Roberto Calasso

Roberto Calasso

translated by Richard Dixon

Farrar, Strauss and Giroux ($20)

by M. Lock Swingen

In conferences and symposiums, Roberto Calasso, one of the preeminent men of letters living and working in Italy today, can sometimes be heard to describe the tradition of literature as a kind of living creature, a veritable “serpent of books” winding its way through the centuries and epochs, wholly engulfing cultural periods, places, personalities, criticism, philosophy, and myth. The interlinking vertebrae are forever multiplying and rearranging as the serpent devours its way through time and space, but in Roberto Calasso’s magnum opus, a series of interconnected volumes that he began with The Ruin of Kasch in 1983, the Italian man of letters aims to dissect and study the anatomy of this living creature during some of its most crucial perambulations through our collective history. Although the encyclopedic series of volumes in Calasso’s oeuvre take on wildly different subject matter—Greek mythology, classical Indian philosophy, and pagan imagery, to name a few—they uniformly share a method and style that is the trademark of Calasso’s art form: Each volume is made up of a densely layered pastiche of citations and quotations, genealogical studies of philosophical ideas and concepts, epigrams and aphorisms, and penetrating character profiles of the writers and thinkers whose work defines a time period. Richard Dixon’s recent translation of The Ruin of Kasch reintroduces the remarkably erudite and genre-defying universe of Roberto Calasso to a younger generation of English readers who are perhaps unfamiliar with his work.

The heterogeneous and ever-revolving cast of thinkers, artists, and hangers-on who populate the brimming pages of The Ruin of Kasch circle around the three foremost subjects of the book: ritual and ancient sacrifice, revolution, and the origins of modernity. Significantly, Calasso has chosen the historical figure of Talleyrand, the crafty French statesman and diplomat who managed to hold onto his head during the French Revolution, as guide and interpreter designated to lead the reader through the thick and gnarly pages of Calasso’s labyrinthine tome. Possibly, Talleyrand also provides the key that unlocks the interrelatedness of the daunting subject matter, if they are indeed interrelated, which proves a constant and nagging question that confronts the reader at almost every turn of page. Prepare for detours and forays that follow no discernible trail. Just shy of 400 pages, Calasso manages to quote everyone and everything from Baudelaire, Goethe, the Upanishads, “Das Kapital,” the German anthropologist Leo Frobenius (from whose collation of African myths the title of the book is drawn), and several hundred other works in several languages. If books had a maximum capacity of weight and persons like elevators do, The Ruin of Kasch is definitely breaking code. Calasso’s principle model, the German critic and literary theorist Walter Benjamin, once aspired to write a book that consisted of nothing but quotations. Calasso has very nearly achieved just that.

The book opens during the French Revolution, that classic episode of modern history, where the collapse of the ancien régime presented the downtrodden and oppressed an unprecedented opportunity to take control of their circumstances and refashion them according to a conscious plan or set of principles. Nobody before in history had ever had such an extraordinary chance. The absolute monarchy was overthrown. The nobility were overthrown. The Catholic Church was shuttered up. In the middle of all of it we find Talleyrand. Calasso writes: “Talleyrand’s role above all was that of master of ceremonies—but this was an age where ceremonies had lost their meaning, an age that claimed it could do without them, while it stumbled at every step. At that point Talleyrand offered his arm, impassively—and helped find a way out of the embarrassment. But what ought to have caused alarm was his distant gaze in proffering help.” Calasso’s uncanny ability to uncover the true character and significance of historical figures derives from the vast source material that he unearths and wields with the ease of a scholar, but his aims are never academic despite all his learning: Calasso instead wants to reveal character like a novelist. For example, while comparing and contrasting the two historical figures of Talleyrand and Lafayette, which Calasso sets up as a kind of dramatic foil in one passage, he writes:

Lafayette is the true opposite of Talleyrand. They are born and die within a few years of each other, both have illustrious ancestries, both are involved in everything. Lafayette, convinced from the very start that he is moving with the times, is especially eager every now and then to strike historic poses, and in the meantime to survive. He has an unshakable capacity not to notice. Talleyrand also moves with the times, follows trends, changes his shirts and his allegiances. But this is not why he is not forgiven. On the contrary: it is felt that his amorality is consistent and faithful, that his ever-moving and restless waters conceal some solid, ancient rock that resists the ravages of time much better than the papier-mâché of Lafayette.

Of course, the transition phase from the ancien régime to the new order wasn’t a pretty one, to put it mildly. The euphoric liberation initially felt by the downtrodden and oppressed led eventually to what is infamously known and aptly named as the “Great Terror,” a time period characterized by the vacuum of power ushered in by the total collapse of the ancien régime and the subsequent frenzied power grab, where beady-eyed and murderous tyrants and opportunists competed ruthlessly for supremacy. Enter Robespierre, another heavy hitter during the French Revolution. The line between political opposition and treason blurred. Political crimes now became so widely defined that nobody felt safe. The former nobility and just as many revolutionaries were now being executed for their counter-revolutionary potential alone. Exit Robespierre. Many were shot or drowned, but most died under the instrument that would eventually dispatch the king: the guillotine. Introduced in April 1792 and designed as a humane means of execution by rational men who touted the progressive policies and ethos of the Enlightenment, the guillotine unleashed rivers of blood and claimed an unprecedented number of sacrificial victims unseen in that era. It is this necessity for government and order by bloodletting that leads us to the mythological tale at the heart of The Ruin of Kasch.

Calasso recounts the tale of a prosperous African kingdom that lends its name to the title of Calasso’s book—Kasch—where the king reigned supreme but where an order of priests would also consult the stars and according to the course of those stars calculate the hours and pronounce judgements and sometimes order the execution of the king and the installment of a new one. The king would also choose companions to die with him. In the tale of “The Ruin of Kasch” the king chose a famed storyteller named Far-li-mas to accompany him to his death. One day, the king invited Far-li-mas to the court to recount his stories and fables. Calasso writes: “Far-li-mas’s story was like hashish. When he had finished, all were swathed in a benign unconsciousness. King Akaf had forgotten his thoughts about death. None of those present had realized that Far-li-mas’s story had lasted from the evening to the morning.” It went on like this for some time, joyfully. But the priests also kept a fire upon which they would heap the keepers of the fire as sacrificial offerings to God. One day, the sister of King Akaf was appointed the keeper of the fire. Sali-fu-Hamr was very afraid and did not want to die. Sali also loved Far-li-mas and did not want him to die. Sali also loved her brother the king and did not want him to die. But the calculation of the course of the stars according to the priests ordained it. In the tale of “The Ruin of Kasch” Sali confronts the order of the priests. She says:

“Great are the works of God. But the greatest of them is not his writing in the sky. The greatest of them is life on earth. I came to realize it last night.” The priest said: “What do you mean?” Sali said: “God has given Far-li-mas the gift of telling stories, as he had never done before. This is greater than the writing in the sky.” The chief priest said: “You are wrong.” . . . Sali said: “Then show me I’m wrong, that the writing in the sky is more powerful and greater than life on earth.”

The conflict between the priests and Sali is interesting here. For a modern reader, it isn’t very difficult to understand the motivation of Sali: Who the hell wants to be sacrificed? Clearly, there is a sharp line drawn between the protagonist and the bad guys here. But is it really so? We need to consider the time period. After all, it’s not like our ancestors didn’t know what they were doing. In early settled agricultural societies like the land of Kasch there permeated in the people an extreme sense of dread and fear over man’s tenuous place in the natural order. In contrast to the lifestyle of bygone nomadic hunter gatherers, the people who settled down to build and to plant began to experience the natural world as an endless source of chaos and terror. Gone were the days of following the rhythmic provisions of nature, like the hunter gatherers did, where there was always enough food over there if there wasn’t enough food over here. To say the least, that level of trust in nature’s merciful bounty was completely absent in the early settled agricultural societies, where a living had to be tortured and coaxed out of a specific piece of real estate. Imagine trying to predict the time for planting, for harvesting, for when the frost will set in or when the rains will come or when the river is going to flood the plain. Anxiety becomes a way of life. Planting a month late one year could lead to the collapse of an entire civilization.

One of the most striking similarities among early settled agricultural societies in this regard is the emergence of the awareness of the heavenly bodies and the course of the stars and the establishment of a priesthood dedicated to tracking those movements of the night sky. This desire to interpret and even potentially control the environment is almost entirely absent from hunter gatherers, who of course understood the environment astoundingly well, but they did not seek to control it. At first, the priesthood still understood the natural forces in terms of an omnipotent will that drove events and brought joy or catastrophe. Basically, they took everything personally. But the priesthood eventually made a tremendous discovery. They discovered that you could bargain with the future. If you let go of something valuable or even something that you hold most dear that sacrifice would grant you a moral claim that you could redeem in the future. In other words, the discovery of sacrifice is the concession that something valuable has to be given up in order for something even better to happen later on. One must embrace sacrifice and death voluntarily in order to move forward and progress. Hence all that burnt lamb smoke and all those firstborns tied to posts.

But Sali thinks the land of Kasch has progressed beyond the need for all the bloodletting and all the sacrifices. And she does have a point here. One of the ways to mark and identify the development of early settled agricultural societies is by tracking the maturation and increasing level of mastery displayed in the calculations of the heavenly bodies and the course of the stars in the night sky. The priesthood began to arrive at the understanding that there existed some kind of impersonal, mechanical order to the universe that ran like clockwork. They began to map out their earthly territory in less personal terms. If the priesthood had developed progressive means that allow society to take possession of the environment, why sacrifice to God? In the land of Kasch the crops are always planted on time. When the priesthood arrives at the court to listen to the stories of Far-li-mas, Calasso writes:

As morning approached Far-li-mas raised his voice. . . . The more powerful his voice became, the more its sound echoed in the people. The hearts of the people rose against each other, as in battle. They raged against each other, like the clouds in the sky on a stormy night. Flashes of anger clashed with thunderbolts of fury. When the sun rose, Far-li-mas reached the end of his story. The confused minds of the people were overwhelmed with indescribable amazement. For when those still alive looked around them, their eyes fell on the priests. The priests were lying on the ground, dead.

From that day on no one else was killed or sacrificed in the land of Kasch. Calasso goes on to recount that King Akaf lived happily to the end of his days, when he died of old age. Far-li-mas succeeded him as king. Wise men came to seek the new king’s advice and counsel. All the princes from foreign lands sent Far-li-mas gifts. But the success and achievements of the land of Kasch sowed envy in the hearts of the neighboring lands and kingdoms. When Far-li-mas died the neighboring lands and kingdoms broke their treaties and began a war. The war marked the ruin of the land of Kasch.

Sacrifice, Calasso writes, “is the cause of ruin,” but also, “the absence of sacrifice is the cause of ruin.” After recounting the mythological tale of “The Ruin of Kasch,” squirreled away somewhat inconspicuously in the middle of the book, Calasso then runs through an exhaustive and sometimes baffling gloss of the tale’s possible meanings but also the possible meanings of the nature of sacrifice itself. One of the theories of sacrifice that grips Calasso’s imagination is the theory of the scapegoat, formulated by the social scientist and philosopher René Girard. Girard theorized that when disagreement and discord threaten to tear apart the delicate social fabric of a community, one of the methods through which the people restore order and harmony is by designating an outside party or victim onto which everyone in the community can direct their rage and antipathy. Usually, a totalitarian ruler prescribes the outside party or victim whom also not-so-coincidently justifies the totalitarian ruler’s own rise to absolute power. It’s a sort of three step process. Citizen 1: “I’m going to kill you.” Citizen 2: “Please don’t kill me.” Citizen 1 and Citizen 2, intermediated by totalitarian ruler: “Well, let’s all kill them then.” The subsequent discharge of violent energy that had been heretofore bouncing around the community reaffirms a cathartic feeling of collective identity. It works like a charm almost every time. Calasso quotes Girard directly on the obvious drawback of this formula: “This is the terrible paradox of desires in men. They can never agree on the preservation of their object; but they can always agree on its destruction; they never reach agreement with each other except at the expense of a victim.”

This problem brings us to the last great subject of The Ruin of Kasch: Calasso’s very subtle polemic against modernity, which was ushered in by the turmoil and monumental bloodshed of the French Revolution, the harbinger of our modern political landscape. Essentially, Calasso’s argument is that the disorder of the contemporary world is a legacy of the collapse of earlier societies in which the ritual of sacrifice played a crucial role. Calasso writes: “History can be summed up as follows: for a long time men killed other beings, dedicating them to an invisible object; and then, from a certain point, they killed without dedicating this act to anyone . . . Then the simple act of killing remained.” What, then, was the real significance of all those rolling heads during the French Revolution? There were so many of them leveled at the scaffold of the guillotine. It is difficult sometimes not to wonder if the revolutionaries ever came to regret the brutal efficiency of that machine. Do all those tumbling heads embody something like the tremendous realization of the priesthood in “The Ruin of Kasch” that one must sacrifice the old ways of doing things in order to move forward and progress? Or do they perhaps represent the killing of the priests themselves? Or were they merely those poor sacrificial victims à la Girard that crudely held the community together in a time of crisis? It is a question that haunts the formidable mind of Calasso. Since 1789, in any case, few countries have failed to experience their own revolution, and in all of them there have been revolutionaries and counter-revolutionaries looking back at what exactly happened in France in the hopes of finding inspiration, models, patterns, and warnings. In the thick and gnarly pages of The Ruin of Kasch Calasso contemplates the prophecy of the guillotine more seriously and more thoroughly than perhaps anyone else living today.

In the most revealing gloss of the mythological tale of “The Ruin of Kasch” Calasso writes succinctly: “This is a story about the passage from one world to another, from one order to another—and about the ruin of both. It is the story of the precariousness of order: of the old order and the new. The story of their perpetual ruin.” (139). Of course, he could just as well be talking about the French Revolution—or the inheritors of it, whom would be us—and that struggle since time immemorial between the values of tradition and the relentless forward march of progress. And yet in all that chaos and pandemonium of 1789 there was one man who rose above it all, almost effortlessly: Talleyrand. No matter how tangential or free-wheeling the pages of The Ruin of Kasch become, and they do become pretty damn oblique and sometimes even schizoid in their unyielding digressions, they always seem to curb back inevitably toward the historical figure of Talleyrand, the center of gravity in the expansive universe of Calasso’s mind-bending tome, where data and information and analysis is always whirring past the reader at the level of warp speed. In the end, why did Calasso choose Talleyrand to guide us Virgil-like through the overflowing pages of The Ruin of Kasch?

The answer, surprisingly enough, seems clear. Talleyrand was the only political figure who was able to leap frog from one regime to another and another during a time when most other political figures had their heads rolling on the scaffold whenever a regime change occurred. Widely detested for his cynicism and duplicity and extremely useful for the same reasons, Talleyrand held positions of power through the ancien régime, the French Revolution, the Directory (the constitutional republic until Napoleon seized power), Napoleon, the Bourbon Restoration, and finally during the return of the citizen-king Louis-Philippe. “While every municipal partisan spirit was at last finding his metaphysics in the vision of the Party,” Calasso writes, “Talleyrand maintained the indifference of the sky and the water: mutable, elusive, unscathed among many faiths.” For Calasso, Talleyrand perhaps represents the essential problem posed in the dense pages of The Ruin of Kasch: How do we know who to sacrifice if the art of politics is now about surviving the grip of events? Clearly, it is precisely the evasive fluidity of Talleyrand’s politics that makes him the first true modern man of our time.

Click here to purchase this book

at your local independent bookstore

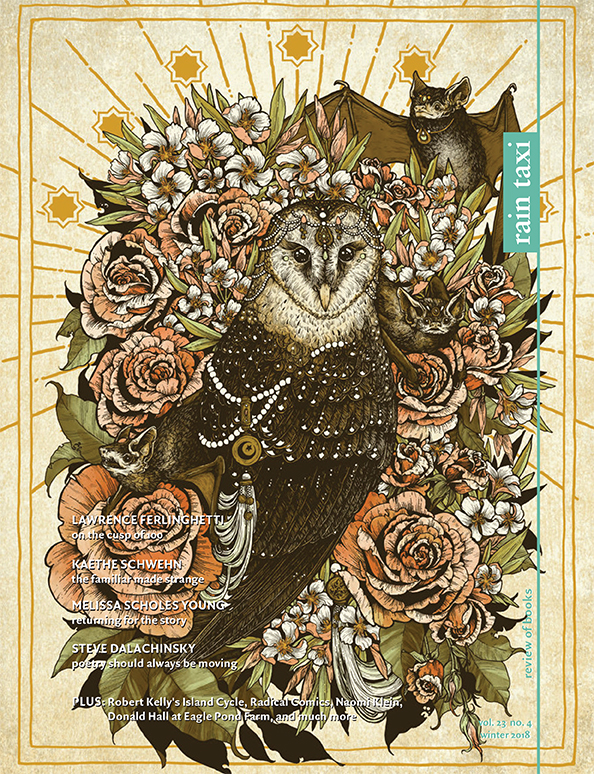

Erica Williams is an illustrator and cute things addict in Minneapolis, MN. She is known for intricate mark-making and illustrations of flora and fauna with macabre tones, as well as custom typography and screen printed posters. Much of her work focuses on the forgotten, endangered, lore, myth, and the occult. Erica really adores her cats and tries to incorporate the reverence she feels for nature and the world around her into her work while honoring mortality. See more of her amazing work at

Erica Williams is an illustrator and cute things addict in Minneapolis, MN. She is known for intricate mark-making and illustrations of flora and fauna with macabre tones, as well as custom typography and screen printed posters. Much of her work focuses on the forgotten, endangered, lore, myth, and the occult. Erica really adores her cats and tries to incorporate the reverence she feels for nature and the world around her into her work while honoring mortality. See more of her amazing work at