What a Philosopher Is: Becoming Nietzsche

What a Philosopher Is: Becoming Nietzsche

Laurence Lampert

University of Chicago Press ($55)

Nietzsche’s Final Teaching

Michael Allen Gillespie

University of Chicago Press ($35)

Nietzsche’s Search for Philosophy: On the Middle Writings

Keith Ansell-Pearson

Bloomsbury Academic ($29.95)

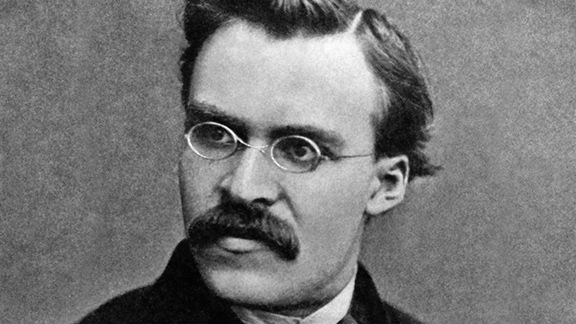

by Scott F. Parker

You might not know it from the recent and very public haranguing Steven Pinker delivered upon Nietzsche in his book Enlightenment Now, but more than a century after his death the “philosopher of the future” is every bit as studied and appreciated as he anticipated he would be.

Nietzsche, infamously, is one of those thinkers who can be made to say whatever one wishes. For one thing, his thinking underwent substantial revisions over the course of his writing; early, middle, and late Nietzsche regularly contradict one another in robust—Nietzschean!—language. For another, Nietzsche often favored an elliptical style that left it to the reader to connect the dots in his arguments, leaving himself susceptible to being taken out of context and used toward maleficent—or at least contrary—ends. “Most thinkers write badly,” he writes in Human, All Too Human, “because they tell us not only their thoughts, but also the thinking of their thoughts.”

These seeming ambiguities help explain the frequent misunderstandings of what Nietzsche’s writings mean. Sam Harris, generally more circumspect than this, has intimated on his podcast that Nietzsche is a proponent of nihilism and claimed that he is “irrelevant” to discussions of religion. Considering that the nihilism Nietzsche anticipated as a consequence of the loss of the religious worldview was among his most profound concerns and that his insights into the history and psychology of religion are among the most penetrating on offer, Harris proves to be as idiosyncratic in his thinking about Nietzsche and as superficial as Pinker, who finds Nietzsche’s anti-humanism culpable for “the megadeath movements of the 20th century,” thereby endorsing the Nazis’ own worst possible reading. Who, one wants to ask Pinker, has been more critical of nationalism and the herd mentality than Nietzsche?

But it is the sensitive reader whom Nietzsche most rewards. Thankfully, while Nietzsche is undergoing another of these periodic rounds of disparagement to which he has always been prone, scholars are reading his work carefully. We are right now amidst a spate of new monographs that bring sober and thorough attention to bear on Nietzsche’s project, ignoring the strawmen Harris, Pinker, and others make in his image.

In What a Philosopher Is: Becoming Nietzsche Laurence Lampert examines Nietzsche’s early writings through what he calls the first mature work—the fourth book of The Gay Science, known as “Sanctus Januarius”—in order to reveal the coherence of Nietzsche’s seemingly disparate projects.

In What a Philosopher Is: Becoming Nietzsche Laurence Lampert examines Nietzsche’s early writings through what he calls the first mature work—the fourth book of The Gay Science, known as “Sanctus Januarius”—in order to reveal the coherence of Nietzsche’s seemingly disparate projects.

Lampert’s method for telling this story follows two related tracks. The first is patiently scholarly. He writes, “Nietzsche’s thinking is a continuous development; what he advocates is discontinuous. The continuity he kept hidden in the workbooks is far more important than the discontinuity prominent in his books.” Readers might quibble here about what important means in this context—Nietzsche, for one, apparently did not understand it the way Lampert does. But reading the workbooks themselves does allow Lampert a convincing account of the continuity that is otherwise hidden. He shows, to take the most prominent example, that Nietzsche’s idea of the eternal recurrence of the same didn’t come from nowhere. It can be thrilling to see Nietzsche’s ideas contextualized this way, their coming to be documented exactingly—but a little goes a long way. Lampert’s recountings, detailed to the exclusion of all possible doubt, come across as excessive at times for the non-specialist reader.

The second, related, track Lampert takes to get Nietzsche to cohere follows what the philosopher himself set about to prove with the forewords he added to his earlier works after writing Thus Spoke Zarathustra, the first book of Nietzsche’s final phase—and the one that changed everything for him. In those forewords, Nietzsche reads his early books as necessary steps on his journey toward becoming the philosopher that with Zarathustra he became. By Lampert’s reading, “what drove him from the start, [was] the need to understand the Philosopher and the Artist in the context of modern culture.” We can see Nietzsche’s first attempt at an understanding in his early writings about (and deference to) the respective representative figures Schopenhauer and Wagner, the two looming influences from under whose shadows Nietzsche would emerge to enter, first, his Enlightenment-influenced middle period (about which, more below) and, eventually, his third, or “mature,” period. It is in the mature period, beginning with “Sanctus Januarius” (which Lampert dubs “a January of a Book, ending an old ‘year’ of human achievement and opening a new ‘year’ in Nietzsche’s work and beyond”), that Nietzsche is able to get a fix on the two types—an understanding made possible by his most profound idea and the conditions that allowed it: “Nietzsche became what he was as a philosopher and an artist during the hard summer of 1881, when his sickness granted him enough good days to take his daily six-to-eight-hour walks and gain his most fundamental insights and compose their fitting sentences.”

Picking up where Lampert’s account leaves off, Michael Allen Gillespie, in Nietzsche’s Final Teaching, treats Nietzsche’s theory of “the eternal recurrence of the same” as the linchpin of his mature philosophy. Gillespie argues that this idea, which first struck Nietzsche in 1881 as he walked around Switzerland’s Lake Silvaplana, resolved the questions that had preoccupied Nietzsche before 1881 and that orient all of his writing until his breakdown in 1889.

Picking up where Lampert’s account leaves off, Michael Allen Gillespie, in Nietzsche’s Final Teaching, treats Nietzsche’s theory of “the eternal recurrence of the same” as the linchpin of his mature philosophy. Gillespie argues that this idea, which first struck Nietzsche in 1881 as he walked around Switzerland’s Lake Silvaplana, resolved the questions that had preoccupied Nietzsche before 1881 and that orient all of his writing until his breakdown in 1889.

Most of us, stuffed with common sense, look askance at Nietzsche’s theory of eternal recurrence. It strains against our modern worldview even to consider it. Time is a loop? All of this repeats forever? How do we not but continue from there: Nietzsche was a bit of an eccentric, wasn’t he? Let’s appreciate his wit and style, let’s draw on his criticisms of Christianity, let’s acknowledge his contributions as a psychologist. But eternal recurrence—are we meant to take that seriously?

Gillespie takes it very seriously indeed. As he explains, Nietzsche thinks that eternal recurrence offers an escape from the meaningless and nihilism that follow the death of God. But only if one can affirm all things absolutely, by what Nietzsche calls amor fati. Unlike Faust, who affirms one moment, for Nietzsche eternal recurrence means that “in order to truly will any one thing, it is necessary to will all things.” It is this willing of the whole that makes each moment meaningful: it is vital.

The eternal recurrence establishes what Gillespie calls Nietzsche’s “(anti-)metaphysics”; it provides the ontology that coordinates what we can recognize as a corresponding anthropology, theology, cosmology, and logic, each drawn from Nietzsche’s most enduring ideas of the 1880s (the Ubermensch, death of God, will to power, and perspectivism, respectively). Of these, it is the logic in Gillespie’s account that is the awkwardest fit. Gillespie’s own writing demonstrates that a rational account of Nietzsche’s worldview is possible and that offering it can eliminate much of the ambiguity that otherwise attends. The rub, though, is that as clear a writer as Gillespie is, there is only one Nietzsche.

Gillespie shows how Twilight of the Idols and Ecce Homo, two works of 1888, are structured as sonatas and advance a musical rather than rational logic. Nietzsche’s “fusion of image, emotion, and form” in this period constitute what Gillespie calls “a mosaic of words”—or, as Nietzsche has it, “each word streams out its strength as sound, as place, as concept, to the right and left and over the entirety.” This is not, obviously, how we’re used to reading philosophy. It is also, again, why we love to read Nietzsche (and to a significant extent why we sometimes struggle to interpret him).

Even if “Nietzsche’s goal is not to persuade but to enthuse, entrance, and overpower the reader, to initiate him into sacred mysteries and impel him to action,” the question remains: to what end? Gillespie’s list of the thinkers and movements inspired by Nietzsche is too long to quote here. This consequence is due as much to what Nietzsche’s corpus doesn’t say as it is to how he says what he does. Gillespie argues compellingly that all of Nietzsche’s writings after his 1881 walk at Lake Silvaplana build toward a magnum opus—a thorough articulation of the eternal recurrence of same—that was precluded by Nietzsche’s collapse in 1889.

The eternal recurrence—Nietzsche’s “deepest thought”—is the hollow core around which the rest of his project orbits unsteadily. One open question is whether Nietzsche could have completed such an account if he had remained lucid. We might wish he’d completed the project so we’d have an easier time accepting or rejecting and preventing it from being adopted willy-nilly. But as we should expect, Nietzsche was up to something subtler than a naive naturalism. As Gillespie explains,

Nietzsche does not present the eternal recurrence as an absolute truth, but as a perspective, a perspective that is affirmed not because it is true or false but because it is most life-enhancing. Indeed, from Nietzsche’s point of view, we cannot possibly know whether it is true or false. To affirm the doctrine is rather an act of the will and means adopting a stance toward life that treats the doctrine as if it were true, and that consequently eschews all negation, affirming every possibility not merely as possible but as necessary. Affirming the eternal recurrence in this sense does not entail the rejection of any path or way of life, and indeed requires affirming them all.

This is a pragmatism of meaning, and it’s one Nietzsche adopted personally before extending publicly. Nietzsche “became convinced not only that he had a task that could give meaning to his life, but that this task was of world-historical importance . . . His task, he came to believe, was nothing less than the revaluation of all values, the complete transformation of European civilization.” The nihilism that he had confronted following the death of God was the nihilism that was bearing down on Europe. This is the neat circle of Nietzsche as destiny that eternal recurrence demands. Once he recognizes the problem, he becomes the (possible) solution. “Nietzsche thus claims that he is a destiny not because he wants to be but because as part of the unfolding of all things he is the moment in which the whole affirms and wills itself, the moment of the appearance of the god who in his eternal birth and death wills the constant renewal of the whole.” His destiny is to write the books that will bring about the future. In so doing he has so done. The texts perform themselves.

Nietzsche’s Final Teaching suffers slightly as a collection of stand-alone essays that repeat themselves—rather blatantly sometimes. But this is a small price for the reader to pay for such a resounding synthesis of Nietzsche’s later work. Gillespie makes an admirable attempt at completing the picture that Nietzsche didn’t.

Compared to the well-known works of Nietzsche’s “mature” period, his middle period has historically been given short shrift. For Lampert this relative neglect is warranted; the middle period represents for him a necessary failure. While Things Human All Too Human (Lampert’s preferred translation of the title) represents an important shift for Nietzsche away from his deference to Schopenhauer and Wagner, Lampert instructs that we “think of his first book on the free mind as erring in the modern way, deferring to Enlightenment orthodoxy as if that were true free-mindedness; treat it with the suspicion its deference deserves; count it too among the works in which he was not yet himself.” So a failure, but a necessary one: the free-mind books (Human, All Too Human; Dawn; and The Gay Science) allowed him to grow through his deference by requiring “the Enlightenment to perform intelligent surgery on itself: slice away that part that would consume its most valuable part; its mind, its Greek-science root, must cut away what seemed its heart, its Christian root.” Through this period lies what Nietzsche has always pursued: truth and an individual strong enough to bear it.

Again we see Lampert here following Nietzsche’s lead. Human, All Too Human is the book Nietzsche would come to see as a failed introduction to Zarathustra and which, before his idea for the Forewords Project, he wanted to destroy. In Nietzsche’s Search for Philosophy, Keith Ansell-Pearson takes a very different approach to this period. Reading the books not as gates to be passed through on the way to the real Nietzsche but as valuable works in their own right, Ansell-Pearson finds the middle period to be a success—possibly the high-water mark—for Nietzsche.

The core argument of Nietzsche’s Search for Philosophy—that we should not ignore the middle period—is impossible to disagree with. Ansell-Pearson’s discussion of the works in question describe a thrilling series that readers will likely find themselves inclined to consult directly. This is an inevitable challenge with Nietzsche: he provokes myriad responses, all of which suffer by comparison to their source. It is perhaps this way for all truly original writers. A critic can be inspired by Nietzsche to his highest articulation and still be just a critic. Ansell-Pearson himself is “mindful of Lawrence Hatab’s warning that when we ‘translate’ Nietzsche into our professional philosophical agenda, we do what must be done, but in so doing we bring to ruin something special and vital. . . . It seems we must ‘murder to dissect.’”

The core argument of Nietzsche’s Search for Philosophy—that we should not ignore the middle period—is impossible to disagree with. Ansell-Pearson’s discussion of the works in question describe a thrilling series that readers will likely find themselves inclined to consult directly. This is an inevitable challenge with Nietzsche: he provokes myriad responses, all of which suffer by comparison to their source. It is perhaps this way for all truly original writers. A critic can be inspired by Nietzsche to his highest articulation and still be just a critic. Ansell-Pearson himself is “mindful of Lawrence Hatab’s warning that when we ‘translate’ Nietzsche into our professional philosophical agenda, we do what must be done, but in so doing we bring to ruin something special and vital. . . . It seems we must ‘murder to dissect.’”

Nevertheless, the Nietzsche that Ansell-Pearson reveals is curious, grounded in science, and committed to his pursuit of moderation and sober thinking. But even in his Enlightened mode he is never simplistic. It’s easy to forget that when his madman delivers the news of the death of God in The Gay Science, one of the things Nietzsche is up to is criticizing “the village atheists . . . [who are] too easily satisfied with a secular materialism.” Pinker, Harris, and our other own village atheists might do well to give this Nietzsche another read.

One of Nietzsche’s fundamental insights from this period, to which Ansell-Pearson ably draws significant attention, is into the fetishization of truth as a substitution of one god for another. Inspired as he is in this period by Epicurus, Nietzsche pursues naturalism insofar as it is conducive to a “full and excellent life.” Metaphysics, in other words, is subordinate to ethics—and, for Nietzsche, to aesthetics too. “Gay scientists are ‘too experienced, too serious, too merry, too burned, too profound’ to have belief in a simple-minded love of truth.” Philosophy, for Nietzsche in his middle writings, is not a matter of articulating correct views on things. It is “a set of practices or exercises that seek to transform one’s way of life, indeed, one’s entire way of being and fundamental orientation in the world.”

Ansell-Pearson, along with Lampert and Gillespie, reminds us that Nietzsche has plenty to say to our time and to many of our conversations, if only we have ears to hear him. Likewise, these three books remind us that nuanced writers demand careful readers.

Gary Shteyngart is the New York Times bestselling author of the memoir Little Failure (a National Book Critics Circle Award finalist) and the novels Super Sad True Love Story (winner of the Bollinger Everyman Wodehouse Prize), Absurdistan, and The Russian Debutante’s Handbook (winner of the Stephen Crane Award for First Fiction and the National Jewish Book Award for Fiction). His books regularly appear on best-of lists around the world and have been published in thirty countries.

Gary Shteyngart is the New York Times bestselling author of the memoir Little Failure (a National Book Critics Circle Award finalist) and the novels Super Sad True Love Story (winner of the Bollinger Everyman Wodehouse Prize), Absurdistan, and The Russian Debutante’s Handbook (winner of the Stephen Crane Award for First Fiction and the National Jewish Book Award for Fiction). His books regularly appear on best-of lists around the world and have been published in thirty countries.