so well.

MS: Thank you.

DW: You teach him?

MS: No. I mean, I’m 26 years old, I just finished my degree.

DW: You know what I do in class? Joseph Brodsky used to do it, too.

MS: What?

DW: Get the class to recite. You ever do that?

MS: No. That’s so important though. It’s like you’re talking about with Shakespeare, to hear the meter. But what I’m trying to do right now is, you know, I’m teaching in Martinique, but then I also write book reviews for this literary magazine back in the states called Rain Taxi. But then I’m just trying to write poems while I’m over here.

DW: Tell me this:

“Elle est retrouveé.

Quoi?—L’Éternité.

C’est la mer alleé

Avec le soleil.”

MS: Rimbaud.

DW: Isn’t that something? Jesus. Oh, oh, oh!

MS: Exactly. Oh my god. Le Bateau Ivre, it gives me shivers just thinking about it. I found the best translation of Le Bateau Ivre a couple months ago.

DW: By whom?

MS: I don’t even know, I should probably know, but it translates Rimbaud into a contemporary vernacular idioms:

“I followed deadpan Rivers down and down,

And knew my haulers had let go the ropes.

Whooping redskins took my men as targets

And nailed them nude to technicolor posts.”

DW: But what is the French?

MS: I don’t remember it. Uh, I have no idea. That’d be a lot to memorize: The Drunken Boat in French. That’d be a task.

DW: Has there been a reassessment of Hart Crane in American literature? Or people don’t read him?

MS: No, people . . . when he killed himself, that was when his reputation was probably at its lowest. It has definitely been rising. I’ve heard one critic say that Crane constantly needs to be reintroduced, he constantly needs to be defended, it’s just like this perpetual thing, like the myth of Sisyphus . . . but yes, he’s in the syllabi, he’s being taught.

DW: Americans are not brought up with meter. They’re not brought up with poetry. If you try to get them to recite, they’re too embarrassed.

MS: It’s true, I remember.

DW: On the other hand, when you get a class reciting some great poems, it’ll tear your heart out.

MS: Did you have moments like that in Boston?

DW: Oh yeah, all the time. That’s why I’d do it. One I do all the time is Hardy or good Auden. You read Auden?

MS: Yeah, yeah.

DW: So who do you read today?

DW: Well, when I realized I was going off to Martinique, I thought, okay, what books am I bringing? How can I figure out the Caribbean? So I brought your Selected Poems, and I brought Robert Pinsky, and oh, Theodore Roethke, did you ever read Roethke?

DW: Well, when I realized I was going off to Martinique, I thought, okay, what books am I bringing? How can I figure out the Caribbean? So I brought your Selected Poems, and I brought Robert Pinsky, and oh, Theodore Roethke, did you ever read Roethke?

DW: Yeah.

SN: Roethke, r-o-e-t-h-k-e?

MS: Yeah, strange last name, very Polish, very German.

SN: Any more wine? What are we doing now?

DW: Let’s talk.

SN: I didn’t go swimming. I didn’t do my exercises.

MS: No? I’ve skipped the past two weeks, too. It’s the holidays.

SN: I know. My excuse, too.

DW: How would you like to go and eat? All of us.

SN: At the marina? We can go to the marina.

DW: It’s open?

SN: Yeah. It’s open at 6 o’clock. You know the marina?

MS: No, no.

SN: That’s our hangout, down the road.

DW: I wanna go like this then.

SN: You’re going like that, yeah.

DW: Should we call Peter?

SN: Uh, I can call him.

DW: Should we invite him?

SN: If he wants to. But he probably won’t want to. It’s a little late.

DW: What time is it right now?

SN: It’s almost 6:30.

DW: This guy is very bright [pointing to me].

SN: Is he bright?

DW: Very bright.

SN: Not only good looking, he’s bright, too? He’s blushing, that’s cute.

DW: Otherwise he’s the usual North Dakotan idiot.

SN: North Dakota? Or North Carolina?

MS: North Dakota, yeah.

SN: You’re from North Dakota?? Where, Fargo?

MS: Close, Grand Forks.

DW: Fargo?

MS: No, not Fargo.

SN: You know that movie? You know Frances McDormand? She was a student of Derek’s.

MS: Wait, what?

SN: Yeah, she’s great. She’s married to a Cohen.

MS: She’s in a lot of their movies.

SN: She was a student of his in a play at Yale.

MS: Wow.

DW: Sweetheart, I’m getting hungry. Let’s call Peter and come back.

APPENDIX: THE ORIGINAL INTERVIEW QUESTIONS

- Do you remember when you first discovered Hart Crane? There is a magnificent series of video-documentaries called Voices and Visions, where you speak in Hart Crane’s documentary. What has Hart Crane meant to your writing and your reading life? Did his Key West: An Island Sheaf mean anything to you in particular?

- You wrote an epic poem, or a long poem, and so did Crane. What do you think of The Bridge? In an interview elsewhere you write that Crane “didn’t have a hero in his Bridge. And—I think—that’s why it collapsed. It didn’t’ have a central figure.” Was the poem a failure, as so many critics contend?

- A wonderful tension I feel in your work has been a need for lyrical intensity coupled with narrative drive. One can think of The Schooner Flight, for example. How do you view these two different aspects in your poetry—are they complimentary or antagonistic forces? Did you ever feel a conscious necessity to reconcile them in any way for your art? I also know this was one problem people saw in The Bridge: how Crane tried to fashion an epic out of lyrical sequences, that there was some kind of fundamental problem of genre in his poem. Do you think narrative poems have a place in the 21st century, or should narrative remain wholly the work of novelists, for example?

- There is a well-known passage in Hemingway’s A Moveable Feast where he describes how he learned to depict landscape in his writing by studying the paintings of Cézanne. Can you explain how your painting has influenced your poetry, and vice versa? Has your writing been likewise influenced by specific painters or painting styles?

- There’s a remarkable passage in a letter by Keats that I would like to discuss with you. In the letter Keats is describing how he is giving up ‘Hyperion’ because it is too ‘Miltonic’ and ‘artful.’ Later on in the letter he suggests an experiment—that his reader pick out some lines from the poem and put an ‘x’ next to the ‘false beauty proceeding from art’ and a double line next to ‘the true voice of feeling.’ There’s something incredibly fascinating about Keats’ desire to separate mere ‘art’ (which led to falseness) from what he calls ‘the true voice of feeling.’ Mr. Walcott, how do you know when you’ve written a poem that comes from ‘the true voice of feeling’ rather than the ‘false beauty proceeding from art’? Where does a poem start for you? In a line, in prosody, meter, image, rhyme?

- When you look at the careers of a lot of poets, it takes them a long time to produce their first book. I think Robert Frost was 36 or 37 years old when he published his first book of poems. But you showed remarkable confidence early on in your career. You self-published when you were 19 years old, for example. Where did that confidence come from? I know you knew early on you wanted to be a poet, but a sense of vocation doesn’t automatically come with the necessary confidence. Also, you did the other thing, you continued to last and never were a one-hit wonder. Where did your endurance come from?

- I’d like to begin this question by quoting you from another interview. “I come from a place that likes grandeur,” you write. “It likes large gestures; it is not inhibited by flourish; it is a rhetorical society; it is a society of physical performance; it is a society of style. The highest achievement of style is rhetoric, as it is in speech and performance. It’s better to be large and to make huge gestures than to be modest and do tiptoeing types of presentations of oneself” (Paris Review). I feel, in American poetry at least, that a lot of it is smugly ironic, or understated, or overly intellectual, or that it is afraid of the grand gesture, it is afraid to approach the grand subjects—death, god, love, whatever—for fear of getting them wrong or of simply being cliché. It is almost as if the great subjects were no longer the business of poetry. What do you make of this? Can poetry in the 21st century still approach the grand subjects with vigor or have they been permanently coopted by other more contemporary artistic mediums?

- At base, what is the impulse to write poetry? An act of naming, an act of benediction, or . . .?

- It has been six years since you’ve published White Egrets. What does that book mean to you now? How did it mark a turn in your writing style? I feel like the trajectory of your aesthetic marks an opening, your lines have become much plainer than they were in In a Green Night, for example. Do you agree with that sentiment?

- You’re an amazing travel writer. How do you write when you travel? Do you take time out of the actual travel time to write, or do you write after all the traveling is done, or both?

- To begin this question, I’m wondering if I could recite a passage to you from your essay What The Twilight Says: “After one had survived the adolescence of prejudice there was nothing to justify. Once the New World black had tried to prove that he was as good as his master, when he should have proven not his equality but his difference. It was this distance that could command attention without pleading for respect . . . Yet most of our literature loitered in the pathos of sociology, self-pitying and patronized . . . And their poems remained laments, their novels propaganda tracts, as if one general apology on behalf of the past would supplant imagination, would spare them the necessity of great art. Pastoralists of the African revival should know that what is needed is not new names for old things, or old names for old things, but the faith of using the old names anew.” Do you think the young Caribbean writer has made progress toward renaming its world, that the Caribbean writer has made progress toward great art that is beyond the foibles of the past?

- American universities were once a safe place for a certain regressive, or even transgressive, experience; increasingly, however, they have become places of censure and prohibition. In the name of emotional well-being, college students are increasingly demanding protection from words and ideas they don’t like or find harmful. I’m thinking in particular of concepts like trigger warnings, macroaggressions, safe spaces, basically what has been articulated as the coddling of the American mind. What is your opinion of the extraordinary fragility that most American students and young people now demonstrate? Is this helpful for the study of literature in particular? Is this how we should be experiencing literature?

- “How do you balance the need to become a great poet with the need to become a great man? Is there a point, at which the effort of writing and putting one’s life and one’s thoughts into words comes at a cost to what one could contribute to a community, to a neighborhood, to a family, to relationships?”

- Do you have any advice to young writers embarking out on a career in poetry? I know when the same question was asked of T.S. Eliot, he said to find something else to do. What does it take to be a poet?

Click here to purchase Selected Poems of Derek Walcott at your local independent bookstore

Click here to purchase White Egrets at your local independent bookstore

Click here to purchase Hart Crane: Complete Poems and Selected Letters at your local independent bookstore

Rain Taxi Online Edition Fall 2016 | © Rain Taxi, Inc. 2016

The Defender

How the Legendary Black Newspaper Changed America

How the Legendary Black Newspaper Changed America

From the Age of the Pullman Porters to the Age of Obama

Ethan Michaeli

Houghton Mifflin Harcourt ($32)

by Spencer Dew

Journalistic style exists along a spectrum, from the terse, skim-conducive relay of stats and facts to the immersive long-form, unraveling complexities. Ethan Michaeli’s book The Defender is an example of the first, which is a profound disappointment considering the richness of his subject matter and the relevancy critical analysis of it would hold for our country’s current racial crises.

The first problem here is one of chronological scale. To offer a survey of the history of this storied newspaper, one simply needs more space (and this is already a very long book). A seeming lack of journalistic discipline comes into play here, too; Michaeli’s narrative lacks focus, gives too much time to tangents. We learn a great deal about the adventures of aviatrix Bessie Coleman, but this feels like a side project. The final two chapters offer an autobiographical coda, likewise misplaced.

The subtitle, as thesis, points to a second stumbling block. Michaeli wants to convince his readers of the Defender’s ongoing relevance. This may not be a winnable fight, but the strategy employed here, which hinges on the fact that the Defender played a role in Obama’s rise to prominence, is not merely thin as an argument but reduces “relevance” to mere electoral impact while simultaneously presenting The Defender as anachronistically monolithic. The paper’s role in the age of the Pullman Porters was not its role in 2008. The newspaper that brought about the Great Migration, pushed for anti-lynching legislation, and called attention to the hypocrisy of black soldiers dying for democracy overseas while unable to experience it at home is, indeed, the same newspaper that sponsors the yearly Bud Billiken parade, an event that is at once family-friendly entertainment and an old-school Chicago style king-making event. But The Defender is not today what it once was; to pretend otherwise does a disservice to the past as well as to the multivalent media present, misrepresenting the newspaper’s uniqueness and ignoring context.

On the early years, under founding editor Robert Abbott, Michaeli heats up content covered with more spice in Roi Ottley’s classic The Lonely Warrior. Oddly, he opts to clean up some parts, playing down the emphasis on shock and titillation and absolving The Defender of any role in inciting retaliatory violence during the 1919 Chicago Race Riot. Michaeli seems to regret the presence of “salacious details” in the newspaper, and does not address the claim, advanced by Ottley, that Abbott knew some of the lynching stories he published to be fictional, justifying their publication with the fact that much racist violence went unknown. On the Race Riot, Michaeli’s Abbott remains cool and high-minded, pleading to his readers that “this is not time to solve the race question”; no mention is made of salaciousness in coverage here, nor of “box scores” of the dead and wounded run as a daily tally. Michaeli’s Abbott, ultimately, is a cardboard, one-note guy; he is motivated merely by the “belief that what African American people needed was a newspaper that would ‘wake them up,’ expose the atrocities of the southern system, and make demands for justice.” This ignores at least two fascinating and interwoven factors in the newspaper’s development: the media milieu in which it was competing for a name and the elaborate system of class and status in the Black Metropolis of Chicago’s South Side. Of its rival papers, The Chicago Bee gets only one notice in the whole book, but competition between The Defender and it and The Whip helped shape not only the distinctive voice and focus of The Defender but also its high society niche.

Michaeli offers some nice details on Big Bill Thompson’s important 1927 mayoral reelection campaign. As a corrective to the more widely known narrative of Mayor Anton Cermak as the coalition builder who united the mosaic of ethnic Chicago, Thompson’s outreach to (and dependence on) voters in the African American wards needs to be known. Michaeli’s attention to the racist propaganda his Democratic opponents used against him remains timely in this election season.

Michaeli also locates Abbott as following in the footsteps of Ida B. Wells, but with the editor’s famous feud with Marcus Garvey he is particularly negligent, rehashing clichés while not only once again removing some of the vinegar from the story but also refusing to reconsider the actions and players involved. Garvey especially is past due for reconsideration (Sylvester Johnson, now at Northwestern University, recently reframed Garvey in response to colonialism, which will shape how people think about Garvey’s career for some time) but Michaeli does not bother. Abbott’s beef with the Jamaican is likewise, surely, about far more than differing thoughts on race. That the men were competing in the newspaper business might be worthy of consideration. Abbott goes to J. Edgar Hoover’s FBI to help bring down Garvey, which is a stunning move, in retrospect. This is precisely what I mean when I say that the subject matter here is rich. Michaeli, however, gives us a treatment that is not just tepid, but reads as troublingly dismissive, as when he states that Garvey

appointed his own ambassadors, generals, and cabinet members, bestowing titles on his followers such as ‘Supreme Potentate’ or ‘Lady Commander of the Order of the Nile.’ Many of his American followers, though they had no intention of ever leaving the country, seized on the chance to transform themselves, even for just one day, by exchanging their workaday clothes for uniforms and marching proudly through the heart of their city.

Not only did Garvey, with such uniforms, change America (consider the Nation of Islam and the Black Panthers, to name two post-Garveyite movements), he was also tweaking an established fraternal society form (which dominates the pages, in words and photographs, of the Chicago Defender in the early twentieth century). Again, context is strikingly absent in Michaeli’s coverage. We hear, in these pages, that Abbott becomes a Baha’i, but we learn nothing about that religion’s relation to Chicago, nor do we hear how scathing (and often hilariously so) Abbott’s Defender was on religion. Michaeli presents the conversion as mere rejection of Christianity’s connection to racism; this oversimplifies Abbott’s interest in—and, really, proselytization for, in the pages of his newspaper—Baha’i, and it overlooks his equally passionate distaste for what he took to be metaphysical hokum or the hypocrisy of faith-for-sale. On the Great Migration, Michaeli tells us about a Tribune editorial entitled “Black Man, Stay South!” but we never hear about The Defender’s own warnings to new migrants about propriety (including similar sentiments urging those Southerners who don’t learn to behave—in the case of one cartoon, this involves fishing, shoeless, from city bridges—to head back to the South.) Abbott and his newspaper deserve a reading with more analysis.

After Abbott’s tenure, Michaeli chugs along, hitting major moments in history until, without explanation, he more or less skips the 1970s and 1980s. Again, odd editorial choices reign: the Jackson Five are mentioned, but there’s no coverage of either of Jesse Jackson’s presidential bids. Then we get to those final chapters, and history gives way to memoir. “Working at The Defender allowed me to see the truth about America,” Michaeli writes, “that ‘race’ is a pernicious lie that permeates our laws and customs, revived in each generation by entrenched interests that threaten to undermine the entire national enterprise, just as it is challenged in each generation by a courageous few who believe that this nation can truly become a bastion of justice and equality.” This, if you’ll pardon the pun, offers a black-and-white reading of a dynamic that any issue of The Defender shows to be complex. As the problem of race in America has increasing, unbearable urgency, we could all use some clear and critical analysis of The Defender’s robust and multivalent role throughout history. This, unfortunately, is not that book.

Click here to purchase this book at your local independent bookstore

Rain Taxi Online Edition Fall 2016 | © Rain Taxi, Inc. 2016

Disorder 299.00

Aby Kaupang and Matthew Cooperman

Aby Kaupang and Matthew Cooperman

Essay Press

by Carol Ciavonne

On the way to the psych ward there are elevators that are glass and elevators that are steel this is clear most designers and children who do not die in helicopters prefer glass elevators

If Disorder 299.00 were not a digital chapbook, it would have to be bound in steel and glass. The photocopied cover, in fact, appears to be steel, printed with an image of faceless (removed ovals of steel) mother and father, and their lovely (intact) baby. Mother and father are dressed in conventionally gendered attire, as if to show the traditional expectations of parenthood. But this will not be a traditional experience for poets Aby Kaupang and Matthew Cooperman, or for the reader, and the title of the book is the first indication.

The girl began, and then so did the book, a mirror for sorrow

or anger or fear.

For Kaupang and Cooperman, this is family life; uncountable trips to medical entities to try to find help for Maya, who is autistic and also has life-endangering physical problems.

Again and again at the ER

soothing her body. The daughter didn’t eat, didn’t

sleep, didn’t laugh, didn’t shit, didn’t walk anymore. We

went for a long visit. Doctors said erythromycin, they said

tape a bag to her shoulder. We went again when they said

she was crazy, a crazy summer when our little girl lived with

other un-specifiable children.

Maya is labeled in the hospital system as 299.00 “unspecified diagnosis.” Although this label is troublingly nonsensical, labels are a literal fact of life for the family. Aby is MOC (Mother of Child) in the endless documents of hospital visits, Matthew is FOC.

I went to the pharmacy she was not there

I went to the surgeon she was not

there

I went to the TV the nurses’ station the family respite station

she was not there I was not therea we everywhere

MOCs and FOCs as assemblies

of pills

The authors have so much of labeling that they invent a word for themselves, the other MOCs and FOCs, and the children being cared for.

cardiums: heart bouquets, whack jobs

staring

they that were the cardiums wore it on their sleeves their crimson gowns

forehead temples and they wagoned there were they that were in the wagons

and those that carted others in wagons it was numerous who or who all were cardi-

umsthey passed through the foyer we drank coffee averting our eyes from sadness to

sea tanks we admired the sea tanks we too being cardiums

Kaupang and Cooperman write in a variety of syntax, in the distancing acronyms as well as the personal I or we, their experience as helpless, sometimes desperate parents, and as individuals who do sometimes vehemently desire their “normal” lives back.

The difficulties of caring for Maya physically, and the emotional roil of her health and behavior are laid out with no punches pulled. In this work, it’s clear that Maya’s condition compels the poets to constantly question themselves, as parents, as a couple, and as individuals. Their lives are often tuned simply to survival mode—Maya’s actual survival, and their own emotional survival. It’s a topic requiring deeply personal exposure of pain, anger, guilt, fear, and love.

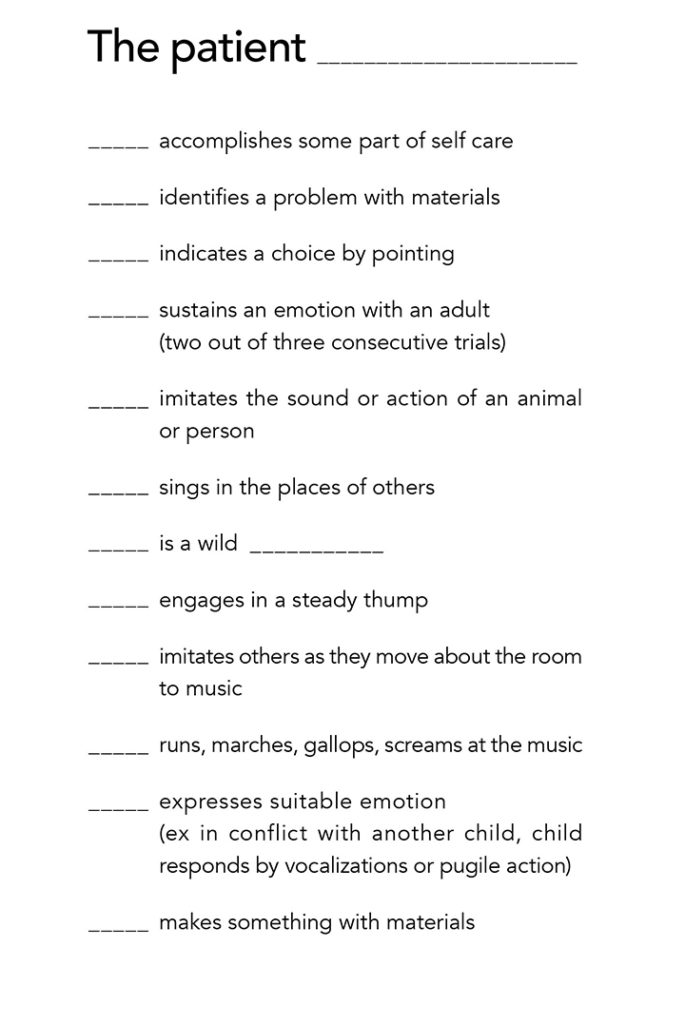

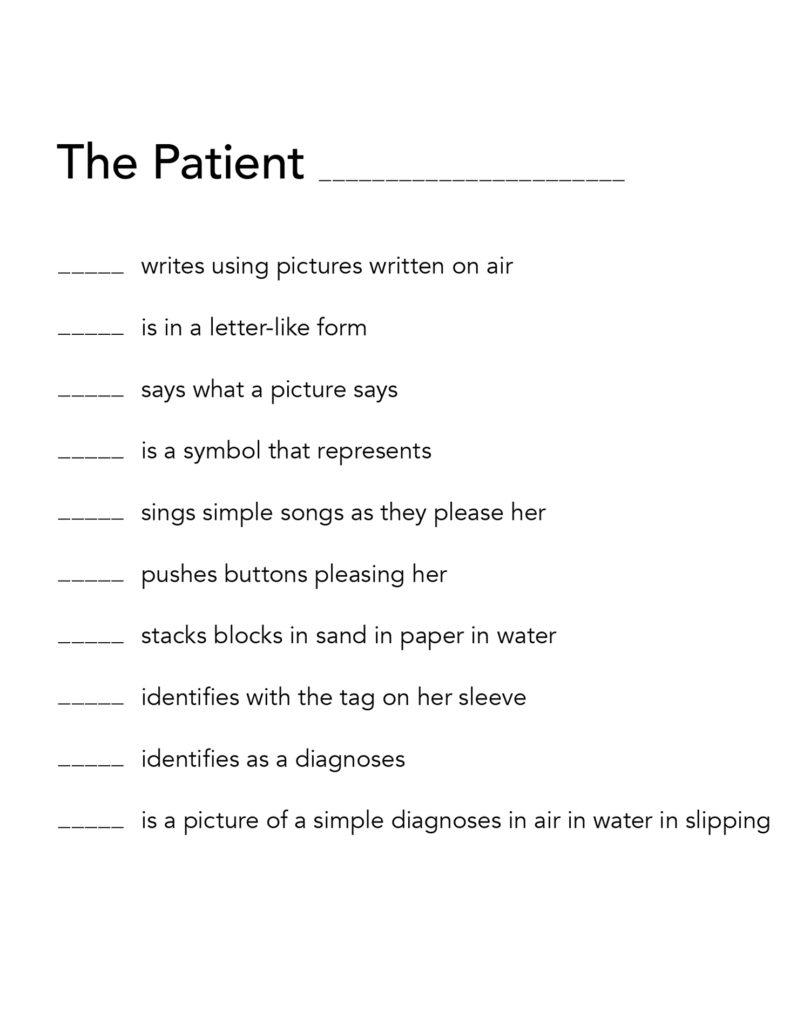

The structure of the book, using actual documents and forms, personal statements, statistics and fragments of description, is a near perfect dovetailing of content to form. The documents are visual evidence of the mind-numbing and heart-breaking forms that the authors must use to describe/report their lives and Maya’s within the hospital system. In some, both the child and the parents are described in the dry clinical style that seems to question the actions and observations of the parents. “The cause is unknown and that is vexing to the mother.” The forms, too, do not fit the patient, and the listed behaviors are impossible to check off. The patient is a form from the hospital; The Patient is a form created by the authors that demonstrates how elusive any description of behavior can be, and is especially so in Maya’s case.

As with the re-labeling, in redefining the limiting clinical language, the authors rewrite the hospital experience into one more human, less rigid, and somehow hopeful—more Maya, her actuality and possibility. Some of the textual pieces are clearly written by one poet or the other, illustrating how each individual parent sees and reacts to events, and yet the reproduced documents and the use of “we” also make it clear that this is shared experience. The fragmented syntax, a staple in post-modern work, makes particular sense in interpreting and reading the lives of Maya and her parents, with all the jolts, reverses, and accelerations of living with autism. This is a book that could be given to other parents of children in Maya’s situation, since one of poetry’s great virtues is to help us know that we aren’t alone. Even the incidents in the book that are particular to Cooperman’s and Kaupang’s experience resonate; the particular in poetry so often pierces a quite different heart. Some of the lines will be familiar to anyone who has had to be in a hospital with a loved one, and the lines are stark:

the truth of the hospital system is

death prevention and sometimes

death theft and the truth of the

ER more so . . .

Some of the lines are a personal revelation of love and the sadness of knowing that Maya’s life will not be as they had imagined it:

Present is

this gift of the daughter’s enormous need

and absent is the dream of her own dream

a blue house and yellow car, two Chinese dogs

and a child of her own.

Some are the experience every parent knows of that edge of love and fear:

I staunch the fear of my own death and her

perpetual childhood. Today was a good day.

The open and sometimes head-on approach in Disorder 299.00 includes the poets’ relating that some readers of the manuscript have questioned whether they love their daughter. No one who has not lived with the extreme rigors of caring for an autistic (and in these years, very ill) child, with the ever present fear of calamity, can completely understand the impact of a shared life that can lurch from control to chaos on an hourly basis, but Cooperman and Kaupang have made beautiful, blended, astonishingly honest and profoundly moving poetry of their experience. Although Disorder 299.00 makes a fine digital chapbook, I would love to see it in print also; it’s a book that needs to be on the small table in the hospital waiting room, where words of steel for strength, glass for looking through and into, are always needed.

Early in the book, the authors ask, by way of quieting the reader’s apprehensions of the future,

What is there to say of this child? She lived, lives through

this. So did we. You want to know more about her. So did

and do we.

The final poem is a portrait of Maya today.

WORDS FOR THOSE WHO DON’T SPEAK THEM

when our daughter rises it is with and without her mouth

she sings in phones of plosive thirds that do not complete

the scheme and yet they are awake they are very awake

third third third

she sings with her body and to her body a plateau of sinew

to hold a twitch of song