Interviewed by Rob Couteau

Interviewed by Rob Couteau

Danny Goldberg has been passionately involved in the music business ever since the late 1960s. At the age of nineteen, he reviewed the Woodstock Festival for Billboard and later wrote for publications such as Rolling Stone and the Village Voice. In 1980 he co-produced and co-directed No Nukes, a film documenting the 1979 “No Nukes” concert at Madison Square Garden. He has since held many posts in the music and entertainment fields: president of Atlantic Records, Chairman of Warner Bros. Records, and CEO of Air America Radio among them. In 1999 he created his own independent label, Artemis Records, and in 2007 he formed Gold Village Entertainment, an artist management company that he still presides over in New York. A devoted political advocate, he serves on the Board of Directors of The Nation Institute, The ACLU Foundation of Southern California, Americans for Peace Now, Brave New Films, and Public Citizen.

Goldberg is currently working on a memoir about his friendship with Kurt Cobain, the former lead singer of the band Nirvana, which he managed in the 1990s. In addition to his latest book In Search of the Lost Chord: 1967 and the Hippie Idea (Akashic Books, $25.95), he is also the author of Dispatches from the Culture Wars: How The Left Lost Teen Spirit (Miramax Books, 2003) and Bumping Into Geniuses: My Life Inside The Rock and Roll Business (Gotham Books, 2008). This interview was conducted in February of 2018.

Rob Couteau: While reading In Search of the Lost Chord, I began to wonder if the principle thread running through the counterculture movement is the theme of agape, or universal love: a term you use at various times.

Rob Couteau: While reading In Search of the Lost Chord, I began to wonder if the principle thread running through the counterculture movement is the theme of agape, or universal love: a term you use at various times.

Danny Goldberg: I don’t think there was just one counterculture going on. So, I’m not sure that all the members of the SDS, who were an important part of the fabric of the ’60s, would agree. It depends on how you define counterculture. Tom Hayden used the word “counterculture” to distinguish it from political radicalism. Others use it in a way that includes, in its purest sense, the “hippie idea,” and what Allen Ginsberg was talking about a lot of the time, and the Beatles with “All You Need is Love.” To me, agape was certainly the aspiration.

RC: If one broadens the definition of agape, one could say that the long-term goal, even for the SDS, was a concern beyond the personal self, yes?

DG: Yes, it was. That’s where there was commonality. The policy goals—to end the war, to have more economic egalitarianism, to end racism and sexism—were consistent with the spiritual values. But there were certain people who were rationalists, who were informed by Marx, and who didn’t believe in mysticism, but who had an ethical construct that was their guiding light. Again, the goals and issues that were prevalent in ’67—antiracism, antiwar—were consistent with that. Not everyone who was a radical liked mysticism, Allen Ginsberg, the Maharishi, or Donovan’s records, but everyone who was a hippie was against the war.

RC: You begin with a wonderfully nuanced account of the January ’67 Be-In. Was this the first collective expression of agape at that time?

DG: It was the biggest one until that time. There were smaller things happening all during ’66. In Haight-Ashbury there were concerts, and things in the park that were organized. But the Be-In increased the scale of that experience by a significant factor.

RC: Did it serve as an ideal template for what the counterculture represented and for what might be possible on a broader scale in the future?

DG: That was the hope. It was a moment in time. And then, dealing with the reality of the day after, or the week or month after, was a different set of conversations. There were also Be-Ins in New York and Los Angeles on Easter Sunday. And in between, I’m sure there were plenty of others in different parts of the country. I think that was the idea, that it could provide an example and prove the concept, at least for an afternoon.

RC: What you just said about the aftermath reminds me of what Joseph Campbell says in his Power of Myth series. Everyone remembers that he said “Follow your bliss,” but he also said we must follow our “blisters.”

DG: I didn’t remember that, but I’m definitely going to use it going forward. It’s a terrific modification.

RC: I thought of this when you wrote about the Be-In, or perhaps it was one of those other events, when Allen Ginsberg went on stage and said: Now we have to focus on our “litter karma.”

DG: Yes! That was the end of the Be-In, when he told everyone to clean up. To the extent that there was one person who was the closest thing to embodying a lot of what was best in that incoming culture, it was him. For me, the political hero was Dr. King, and the cultural hero was Allen Ginsberg. They’re human beings, they had imperfections, but they came the closest to being role models that I would retrospectively want to look up to.

RC: They were so different in terms of personal style, yet their hearts were focused upon the same thing. What did they represent for you?

DG: To me, King is on a pedestal of his own, a kind of American saint. I often listen to his speeches and sermons. The more time that goes by, the more I’m impressed by how extraordinary he was as a being. Not just his political effects, but also as a spiritual prophet. He talked so much about the soul and the inner world, and he made it come alive. He’s one of the great figures in Western history, and he happened to live at that time, and was part of the mix. In addition to how extraordinarily brilliant and morally grounded he was—and effective and tactically brilliant—he had such a difficult time with the people around him. It was not as if he got a lot of support. To go back, and to realize how many opponents he had in both the black and white community, makes his steadfastness even more remarkable. As far as we know, he never took psychedelics, but he didn’t have to. He was there. He talked about agape all the time. He would conduct sermons where he would say: The Greeks talked about three different kinds of love. This was part of his regular language. It’s just incredible that he lived; he’s one of the greatest Americans, right in the top five all-time greatest. But in the context of that period, a lot of people that I admired—the black power movement and the hippies—didn’t necessarily realize that. I, myself, as a kid, didn’t appreciate him as much as I do now. And he knew who his enemies were: J. Edgar Hoover, and all the mainstream civil rights groups, and the young radicals! And then, within the SCLC, there was complete infighting and chaos—all the time. It’s unbelievable that he stayed centered through all that; it’s saintly. There’s no other word for it.

In terms of Allen Ginsberg, he had just an unbelievable life. Certainly, along with On the Road, “Howl” is one of the two most important works of the Beatnik culture. And unlike Kerouac, Ginsberg continued to be relevant in every subsequent decade of his life. In the period of time that I write about he was particularly powerful culturally, because he was almost unique in his ability to be accepted and respected in all these different subcultures, which otherwise detested one another. The fact that everyone from Emmett Grogan to William F. Buckley accepted Allen Ginsberg is mind-blowing. As Whitman writes, he “contained multitudes.” Over Allen’s bed, in the last place he lived, was a picture of Whitman. It was the only picture over his bed; it wasn’t as if he had a zillion pictures. So, that was certainly his north star.

My favorite poem by Allen is “Wichita Vortex Sutra.” That, to me, is his quintessential ’60s poem. It’s a fully mature commentary on what was happening in America at that time. I recently wrote a review of the Ken Burns documentary of the Vietnam War, and I said: “If you want to know what was actually happening, you’re better off reading ‘Wichita Vortex Sutra.’”

RC: Is the broadening awareness that we possess today about narcissism connected to the blossoming of agape in the ‘60s, especially since love and empathy are the antidotes of narcissism?

DG: The way that it’s often used, “The ’60s” is a kind of shorthand for the different countercultural rebellions, because obviously there were plenty of other things happening at that time, too. In some instances, the ’60s helped to be an antidote of narcissism, but in others it reinforced narcissism. That’s the whole thing even about psychedelic experience. Ram Dass says that if you think everyone is God, you’re a saint, but if you think only you’re God, they put you in a lunatic asylum. So, there’s this balance. There were people who became more narcissistic; for example, the cult leaders, the ultimate being Charles Manson. But he was by no means the only one who developed this kind of cult of personality by wrapping himself in the ’60s and the psychedelic world. There were others who saw it as an antidote, and it drew them closer to egalitarianism or agape.

RC: As you chronicle in your book, psychedelics played an enormous role during this period. What insights did you gain from dropping acid, and how were you able to integrate them into your life?

DG: It imbued me with a kind of optimism that I didn’t have before. It was like being given permission to be happy: that it doesn’t mean that you’re intellectually unserious to have joy or happiness. My notion of what it was to be a smart person was based on whatever the intellectual influences were that I grew up around. The canon in my home was T.S. Eliot, Eugene O’Neill, J.D. Salinger, Bernard Malamud. It was all: “To be smart you had to be depressed and cynical” and people who were too happy must be stupid or not have depth. It’s like that scene in Annie Hall when Woody Allen—who I doubt ever took LSD—says: “Obviously, people who are happy are just stupid.” You know, that kind of “modernism.” And it really allowed me to just experience the joy of looking at a strawberry, or to just feel the moment. That was a big deal to me, because it was the closest thing to a spiritual experience I had at that point. It also opened the door to the idea that, even if I wasn’t attracted to the limited religious options that were presented to me while I was growing up, there was something bigger than just the external reality of what your grades were, how much money you made, what your résumé said, and all that sort of thing. This paradigm shift was greatly liberating; it allowed me to have a little more confidence for the rest of my life.

For me, it was particularly helpful because I was not a good student. According to my parents, I had a so-called high IQ, and I did well on the SATs. But today I’d probably be considered ADD. I had a hard time at homework. I never found teachers that “got” me. I was just this huge failure in my mind, at fourteen or fifteen, because I wasn’t getting good grades. So my parents, who thought they had this smart kid, were disappointed. They were very lovely people; I miss my parents. But I was pretty unhappy with their disappointment in me at that time, particularly my mother’s. The psychedelic experience gave me this other way of defining myself. And then it turned out that there were all these other people that were going through the same thing. And so, it was like, overnight, I’m part of a community. I’d never been a part of a community; I’d been a loner. Maybe I had one friend every year, or two at the most, and we didn’t even like each other that much, but we were all that we had. But then, suddenly, I was part of this community, where you just look down the street and feel connected with somebody. Psychedelics were part of that; it wasn’t only politics or all the other things. So I’m very grateful for that. But ultimately, I felt it was no longer useful. I went completely antidrug, personally. I was arrested before my eighteenth birthday, and I was so freaked out that I’d put myself in that position that I just stopped. I’m not saying that I never did drugs again, but I didn’t do it for a long, long time. In terms of psychedelics, I haven’t felt the calling to revisit it since my early twenties. But I’m very grateful for the role it played. It opened me up to the idea of spirituality in a way that nothing else in my life had, until that point.

RC: What was the connection between agape and LSD?

DG: For me, and for many of those who took LSD—not everybody, but certainly in my experience with it and with that of many others such as Allen Ginsberg, Tim Leary, and Richard Alpert—it triggered a consciousness of love. People would look at a glass and say, “God is in the glass; the molecules are all from the same energy,” and see this commonality. It’s similar to what Aldous Huxley wrote about, a decade earlier, regarding his mescaline experiences. It gave us a temporary experience of universal love; it was not permanent. And how people reacted when they came down varied. Not everybody had that experience; there were those who had bad experiences. But what made it so popular for a lot of us was this feeling of enormous love that wasn’t just transactional or romantic love but was love of the universe: of whatever was in front of you. That was something that a lot of us experienced, and it was what we loved about it.

RC: One of the charming things about your book is the evocative title, which is borrowed from a Moody Blues song. What’s the metaphoric significance of the “Lost Chord” for you, and what are the notes it comprises?

DG: The metaphor alludes to what you said earlier, which was that there was this period that’s largely been forgotten. It was before the cartoon version of the ’60s became the established narrative of most of the media. Before the assassinations, and some of the darkest aspects of it, there was this genuinely idealistic feeling. It was what I felt as a teenager; it’s what inspired me. Why it’s “Lost” is that the media and the cartoon version, with the co-option of many of the external symbols, replaced this feeling with a sort of plastic version of the ’60s. And it’s a “Chord” because it was a product of a lot of different things that, together, if you were a teenager at that time, you were experiencing.

I very much wrote the book based on what I, as a kid, was influenced by—there were many things going on that were equally important to other people. Even though it’s a history and not a memoir, it’s a history of things told through my eyes: of things I was inspired by. This includes the antiwar movement, civil rights, psychedelics, and music. It includes a general curiosity about non-Western spiritual paths and an openness to it. And it includes an empowerment of young people that was also temporary but which, in the moment, felt very exciting. It really did feel as if everything was changing for the better and that one could be part of it—even if you were sixteen, seventeen, or eighteen. This combination of things didn’t last. I would argue that, certainly, by the end of ’68, the balance of those notes was different. Again, we lost two of our great political leaders, Robert Kennedy and Dr. King. And Nixon gets elected by the end. And in general, the drugs got darker. There was more speed and heroin, and there were drug dealers instead of psychedelic missionaries. It didn’t disappear, but it changed by then. You know, it’s arbitrary; it wasn’t exactly the calendar dates. But the collection of things that happened in ’67 was a good stand-in for a collection of feelings that I remembered as creating hopefulness, an optimism that society might get better.

RC: You also take 1967 and hold it up as a sort of prism through which many other events in the ’60s are seen. And I think that writing a subjective history of the ’60s is in keeping with the spirit of the time.

DG: By definition, any history is subjective; I’m just being open about it. CNN’s history of the ‘60s is also highly subjective. Part of it was this beginning of decentralization, of people in small communities thinking that their opinions mattered. Their ideas about God, sexuality, psychedelics, spirituality: all these things mattered, as opposed to just being told what to do by the authorities. The results weren’t all good, but that was the nature of the time. Initially, the phrase “a gathering of the tribes” just meant the radicals and hippies. But there were hundreds of tribes, because everybody in every living room was a tribe at that point. When I did the publicity stuff for the book, people would come up to me, and everyone would have their own story, and they weren’t exactly the same stories. For some, it was seeing Jimi Hendrix; for others, it was joining a sit-in at a college president’s office or studying TM. For some people, drugs were a big part of it; for others, drugs weren’t a part of it at all. So it’s inherently a subjective experience. But it’s my version of it, and I think many others saw the same picture that I saw.

RC: Your book certainly brought back many memories of things both big and small. For example, you talk about Jung’s Introduction to the I Ching: as you say, that became a huge best seller at the time.

DG: Oh, my God, the I Ching was such a big deal for me in high school! Even decades later, I’d meet people who would say: “You turned me on to the I Ching,” or that I’d remember had turned me on to the I Ching. It represented a way of thinking about cosmic issues in a different perspective, without having to join a church or sign onto any set of behavioral agreements. And it was a way of honoring the idea that there was another consciousness that’s smarter than the conversations that we have in day-to-day life.

In retrospect, the fact that Jung wrote the Introduction was such a big deal, because he was validating it from his perspective. I’ve reread his Intro; it’s fantastic. I don’t know as much about Jung as I’d like to, but what I know about him is just so cool; he’s such an interesting figure. And obviously, the I Ching long predated the ’60s. As I say, the ideas and values of the ’60s were not original to that time; they’d been around for centuries. What was unique was that they became part of mass culture.

RC: When things reach an extreme point, sometimes they can turn into their opposite, which is the fundamental principal behind the changing hexagram lines in the I Ching. How much of what occurred was due to a counterpoint reaction to the repressive atmosphere of the ’50s?

DG: Tim Leary said that you could not understand the ’60s without understanding the ’50s. Certainly, Leary was a guy who very much felt that it was connected. Although the Beats emerged in the ’50s, they were an influence on a lot of ’60s people. The Grateful Dead bonded over their shared enthusiasm for Jack Kerouac. Ken Kesey, an important ’60s figure, had Neal Cassady on the bus. The civil rights movement took a huge leap forward in the ’50s with the Montgomery Bus Boycott. The roots of the Vietnam War were in the ‘50s: the reaction to the Korean War, the Cold War, and the first military advisors in Vietnam. There was the general mass culture in the ’50s, which was, to a lot of people, pretty shallow. There were only three television channels, and there was a fake, plastic notion of what families were like. It seemed as if one day that was reality, and the next day it was a joke. Somewhere in between there was Mad magazine making fun of this, and that set the stage for the joke side. You know, it’s a continuum. There isn’t anything in the ’60s that you can’t connect to something in the ’50s. In that one chapter in the book, I tried to give some context to this, so it wasn’t coming out of nowhere.

RC: Besides Dr. King, probably nobody did more to advance the cause of civil rights in the ’60s than Robert Kennedy, although that’s often ignored by mass media. What isn’t widely known is that RFK was not necessarily opposed to the intelligent use of LSD. During a Congressional probe on LSD experimentation by federal agencies, Senator Kennedy was quoted as saying: “I think we have given too much emphasis and so much attention to the fact that [LSD] can be dangerous and that it can hurt an individual who uses it . . . that perhaps to some extent we have lost sight of the fact that it can be very, very helpful in our society if used properly.”

DG: I wasn’t aware of that, and if I had been I certainly would have included it in the book! But I’m not surprised. I very much view Robert Kennedy as a ’60s character. The Jefferson Airplane, who’d never supported any other candidate that I know of, publicly supported him. And he met them and invited them to Hickory Hill.

RC: You say that Kennedy’s wife included a copy of the Airplane single “White Rabbit” in the jukebox at Hickory Hill.

DG: Yes. I spoke with Grace Slick, and she was very happy to talk about it. Her take was, “Look, we didn’t really know if they ever listened to ‘White Rabbit.’ There’s a very good chance that it was just done because they knew we were coming over, and they were using us as a way to get to the youth vote. But we were happy to be used by Robert Kennedy; who better?” You know, he wasn’t necessarily quoting the lyrics! [Laughs]. But, nonetheless, it’s true, and they were there. This showed a certain level of awareness of other parts of the culture that most senators didn’t have.

RC: You also describe how President Kennedy crossed picket lines to see the film Spartacus, which was scripted by the blacklisted writer Dalton Trumbo. Would you agree that the Kennedys were, in many ways, well ahead of their time?

DG: Yes. I’m a fan of John Kennedy; I feel he’s been underrated by history. I mean, look, Chappaquiddick was a bad thing. And with John Kennedy, I’m sure the stories about his behavior with women are, to some extent, true. But as a political leader he’s really underrated when they do these ratings of the presidents. He was only in office for three years. But the fact that there was not a war over the Cuban Missile Crisis is such a monumental achievement, especially given that, from what I’ve read, the entire military wanted him to attack.

RC: The Joint Chiefs of Staff were encouraging him to launch a nuclear first-strike—but they didn’t realize there were over 160 ready-to-go nuclear warheads aimed at the United States from Cuba!

DG: Right. And on civil rights, he took steps, in terms of moral leadership, that Eisenhower was never willing to take. The Test Ban Treaty was also a big deal. No one knows what he would have done in Vietnam, but I believe he wouldn’t have done what Johnson did. After he died, his brothers were against the war. He had been to Vietnam as a young man; he knew that it was bullshit. And he’d already confronted the military; he wasn’t going to be pushed around by them. So, that’s what I choose to believe.

RC: The evidence leans heavily in favor of what you’re saying, because President Kennedy organized a major conference on the war that was held in Honolulu, shortly before he was killed, in order to lay the groundwork for pulling out of Vietnam. But again, that’s been suppressed by the media.

DG: Yes. There’s this whole revisionism of how great LBJ was. Look, he did some terrific things, largely because he had the legacy of the love for Kennedy and this wide margin of Democrats in both houses in Congress. He was a New Deal guy, and he wanted to do the right thing on those issues. But without John Kennedy, there is no Great Society. I think you’re right: Republicans in the right wing put a lot of energy into trying to tarnish Kennedy’s legacy, and they succeeded.

RC: Emmett Grogan and Peter Coyote, both members of the Diggers, took a malign view of the media’s effect on the counterculture, while Abbie Hoffman regarded it as a powerful tool to be exploited. Talk about the difference between the Diggers on the West Coast and the Yippies on the East Coast.

DG: The Yippies were influenced by the Diggers; there’s no question about that. Abbie Hoffman spent time with Emmett Grogan and Peter Coyote. A lot of the language, and the sense of theater, such as throwing money onto the Stock Exchange, was out of the Digger playbook of trying to create theatrical events in public that would illustrate a larger point. When I interviewed him for the book, Coyote was still complaining about it, even though he softened to the point of saying he did believe Abbie was a good person, and was compassionate, and trying to do the right thing. But he felt betrayed by the self-aggrandizement and the publicity-seeking ways of Abbie. The Diggers had this very austere, purist notion of what was righteous. They were obsessed with anonymity, they were obsessed with “everything should be free,” and they criticized almost everyone else who wasn’t a Digger. It’s hard to find anyone who was active in the counterculture that they had good things to say about, although initially they got along with the Black Panthers. The Panthers used the Digger’s mimeograph machine for the first issue of their newsletter.

Abbie hung out with the Diggers, but then he left them. They felt that, when he published Steal This Book, it contained a lot of their ideas but that he put his name and face on it. By all accounts, Emmett and Abbie hated each other. There are those who believe the Diggers were the real thing and the Yippies were posers, but I don’t agree. I respect the Diggers’ intellectual originality, courage, and commitment. They were on the cutting edge, particularly in the formation of the Haight-Ashbury community. But they also became bullies, and they were not open-minded about other people trying to work in different ways at the time. Abbie Hoffman was an egotist, and he did like attention, but he also had this sense of theatricality. His understanding of the media allowed me, as a teenager, to hear about these ideas. Thanks to his interest in McLuhan, and the media, and his commitment to communicating to the masses, Abbie reached people that the Diggers would never have reached. So, they both played their role, and neither of them was perfect.

In retrospect, I’m not a big fan of the protests at the Democratic Convention in Chicago in 1968. Although I could have gone, I had no interest in going. Ginsberg was against it, and Peter Coyote says that he also cautioned against it for reasons that are now clear. I do think that the Yippies meant well. But they got too intoxicated with their own drama to see how rapidly things were changing, and what the playing field was, and all that. I respect the Yippies, and I particularly respect Paul Krassner, who’s one of my favorite acquaintances, and who led an exemplary life. But again, I was more of a hippie, not a Yippie. I was always put off by the amount of anger that was in what they conveyed. Hoffman died tragically, and he had his issues, but he was an extremely positive force. They didn’t have any long-term vision, and they made some mistakes, but I think they were on the right side of things. But listen, Tom Hayden, coming from the nonpsychedelic, non-Digger influence of the left, was also there in Chicago. The Chicago Seven included Hayden and other SDS people. So, it’s not like the political radicals have more to be proud of.

RC: Was it a mistake to create this language of an “us” versus “them,” of “straights” versus “heads”? What’s the lesson to be learned from that today? I’m thinking of the politically correct jargon that’s alienated so many, on sides.

DG: Yes, this was one of the big mistakes. I certainly thought that way; I definitely wanted to know who was a “head” and who wasn’t. In those days “straight” meant not taking drugs; it didn’t have a sexual connotation. That there was “us” and “them,” and that they were “shallow”—that created resentment. Many felt left out of the party, and that helped fuel the divisions that we live with today, in this society. The language of many of those that I admired back then reinforced this idea: of dehumanizing what we called the Establishment.

Back then, to criticize civilization was morally correct, given the racism, materialism, and militarism. But to not recognize the good things about it was ridiculous. So yes, the “us” and “them” thing, the polarization, we contributed to it, those of us in the counterculture. Even the word “counterculture” says this. It contributed to the polarization, which led to the resentment of some of those that support Trump. I did an e-mail correspondence with Ram Dass about this, and his answers show that, clearly, he reached the same conclusion. He’s never shied away from thinking that LSD was a good thing, but he felt the polarization was counterproductive. And so, we have to try to heal the damage that was caused by this.

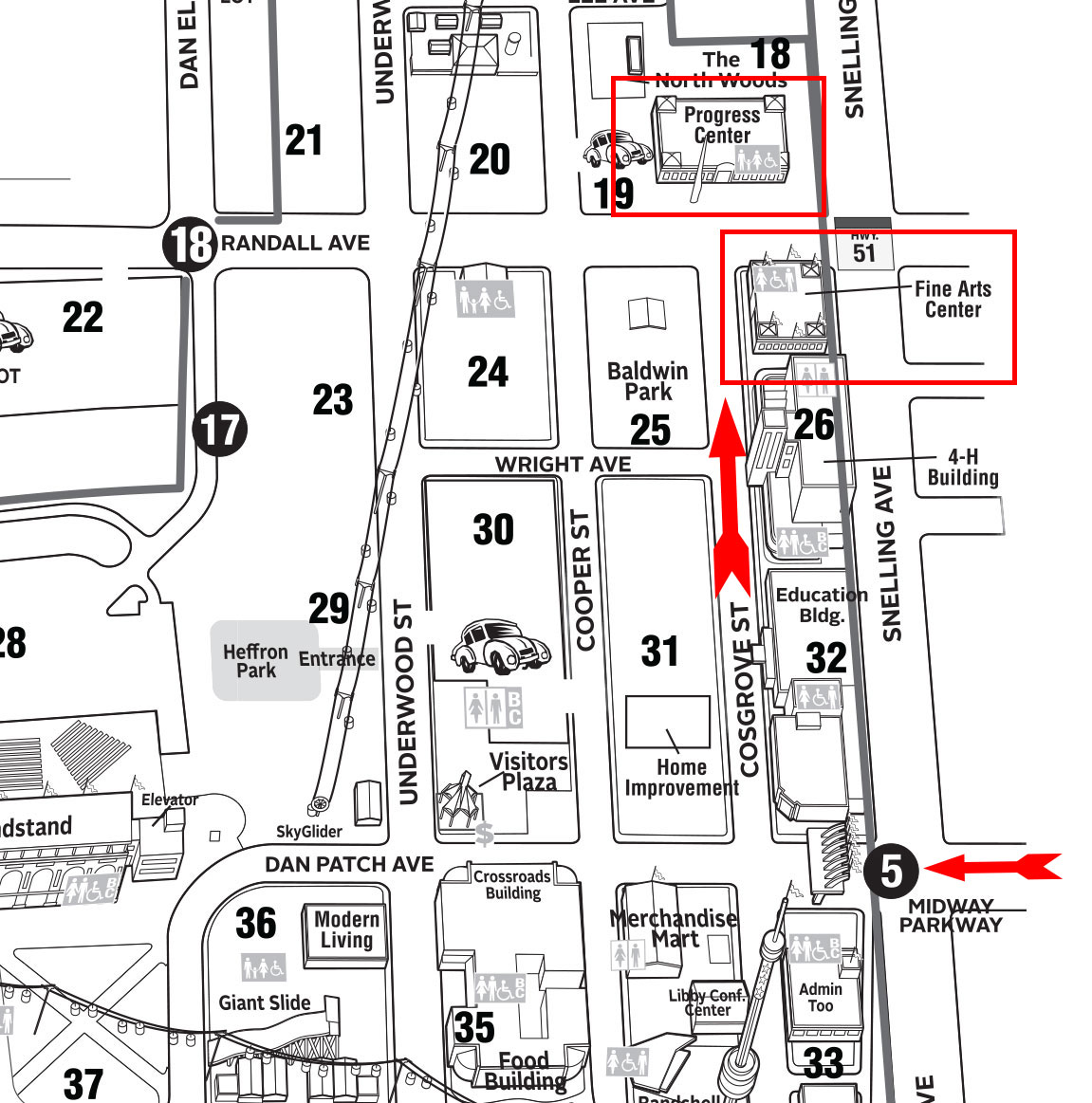

Click here to purchase In Search of the Lost Chord

at your local independent bookstore

Lisa Olstein

Lisa Olstein

Interviewed by Rob Couteau

Interviewed by Rob Couteau