Interviewed by Allan Vorda

Interviewed by Allan Vorda

Born in Maryland, Neal Stephenson is the son of a professor of electrical engineering and the grandson of a physics professor. The family moved to Illinois and later to Ames, Iowa, where Neal graduated from high school. He received a B.A. in 1981 from Boston University with a major in geography and a minor in physics. Stephenson first made his splash in the literary scene with the publication of the cyberpunk SF novel Snow Crash in 1992. Since then he has published a number of books, usually of substantial length, in the areas of speculative and historical fiction; these include The Diamond Age, Cryptonomicon, The Baroque Cycle (Quicksilver, The Confusion, and The System of the World), Anathem, Reamde, and Seveneves. Stephenson has won numerous awards including the Hugo, Locus SF Award (five times), the Clarke Award, and the Prometheus Award (twice). He lives in Seattle, Washington. His most recent novel is Fall: or, Dodge in Hell (William Morrow, $35).

This interview was conducted on June 18th, 2019, in the lobby of a downtown Houston hotel, before his reading that evening at Christ Church Cathedral.

Allan Vorda: In Fall, Dodge Forthrast becomes brain dead after surgery, whereupon he is placed in a cryonic state until future technology can restore his consciousness. What was the genesis for writing such a novel?

Neal Stephenson: The idea of uploading the brain is something people in the tech world have been talking about for a while, and of course, people have always thought about what happens after we die. Is there an afterlife? Is there something more? Since it’s a topic of universal interest, it seemed like a good premise for a novel. I have also been interested in Milton’s Paradise Lost lately, and I’ve been looking for a way to do something with it. I came at it from various angles over time, and finally decided Fall was a good way to approach it.

AV: This also raises the mind-body problem. As you write, “The mind couldn’t be separated from the body. The whole nervous system, all the way down to the toes, had to be studied and understood as a whole—and you couldn’t even stop there, since the functions of that system were modulated by chemicals produced in places like the gut and transmitted through the blood. The bacteria living in your tummy—which weren’t even part of you, being completely distinct biological organisms—were effectively part of your brain.” Do you agree the mind is dependent on the body? If so, would you qualify whether your consciousness is you?

NS: There is a kind of naïve idea about this distinction between the mind and the body that hasn’t been taken seriously by people who think about it a lot. The idea is that you could just take the brain out of the skull, then keep it alive somehow, yet still have the same person. Everything you’ve just read in that passage is not based on my own ideas, but ideas that have been explored by philosophers, neurologists, psychologists, and so on.

From my point of view as a storyteller, I’m looking for ways to relate an interesting yarn. In the beginning of the novel, when the characters are beginning to scan the brains and put them up as digital simulations on the Internet, they are coming at it from that naïve point of view in which the brain is the only thing that matters. That has some unintended consequences as the situation develops, which eventually get rectified as people come up with a more sophisticated and nuanced view of what it means to be human. The questions you’re raising are explicitly discussed by characters in the book, which they’re working out among themselves as the situation develops.

From my point of view as a storyteller, I’m looking for ways to relate an interesting yarn. In the beginning of the novel, when the characters are beginning to scan the brains and put them up as digital simulations on the Internet, they are coming at it from that naïve point of view in which the brain is the only thing that matters. That has some unintended consequences as the situation develops, which eventually get rectified as people come up with a more sophisticated and nuanced view of what it means to be human. The questions you’re raising are explicitly discussed by characters in the book, which they’re working out among themselves as the situation develops.

AV: From a religious standpoint, various philosophers argue the soul can be separated from the body. The metaphysical existence of a soul is debatable, but throughout Fall you refer to the consciousnesses in cyberspace as “souls.” Why did you choose that term?

NS: Because it’s short—it only has four letters and it’s a term that people would use. I’m trying to depict realistic characters, and I’m trying to use terminology they would adopt, even if it is not the terminology I would use. It’s my job to think about what fictional characters would do and say, and not just what I would do and say.

The word “soul” has all kinds of religious significance, but it’s also used in other kinds of settings. When people talk about an airplane that has crashed or a ship that has gone down, for example, they’ll frequently say, “It was lost with 152 souls on board.”

I wouldn’t read too much into my use of the term. When the characters use it, what they’re getting at is a rebooted consciousness: this digital simulation which has the complexity of the brain on which it was based. It has some of the personality and memories, and it acts and behaves as if it had the full complexity of a living human. When we talk about a human being, it implies a physical body. When we talk about a soul, it seems to be a more precise term for what we’re denoting.

AV: At one point in Fall, El Shepherd wants to destroy the less developed souls who are wasting his money to keep the Process going. El states these “new ‘fruit fly’ processes have to be terminated.” Corvallis Kawasaki counters by saying these souls “are based on human connectomes.” Can you comment on this moral question of what constitutes life, and who has the right to decide who lives or dies? Not insignificantly, this is being debated right now in our country regarding abortion.

NS: The fruit fly reference is to new animals that are being booted up by Spring; she feels the Bitworld isn’t complete until it has birds and bees and other lesser creatures in addition to humans. Spring is trying to create those animals to more fully realize the world in which they’re living. I think both El and Corvallis agree that souls, based on a human connectome, should not be terminated. What they’re arguing about is this new phenomenon of less complicated creatures that have emerged due to the creative efforts of Spring within the story.

AV:“The mass of people are so stupid, so gullible, because they want to be misled. There’s no way to make them not want it.” A lot of fake news is disseminated by the Internet, or what you refer to in Fall as the Miasma. Do you see any solution to preventing all of the disinformation we see? How do we preserve free speech?

NS: I’m not too worried about free speech. The constitutional guarantee of free speech refers to governmental activities, and basically says the government doesn’t have the power to restrict people’s exercise of free speech. It doesn’t say anything about private companies and their activities. Platforms like Facebook, YouTube, and Twitter have been gamed by hostile state actors who are actively using them as part of a disinformation campaign, and to engage in a kind of non-shooting war with the United States. That is all completely obvious and out in the open at this point, and by failing to prevent this from happening, social media platforms are failing in their responsibility as corporate citizens. It appears they’re trying to clean up their act and get better at this, but I don’t think they’re doing it fast enough. I question whether or not they have the ability to ever completely succeed at it, given their whole corporate valuation and revenue model is based on running these systems algorithmically, without any humans in the room.

I can’t remember who is quoted in that line and I’m not sure it matters, but to answer the question on disinformation: I don’t see a solution. I think it’s a terrible problem, and we’re in a terrible situation because of it. It will be very challenging for the responsible companies to change their ways. The only way I can see forward is for people to get more skeptical about what they see, which is difficult, because a lot of people are happy to swallow inaccurate information that aligns with what they feel. Along with skepticism, part of the solution might be that these platforms will fade away over time and be replaced by new ones. Maybe in ten years, we will be using different platforms that have been invented in the wake of the situation of today.

AV: This is a peripheral question, but nowadays a writer can Google a topic and get information immediately, whereas before the Internet writers had to scour journals and microfiche in the library to find what they needed. It was almost like being a detective—time-consuming, yet often fun and rewarding. Have we lost something if writers no longer have to spend time in the library, or does it not really matter?

NS: I think it does matter, because serendipity is a valuable side effect of using old school libraries. When you’re walking down a shelf of books, looking for one particular volume you think is relevant, you may see other books surrounding it that are useful in ways you didn’t expect. You can get the same results when flipping through an old paper card catalog or microfiche. One of the things digital information storage systems have not done well is reproducing that kind of serendipitous discovery. Balanced against that is the fact it’s much easier to find things on the Internet; you don’t have to physically go to the library to do research, so everything just goes much faster.

I try to develop skills in how I use the Internet to help make up for that a little bit. Rather than doing one search on one set of search terms, I’ll try to create some serendipity on my own by trying a bunch of related search terms, and then searching outward from the first hit to make sure I’m not missing anything.

AV: The Forthrast homestead is located in northwest Iowa, a borderless, undefined territory called Ameristan that is populated by uneducated, gun-hoarding cults; one group in Iowa is building a two hundred-foot tall flaming cross, and another in Nebraska actually crucifies people. Yet you also suggest that Jake Forthrast, a survivalist from Idaho, can actually change into a reasonable human being, and your depiction of city-dwellers isn’t without criticism. What is your opinion on how people in rural areas differ in thinking from people in cities?

NS: The situation that exists, not only in rural areas but all over the country, is that there is a divide. We tend to refer to it as red state versus blue state, but it’s not really correct to think of it in terms of states—it’s more finely detailed than that, the boundary is a very complicated fractal that can exist even between neighborhoods.

In the case of the novel, this is the same situation. Some areas are strictly blue-state; for example, in the town of northwest Iowa, there are dentists and doctors and all the people have learned to live in the modern world productively; they have money and education and they know how to do things. On the other side, past this invisible boundary, there are the have-nots who are suffering because they’ve fallen under the grip of algorithmically-generated memes that are coming into their eyes and ears all the time, making it impossible to make sense of what is objectively real. This is an exaggeration of the situation which exists today. The purpose of the book is to provide a kind of glimpse into the future, a cautionary tale to make people consider the consequences if we keep going down this road. I try to depict some characters, such as Jake, who are trying to make connections, to address these difficult situations and find ways to work with it.

AV: Your book Cryptonomicon might be the only work of fiction to mention the Reimann zeta function, and Fall also invokes some mathematical statements such as “the plot of the integral.” The majority of your readers probably don’t know the meaning of mathematical or technical terms. In what way does this add to your writing?

NS: Based on my interactions with readers at my readings, I think this may be a pessimistic view. I’ll allow a fair number of people won’t necessarily understand these terms with absolute precision, but that's not what I’m thinking about when I’m writing this stuff. I’m in the business of writing stories about fictional characters, some of whom are well-versed in technology, mathematics, engineering, computers, etc. My strategy is to show them doing and saying things people like this actually do and say. Some readers may not totally understand some of the jargon, but that’s how real life is. I’m hoping the result is to make the book seem more like real life, and in that way help the reader suspend their disbelief, and find the whole thing realistic and plausible.

AV: In Fall, Time Slip Ratio refers to the differences between Meatspace (real world) and Bitworld (cyberspace) time. Enoch Root is a recurring character in your novels who is essentially immortal and never seems to age. If we consider the hypothesis that all reality is a computer simulation, then can Meatspace in the novel also be a simulation, and is Enoch Root from a reality outside this simulation? This could provide an explanation of Enoch Root’s ostensible immortality due to Time Slip Ratio.

NS: What you just described is something I’m hinting at in the book, so I would say that you correctly pieced it together in a way that makes sense. I’m reluctant to say, “Yes, that’s it,” because the heart of this is not to just baldly describe the state of things. It is a natural question that arises: If you posit we can simulate reality with our computers, then the next question you have to ask is, could our world be a simulation on someone else’s computer. Then it turtles all the way down.

AV: If given the option to upload your consciousness, would you do it?

NS: I’m quite skeptical of this kind of thing myself. I would have to know a lot more about the process and how it’s supposed to work before making such a decision. This book isn’t so much me advocating that process as just saying, “Let’s suppose this would work to some degree and use that as a basis for a yarn.” I want to tell a story and see where the story takes us.

AV: Do you play video games? If so, which ones and does this add or detract from your writing?

NS: I used to play them more in the past. I like solo games, and the trend in the last decade has been towards multiplayer games. This is driven by economic considerations: game publishers get more bang for their buck if they can get customers to entertain each other. I would rather be on my own. My time spent playing video games has gone down, but I’ve played a little bit of Red Dead Redemption 2, and a little bit of Anthem recently. I’m probably more apt to play board games than video games at this point.

AV: Fall incorporates straight fiction, science fiction, and fantasy. Was it difficult to plot out three distinct genres?

NS: I don’t see genre that much while I’m writing. Those are distinctions that are drawn by people outside who want to classify books. There is nothing wrong with those distinctions—by assigning genre labels to different books, we make it easier for readers to find books they’re going to like, to find each other, and to form communities. So I have nothing against it, but those distinctions are all invisible when I’m actually doing the work. I don’t have any mental sense of shifting gears; it’s all an organic whole to me, and so there are no hurdles or difficulties associated with moving from one to the other.

AV: As a writer, you received a lot of recognition for writing science fiction, but do you feel that you’ve been stereotyped as an SF writer? Do you think this prevents critics from considering you for awards such as the National Book Award or the Pulitzer Prize?

NS: Probably to some degree, although I’m not particularly worried about it. There is an odd mentality around genres versus so-called literary fiction that I’ve been observing for some time, although more as a kind of anthropologist than a participant. I wrote about this a long time ago in a Slashdot interview, explaining what I call Beowulf versus Dante writers: Beowulf and The Divine Comedy are both great works of literature, but The Divine Comedy was written by a person who had a patron, whereas Beowulf probably just bubbled up from some guy telling stories in a bar. The same situation occurs today; you have some people working in a more literary area, where typically they’re not supporting themselves through writing—they’re employed by a university or something that effectively acts as their patron while they work on their art. Then you have writers who are making their living at it, and they sell a whole lot more books. Occasionally, you have someone who can do both, which is a marvelous thing.

I’m completely uninterested in drawing value judgments between those two styles. Consequently, I’m not a big fan of people who live in one camp and look down their nose at people in the other. It’s quite possible I’m in a weird place and I’m not going to be winning a lot of awards, but I really don’t care. I’ve been amazingly fortunate in my career. There are a lot of writers who make more money than I do, and a lot of writers who make less. My position has given me the ability to write full time and have a good standard of living, so I consider myself lucky. Whether I win awards or literary acclaim means nothing to me.

Raymond Antrobus

Raymond Antrobus

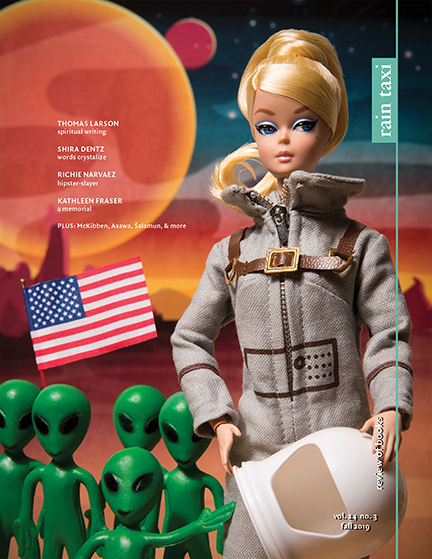

To put it simply: I’m a Minneapolis photographer with a mild obsession with Barbie. Influenced by imagery from the ’50s and ’60s, I create scenes with the dolls in studio that have a sense of whimsy mixed with a little sarcasm. To me, Barbie is a positive, strong and empowering figure and I try to utilize her to create conversation. And to answer your question, I only have around 40 dolls.

To put it simply: I’m a Minneapolis photographer with a mild obsession with Barbie. Influenced by imagery from the ’50s and ’60s, I create scenes with the dolls in studio that have a sense of whimsy mixed with a little sarcasm. To me, Barbie is a positive, strong and empowering figure and I try to utilize her to create conversation. And to answer your question, I only have around 40 dolls.