Interviewed by David Wilk

Family history for so many contemporary Jews is fraught. Most of us have relatives who disappeared without a trace, except for scattered entries in German records of extermination. Some fewer of us have had living relatives whose lives were defined by the Holocaust, almost always in horrific and devastating ways.

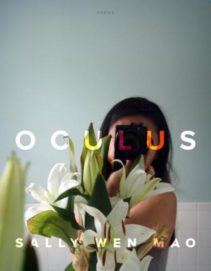

Bram Presser, an Australian writer, spent eight years working on an unusual novel, The Book of Dirt (Text Publishing, $15.95). It is a compelling story that explores the real-life events of Presser’s Czechoslovakian grandfather, Jakub Rand, from the 1920s through the Holocaust and into his post-War life in Australia. Combining family stories with archival research and interviews, Presser addresses the complexities of this history with the only tool that could possibly make sense of it—imagination.

The relatively large number of characters and the movement between places can be confusing for the reader, but Presser’s grandfather, his grandmother Dasa Roubicek, and their immediate family give the book focus. More importantly, their story of survival shines through the immense amount of pain and suffering through which they lived.

You do not need to be Jewish to find this novel compelling and powerful. All of us can relate to what it means to find hope in the worst possible circumstances, and anyone can find compassion for how the descendants of survivors of terror must try to understand the stories of their forebears. Readers will find The Book of Dirt to be a wonderful and transformative literary work.

Born in Melbourne in 1976, Bram Presser has been a punk rocker, an academic, and a criminal attorney. He writes the blog Bait for Bookworms and is a founding member of Melbourne Jewish Book Week. His stories have appeared in Vice Magazine, The Sleepers Almanac, Best Australian Stories, Award Winning Australian Writing and Higher Arc. In 2011, he won The Age Short Story Award.

David Wilk: This is an amazingly painful book in a lot of ways for people like myself, who like you had family members who did not survive the Holocaust. We probably should say that you call this book a novel, even though it’s hard to tell the difference between autobiography, memoir, and novel here, because that gives you the freedom to imagine, and to enter the lives of people.

David Wilk: This is an amazingly painful book in a lot of ways for people like myself, who like you had family members who did not survive the Holocaust. We probably should say that you call this book a novel, even though it’s hard to tell the difference between autobiography, memoir, and novel here, because that gives you the freedom to imagine, and to enter the lives of people.

Bram Presser: Yeah, and also where there aren’t records or where I don’t have hard evidence where I have to fill the gaps, it would be disingenuous of me to claim otherwise. I was really interested in what their experiences were, and I think you don’t get that from records. You don’t get that from seeing a train schedule or something like that.

At the beginning, I really didn’t have anything to go by. Though I had kind of an idea of what their stories were, I found that I had to turn to fiction to actually get to know them. I just felt that there was a different truth, a deeper truth in fiction than there would’ve been in it being a historical work, a biography or autobiography.

DW: I’ve read many memoirs of people who survived the Holocaust, and I think that it’s different for them; their imaginations are no longer capable of functioning because of the horror and the sheer destructiveness they lived through.

BP: Absolutely, and I think that the purpose in writing it is different as well. I’ve also read so many, and I think firstly they’re offering testimony. They’re bearing witness, which is an incredibly important thing to do, and so imagination doesn’t necessarily play into it. They are the ones who lived this horror that we can’t imagine, and I think they need it documented for their own sake, and for the sake of humanity.

DW: Whereas, your perspective is different. You’re living today. You’re the descendant, and you’re trying to place yourself in their history to create your own, and that is a different thing than to tell a story of what happened to you.

BP: Yeah, at the end of the day, I’m making sense of my own existence. I’m the beneficiary of their horrific experience and survival. All the stuff that’s coming out now about inherited trauma and what have you, that is part of my inheritance, and to understand that, I have to go into their lives and try to make sense of them.

DW: They’ve talked about trauma actually affecting the genetic makeup and being passed on through generations, which actually does make sense.

BP: Absolutely, and for me, it’s strange because Melbourne, where I come from, had the highest per capita Holocaust survivor intake after Israel.

DW: Why was that?

BP: Well, you ask most of the survivors and they say it was the furthest place they could possibly think of from Europe, and they’re right. Australia is out in the middle of nowhere.

DW: So, I don’t want to parse through the book to try to figure out what is true and what isn’t, but to build the groundwork for how you got there: Jakub Rand, he’s a real person?

BP: Yes, he was my grandfather.

DW: I love the beginning where you go through the locations where they lived. I know my own grandparents talked about where they were from, and I always took it as a received wisdom that they were from Hungary, but when I looked at the place where they actually were from, it’s not Hungary. It just happened to be part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire at that time.

BP: Right. I actually wanted to visit the place, it’s on the foothills of the Carpathian Mountains somewhere. This is years and years ago, so it’s my grandfather’s brother and he said, “Maybe you could’ve gone there.” Now it’s abandoned and it’s surrounded with brigands and thieves and people who will attack you on the road, and he goes, “You just can’t go there, if you can even find it.”

DW: That’s so weird.

BP: I know. What’s the weirdest for me is that at the time that my grandfather was born and during his childhood, it was a reasonably vibrant small village, perfectly accessible from the nearby cities and what have you, and now it’s at best a field.

DW: Right, although as you suggest, he desperately wanted to leave this small town.

BP: Oh, very much so. It’s quite funny because he was born into a religious family. He was the son of the rabbi of that village and he was sort of the golden boy who was going to be the next rabbi, and by the time he was a teenager he was not at all interested in it. He wanted to see what the wider world had to offer so he fled to Prague in search of a secular education. I think he probably came with letters of recommendation or something like that because he was adopted very quickly into the Prague religious community. So, I don’t think he was as unknown as I necessarily make out in the book, but at the same time, I’ve got no evidence one way or the other so it could’ve been that he was just someone that turned up, they liked the fact that he was quite learned and interested in learning, and he kind of had a foot in each camp. On one side, he was part of the religious community, but on the other side he was pursuing secular education at Charles University.

DW: Again, we don’t need to go through the whole story here, but it’s sort of amazing some of the things that happened to him . . . Even as you imagine it, just the act of being a survivor in itself is pretty amazing.

BP: Yeah, the question I get asked most is, “How much is fact? How much is fiction?” Most of it is a dramatization of anecdotes that I heard that are to the best of my knowledge true.

DW: Right, as told, as remembered, it’s true, because we don’t know.

BP: But it’s not stuff that I made up out of the blue.

DW: It feels like the structure of the story is all based in acknowledgeable fact, but as you’re trying to track back and figure out what really happened, you get these kind of mixed reactions like, “That couldn’t have happened. That’s not real.”

BP: I actually still remember walking into Yad Vashem, the main Holocaust museum in Israel. The camp my grandparents were in, Theresienstadt, I remember going there and I had this story in my head: After he died, this article was published saying that he had been the literary curator of Hitler’s Museum of the Extinct Race.

DW: That’s the story he told.

BP: That’s the story that was told about him.

DW: Right, but it must’ve come from somewhere.

BP: Well, yeah. This is the thing. The one question that still haunts me after writing the book well after it’s been published is, to what extent was he complicit in telling that story? Anyway, it’s pretty clear that that story isn’t true but I’ve come to believe there is something that is similar that is true that would’ve actually made perfect sense to him at that point when he heard about this museum—that that’s what he was working on.

DW: Right, because we explain stuff to ourselves in order to be able to understand.

BP: Well, to have gone through anything in the Holocaust, must have been in many ways—I don’t mean this in a disrespectful way—the most kind of meaningless experience. It was literally horror for horror’s sake, right? And so, when you’re searching for meaning in that, you’ll end up attaching to something that in any way makes sense to you. And so I think he, without spoiling too much, was in this Talmudkommando, which was a group of scholars who were tasked with sorting through books that had been stolen from congregations around the Reich that had basically been destroyed. He didn’t necessarily know why he was doing it, so this Museum of the Extinct Race would’ve seemed perfectly reasonable to him as the explanation.

DW: Also, it was enabling him to live by having that job because he was not sent to a gas chamber.

BP: Yes, and I think there was a massive guilt complex. When he was taken to Auschwitz, he was actually still reasonably healthy, right? So he spent six odd weeks in Birkenau in the Czech family camp, and people died en masse there from starvation. They weren’t being gassed and shot or what have you in that particular sub-camp.

DW: This was slave labor.

BP: But they were still worked to death and they were still starved and there was horrific disease and whatever, but he had an advantage going in there thanks to this Talmudkommando that he’d been in, because he had better rations. He had decent accommodation for sleeping arrangements, things that his friends and his family didn’t have. His brother went to the Czech family camp and they liquidated that camp every six months, right? And his brother was in the first intake and his brother was gassed after the first six months was up. He blamed himself to his dying day for the death of his mother. He genuinely believed that having taken rations from his mother in this Czech family camp caused her to die because when they did the selections, the mother was chosen to stay behind, which meant be gassed, and he moved on. He believed that had he not taken those rations, she would’ve been healthy enough. She would’ve been at that time in her late fifties, early sixties. They weren’t moving any late fifties, early sixties women into work camps. She was gonna die whatever happened.

So, all these things, his involvement in telling his story would’ve been a way to explain to himself why he survived, and maybe not assuage the guilt, but at least understand the cause of the guilt or make some sort of peace with the guilt and say that he survived through being part of this incredible plan that the Nazis had to make this museum and that was just luck, because really, 90% of survival was luck.

DW: Maybe more.

BP: Yeah, exactly.

DW: I mean, it’s just so hard to imagine. One cannot.

BP: No.

DW: It’s just not possible to realize that humans do this to each other, it’s not a unique happening.

BP: No. I mean, that’s the horrific thing. I always think about, “Never again, never,” and it just happens again and again. Different scales, different situations, Cambodia and Rwanda . . .

DW: Now Yemen.

BP: Yeah, exactly.

DW: Which no one wants to talk about.

BP: It’s horrific. South Sudan, Darfur. It’s unbelievable what humans are capable of . . . And it’s interesting because when you really kind of commit yourself to writing about this and trying to understand it, it gives you perspective on both the best that people can be and the worst. I like to think that you end up with some sort of equilibrium because sometimes you’re like, “Wow, people are amazing and the things they can do to survive and to help each other is just extraordinary,” and then you look at the other side of it and you just go, “Wow, people are terrible.”

DW: Right. But we can contain both of those realities. And it’s painful to realize that what happened to the people in your book, they’re just a few people out of millions.

BP: Someone says, “Are there still Holocaust stories to tell?” Yes, there are so many because every survival story appears to be unique.

DW: Even the ones who didn’t survive . . . Some of the work is about remembering and allowing them to live in memory or in imagination.

BP: It’s very interesting you say that because a thing that happened for me in writing the book, one of the most extraordinary experiences, was I got an email from a 94-year-old guy in London and he said to me, “Look, here’s my class photo from 1942 in Prague. I’ve spent the last 30 years since my retirement trying to find out what happened to all the people in my class. The only person I couldn’t find was my teacher, Jakub Rand, and every year I type his name into Google”—and I just laugh, this 95-year-old guy, typing in Google every day—”Every year, I type it in Google and I try to find him and nothing, and this year it came up. It came up with you,” because people have been talking about this kind of crazy guy who’s running around trying to find his grandfather’s story and he’s on an obsessive quest . . . so he said, “I think this might be your grandfather. I think Jakub Rand, this teacher, might be your grandfather.” Now, this photo I can clearly see is my grandfather. I mean, at 85, he didn’t look greatly dissimilar to what he looked like at 25, right? A somewhat older version.

Anyway, I ended up going and meeting him, I went to London. He lives in Suffolk now, an amazing, amazing guy. He said to me, “I want you to promise me one thing, that when you come to write this book, I’m gonna tell you about all the kids in my class.” I think probably about 90% of them were killed, right? He said, “I want you to write about them as people. Make them characters, right? My quest is to give these children life that was denied them.”

DW: Right.

BP: So there’s chapters in the book that take place in the school where my grandfather was teaching. Actually, some of them reappear in later chapters in Terezin and also in Birkenau. When we came to editing it, my editor was like, “Oh, do we really need all these kids in it?” I agreed with 95% of her edits. I said, “This is one thing I’m gonna dig my heels in ’cause I made a promise to this guy, that these kids are going to become people again.”

That to me was really important. And similarly, my grandfather’s best friend, George Glanzberg . . . This guy, his name’s Frank Bright, Franticek Brichta, as he was back then, said to me, “Did your grandfather ever mention someone called George Glanzberg?” I said, “Funny you should say that because he mentioned him once and for some reason the name has stuck in my head.” He mentioned him during my brother’s bar mitzvah during his speech, and he just mentioned him in one line, which was, “Why me? Why not Glanzberg?” He’s talking about his survival, and I never knew who Glanzberg was but the name always stuck in my head. I was ten at the time of my brother’s bar mitzvah, so it’s strange. He said, “Glanzberg is the guy standing next to your grandfather in the photo. He was the other teacher. It was his best friend.”

DW: And they worked together.

BP: They worked together in Prague, unquestionably. They were absolute best friends. They hung out all the time together. They both had doctorates and were highly learned, but they were both young guys and what have you.

So, it was just amazing to hear about this man who just sounded like a fantastic guy, and I could see where my grandfather would’ve loved him, right? And also why my grandfather felt so guilty about having survived without his best friend when they actually had almost identical trajectories through the Holocaust. The only difference was that my grandfather was not well enough to go on a death march and was left behind in one of the camps, and George died on that death march.

DW: Have you heard from people who have read your book, how it affected them? Have people talked to you about how it connects to their own experiences?

BP: Yeah. I get a lot of people, particularly people with Czech backgrounds who say that they found the stuff about Theresienstadt and also life in occupied Prague particularly powerful for them to understand what their family had experienced, but also we’re talking about my grandmother’s side. My grandfather was working in a kind of hut a couple hundred meters out of Theresienstadt, whereas my grandmother and my great grandmother, that being my grandfather’s mother, were probably one in the laundry, one in the kitchen, what have you.

DW: This is the woman whose mother, if I remember right, was not Jewish, so she was able to stay in Prague and smuggle food to them.

BP: Well, interestingly, this was not meant to be about my grandparents initially. This was a completely single-minded quest to find out my grandfather’s story, which came to nothing very early. But on my way back, I went through Prague and my mum’s cousin was there. He’s a fantastic guy, and we’re having coffee and he said, “Look, I know you’re looking for your grandfather’s story, but I have something you might be interested in.” His mother, who was my grandmother’s youngest sister, had just died. He was cleaning out her house, and at the back of her closet he found a shoebox, and in it were these letters on the most fragile paper, the tiniest handwriting in pencil.

He goes, “These are letters that your grandmother sent from the concentration camps to her mother back in Prague.” In them, there was talk about food and medical supplies and there’s a line that says something to the effect of, “We were just where they use gas. I’ll tell you about it when I get home”—amazing stuff from within the actual Holocaust experience. They permitted little postcards to come out, but these were full letters, so these were smuggled out, right? They also talked about a Mr. B, who was the conduit for getting the supplies in and out.

Yeah, so my grandmother and my great grandmother were in contact through almost all of my grandmother’s time in the concentration camps. The only time they weren’t was during her reasonably short stay in Birkenau, because there was a story that one of the letters was intercepted, and this happens in the book. It was intercepted by the Nazis and they called her out during one of the parades and they called a girl out to translate. The girl was apparently a 15-year-old Polish girl. They actually just asked for a volunteer. They said, “Can someone translate this letter?” This girl comes out and she holds the letter and she reads it, in inverted commas, and literally makes up what’s in the letter so that it’s completely innocuous. My grandmother was beaten to within an inch of her life, but she wasn’t sent off and killed. And my grandmother spent a long time afterwards trying to find that girl because she owed her her life, and she didn’t even know the girl either. That’s the amazing part—this was a girl who just took it upon herself to essentially save my grandmother’s life.

Anyway, my great grandmother as you said wasn’t Jewish, or she was a convert, but by Nazi standards she wasn’t Jewish. So, she and the two youngest daughters—my grandmother was the oldest of four girls—stayed in Prague, and my great grandfather, who was Jewish and the two elder sisters, my grandmother and my auntie Irene, went to concentration camps, and yeah, they stayed in touch throughout. My great grandfather died, was killed. My grandmother and her sister survived. It was thanks to really the extraordinary bravery of my great grandmother.

So I set off to find my grandfather’s story, but I ended up being in absolute awe of my great grandmother, whom I knew. I was thirteen when she died, and she was in her late eighties. You know what late eighties looks to a little kid: She was impossibly old and shriveled and what have you. To think of her and the stories I heard about her whilst researching this, and what I found out through various family members and friends, was just amazing. She visited my grandmother in the concentration camp, in Theresienstadt. I thought that was just impossible. When my cousin, my Czech cousin Ludwig, told me that they had visited, I was like, “That’s not possible.” Not only that, my editor called me on that and said, “There’s no way that happened.” She goes, “Unless you find evidence of people actually being able to visit concentration camps, that can’t be in the book.” I spent a long time, and I found records.

So this story, which seemed completely impossible or at the very least highly implausible, turned out to be entirely possible, because Ludwig had actually spoken a lot to my great grandmother, she was Ludwig’s grandmother and he was very close with her, and in her older days, they spent a lot of time together talking about life and the war and what have you, and she told him a lot of these things.

DW: Wow. So do you mind reading a little bit? It would be nice for people to hear a little, because I think the writing in this book is really great.

BP: Thank you. So this happens when my grandfather is sorting the books in Theresienstadt. He’s met my grandmother, and this was actually a big part of the book because I wanted to find out how my grandparents met each other. And so he’s met her, because she is bunking in the dormitories with my grandfather’s mother, and he doesn’t want to admit it, but he has a crush on her. She is in love with someone else, but anyway. Okay:

She danced between the lines in the kingdom of paper. It started with the slightest glimpse, a blonde curl behind a slanting lamed, a flash of skin, perhaps a wrist, a shoulder, or even a thigh through the crook of a beit. By some mistake of gravity, he had ascended to the heavens where only gods and angels dwelled. He looked at Georg, at Muneles, at Gottshall, at Seeligman, but they were lost between pillars of pulp, blinded to this shimmering sprite. She grew more brazen with the days, revealing more of herself on each new page. There was nothing suggestive in her moves, just the sheer delight of freedom. She cared little for his startled gaze. At times she swirled the ink around her in a frantic pirouette until the words blurred like a shroud across her shoulders.

Jakub sat back and wiped his brow. No, it was pointless. It was like leering at a sister, a child. And was he not just seeing her with his mother’s eyes? He knew how Gusta looked on when they talked, imagining what might have been, what still could be, but theirs was nothing more than a convenient alliance: her packages, his privileges, pooled to create a semblance of plenty. Outside the barracks, away from these books, she danced for others. He had seen her in the park on his way back from the bastion, huddled close to a young man under a tree. And what to make of the other times when she would loiter near the gate at day’s end and run the moment she caught sight of Jakub coming up Südstrasse. Jakub was certain he saw the gendarme right himself before hurrying over to unfasten the lock.

Jakub looked at the SS man by the door. He rarely moved, as if asleep. Only once had he stood to attention, when Eichmann himself came to visit, to compliment these shackled scholars, to show that he, too, could speak in their tongue. It is very important work you’re doing, gentlemen, Eichmann had said. That was before September, before the Council announced the resumption of transports. Before they took Shmuel away. He should have known. Eichmann’s presence boded ill for them all.

DW: I really want to thank you for doing this, Bram. It’s been great.

BP: Oh, thank you.

Click here to purchase this book

at your local independent bookstore

Paige Ackerson-Kiely

Paige Ackerson-Kiely