By Scott F. Parker

Here . . . is how I give you me.

Here, also, is how I give you you.

Here, finally is how you give me me.

—David Shields, Enough About You

It’s about other people’s memoirs.

Why they write them, what they mean.

It’s very complicated. I don’t entirely understand it.

—David Shields, Heroes

I find myself inclined at the outset to consider the locution with which I begin here: I find myself. I find myself, as I always find myself, anew. Yet my consciousness resists this finding, preferring instead to play catchup with the moment just passed—or, when things are going well, narrowing in on the moment just arrived—and organizing this into the narrative not of a new self or self in new circumstances but of the same old compadre I’ve been living with as long as I can remember: the rote company I keep as I go about my days.

This is an experiential report, not a philosophical one. The deepest plot is uncovering the process by which the self comes into being. Seen from any meaningful remove, the self is inextricably original at all times. But such a remove is just the missing ingredient as I look up from the same computer screen to look out the same window through the same eyes as I think the same old thoughts I’ve thought a hundred times before. If I don’t get bored with this story it’s because I’ve got so much invested in the drama of it.

Rarely, when I engage with plot-driven books, can I bother to keep the characters straight or follow the storyline. Sometimes I start looking around for the good bits, the inner monologue, the narration, the consciousness tucked away in the work. But usually I turn my attention to books that can hold it. I almost never care what happened, but I almost always care what it means to whomever it meant something.

Experience filtered through consciousness to produce meaning—I gather these meanings and shake them around in my own consciousness, letting them fall where they may. I have always been a synthetic thinker by disposition, trusting that when I shake things just right they will settle to reveal unified reality. This method inclines me toward agreement. My ears are attuned to the songs I can harmonize with. I don’t nitpick the details, I borrow support for the structure and move on looking for other supports.

This makes me a bit of a cypher, adopting the ideas and characteristics of those around me, trusting that all is fuel for the fire. But I haven’t set myself up here merely to knock myself down. I want to land on my feet, albeit on new ground. As a philosopher becomes an artist, the fuel still burns, but it is enough now to keep the fire going through the night and trust that the embers will burst into flames again when someone comes along to blow a little life into them.

I read now ever on the lookout for what will be useful to me. I pause briefly in admiration when I find it, then set about figuring the best way to smuggle it off for my own ends. Everything I read becomes mine. To say that these essays are, because born of conversations and mutually created, collaborations, isn’t quite fair. Shaped by me, my interlocutors can’t but become who I want them to be. The “I”s of my collaborators are foils, negatives, constructs of my vision.

The following David Shields, for example, is as much mine as his own. Thus spake subjectivity.

Shields is one writer who gave me permission to read this way. Enough About You was one of the first books I’d ever read in which I recognized the self in which I lived. Of course, as soon as I had the permission I no longer needed it, and never had. So I asked him if he would like to join me in the ancient practice of two white guys bullshitting and consciously inspire a character based on himself in my imagination.

Shields is one writer who gave me permission to read this way. Enough About You was one of the first books I’d ever read in which I recognized the self in which I lived. Of course, as soon as I had the permission I no longer needed it, and never had. So I asked him if he would like to join me in the ancient practice of two white guys bullshitting and consciously inspire a character based on himself in my imagination.

He was teaching at a writing conference at Reed College. We met on campus and set about for a walk and talk through Southeast Portland one summer twilight, the day’s heat dissipating, shadows beginning to elongate, outlines beginning to blur. Though the dialogue survives, the identities of the speakers have not been preserved. The point wasn’t authorship, the point was the conversation. And the conversation—all of it—was in the air.

I suddenly flashed on this unbelievable course that I took as a graduate student that to me was the absolute parting of the Red Sea. It changed my whole writing life. The course paired a novel and a work of autobiography that did the same work. So, Great Expectations and Rousseau's Confessions; Nabokov’s Speak, Memory and The Real Life of Sebastian Knight. The point of the course wasn’t to prove how superior the essayistic gesture was to fiction, but that’s what I got out of it. I felt like in the essayistic work the writer was actually doing some intellectual lifting. I was bored, as I still am, with the notion that a writer is supposed to be this carnival barker storyteller, filling in tiny bits of intellectual glitter here and there. In the works of essayistic meditation that’s the whole thing. It’s a much more exciting readerly and writerly experience.

I suddenly flashed on this unbelievable course that I took as a graduate student that to me was the absolute parting of the Red Sea. It changed my whole writing life. The course paired a novel and a work of autobiography that did the same work. So, Great Expectations and Rousseau's Confessions; Nabokov’s Speak, Memory and The Real Life of Sebastian Knight. The point of the course wasn’t to prove how superior the essayistic gesture was to fiction, but that’s what I got out of it. I felt like in the essayistic work the writer was actually doing some intellectual lifting. I was bored, as I still am, with the notion that a writer is supposed to be this carnival barker storyteller, filling in tiny bits of intellectual glitter here and there. In the works of essayistic meditation that’s the whole thing. It’s a much more exciting readerly and writerly experience.

You have to acknowledge the ways in which the culture pushes one. The essay has been experiencing an ascendency the past two decades or so. A writer has to find his way to his real interests. That journey is always an interesting one. Whatever you do only as homework, as it were, learning the craft of how to be a writer, eventually you have to say goodbye to all that.

Exchanges like these are part of being loyal to the work and continuing the conversation. I’m also interested in friction, in traction. And one never knows where things can lead. Basically, I like thinking. And if someone can help me think about work and art and form, I’m all for it. We’re taking a pleasant walk and talking. Dialogue leads us on to new insights, new understandings.

The limits of self are pretty obvious in the sense that if the work is only saying here is my life, I was abused by my step-father, I’m an alcoholic or addict or pedophile or whatever, it’s just simply trapped in the carapace of the self. Every art form has its inherent strengths and limits. For instance, film at its best is this incredibly visceral medium, but at its worst is this kind of insane sensation of clown-show pyrotechnics. There’s nothing there. The novel at its worst is a storytelling machine that doesn’t have any purpose other than to keep the reader turning pages. The memoir or book-length essay at its worst is just the religion of the self. It has to come down to Montaigne’s line, “Every man has within himself the entire human condition.”

The key is to find in yourself glimmers of some—I don’t know if you’re supposed to say this anymore—universal predicament. I use myself as a lightning rod to get at deeper subjects. The key is to rotate the self toward metaphor and meaning. If the work stays duty-bound toward the hard-wired self it’s likely to be a truly boring work. If the work uses the self as a launching pad to get into interesting aspects of human nature, that shows its value.

What personal essayists do: keep looking at their own lives from different angles, keep trying to find new metaphors for the self and the self’s soul mate. The only serious journey, to me, is deeper into self until you reach the place where the self is writ large as another self.

One of the things we can do when we’re fed up with the culture is look around to see how others are trying to respond—and memoir, at its best, can help with that.

What distinguishes our lives are not what happens in them. That might be a slightly privileged perspective of someone in a middle-class, capitalist, Western democracy, but for the majority of readers we’re talking about, the incidents are relatively the same. We’re born, we live, we love, and we die. And the endless rehashing of those different experiences is not truly distinctive. What is distinctive is the quality of your intelligence and the way you relate to that story.

Thinking of Wallace and the book at its best as the bridge across the abyss of human loneliness, what happens in a lot of novels and memoirs is the writer tells himself he’s constructing that bridge, but all he’s doing is relating anecdote after anecdote, scene after scene. “The ax that breaks the frozen sea within us” is actually exquisitely rendered and pitiless consciousness. It’s not twenty pages about something that happened. The work that actually brings human loneliness to some kind of temporary halt is work that delves down very deeply into consciousness and doesn’t beat around the bush with scene and incident the way the novel and memoir tend to.

To essay is both to render consciousness and to create it.

Somebody who is writing metaphors of self or stories of self is simultaneously writing the self. Everything that you write, including criticism and fiction, writes you as you write it.

This guy walking by, his T-shirt says, “Hustle, hit, never quit.” There’s a kind of narrative he’s telling himself about football or being tough. In those four words he’s telling himself a really important story. What distinguishes human animals from muskrats or whatever is we do have written, spoken language. It is the defining aspect of human beings and the preeminent artistic medium. We are aware of our own mortality, and we’re specifically aware because we have language.

This guy walking by, his T-shirt says, “Hustle, hit, never quit.” There’s a kind of narrative he’s telling himself about football or being tough. In those four words he’s telling himself a really important story. What distinguishes human animals from muskrats or whatever is we do have written, spoken language. It is the defining aspect of human beings and the preeminent artistic medium. We are aware of our own mortality, and we’re specifically aware because we have language.

Another line of Montaigne’s: “I have no more made my book than my book has made me.” There is something that happens when you complete an act of communication from writer to reader. There’s a weird way in which the author becomes the narrator the reader perceives. If I take a stance in the text that is not one I ever really felt outside the text, to some degree I adopt that attitude in real life. Having pretended to be this exaggerated version of myself, I discover through the reader’s eyes that I am him.

The self is perpetually being constructed and deconstructed.

I repeat myself because I only have a limited number of rhetorical moves.

The whole idea is that you use nonfiction as a framing device for questions like “What is the self? What’s real? What’s true? What’s knowledge? What’s memory? How much can one self know about another self?” It’s a funhouse mirror for really difficult and quite serious ontological questions having to do with knowledge and primacy and truth and memory.

What is the self?

“Okay, hi, I’m Joe Blow and I’m going to write a six-hundred-page memoir.” I’m not interested in any continuous and stable self. I’m interested in the self as a malleable form. The best work splinters the self instead of treating it like some eighteenth-century cathedral.

“Okay, hi, I’m Joe Blow and I’m going to write a six-hundred-page memoir.” I’m not interested in any continuous and stable self. I’m interested in the self as a malleable form. The best work splinters the self instead of treating it like some eighteenth-century cathedral.

This question remains: can Humpty Dumpty be put back together again, in some slightly new way?

What is the self?

The first thing that comes to mind is “a fiction.” Let’s explode that fiction.

Here’s a metaphor. It’s not a metaphor of the self but a metaphor of how the self seems to operate. The best work of this kind, there’s this quality in the work of just barely (at the beginning of the work) you see this ship edging out from beneath some vague clouds. And you kind of feel like “I’m not really seeing that, it’s just a bunch of jottings.” You know Maggie Nelson’s Bluets, it’s just about the color blue. Then you see the ship keeps moving into view. You keep on getting this glimmer of this ship that’s breaking into view, but you think no it’s just the clouds or just the rocks or just the shimmer. Then slowly but surely that ship goes from being a ghost ship that you thought maybe was there to, Christ!, the author really knew what she was doing. It is there! So at the end of Bluets you realize this book is not about the color blue; it’s not about her friend who got paralyzed; it’s not about her ex-boyfriend. It’s very much a book about, How we do we live with mortal knowledge of all kinds? The death of a relationship the death of a limb. How do we reconcile ourselves to loss of all kinds, especially the ultimate loss of our own selves?

What is the self?

There are more ways than one to write about the self. The relationship between the self and its environment—its context—works both ways. The “subject” of an essay is relational to its subjectivity. The magnet gets magnetized.

If you went right to the core of it—the great thing is when the world pops open so that you can see that that kid walking down the street wearing the “never quit” T-shirt is part of one metaphorical constellation with this essay.

Ross McElwee’s Bright Leaves looks like it’s about a guy’s tobacco farm, but really it’s a kind of metaphysical contemplation on how we’ll do anything—light up a cigarette, build a birdhouse, marry the wrong woman, sing in a church choir when we don’t believe in god—to get a brief feeling of transcendence. What is so great about it is that by going into all these different pockets, he connects very disparate parts of the world for you. It makes for more generous art, and it makes for a deeper penetration into existence, and it makes for a much more deeply layered work than if you just . . . There’s this line of Duchamp’s, “Consequently, in the chain of reactions accompanying the creative act, a link is missing. This gap, representing the inability of the artist to express fully his intention, this difference between what he intended to realize and did realize, is the personal 'art coefficient' contained in the work.”

A lot of this is back formed. Something happens, then you back form all these explanations. It’s a kind of retrospective fallacy, that you knew what you were doing. But the narrative is often imposed after the fact.

I guess I have philosophical and strategic reasons for collaboration. Part of it is it’s fun talking with someone, it’s interesting, it gets you out of your own head. At some point you do start to run out of ideas, and it’s good to have new people challenge you. I’m fed by new writers, new material, new collaborators, just on a very humble level of being intrigued by new stuff.

Like many writers, I’m sort of building one big argument. All of my work is one long book. And this structure gains strength by bringing other people, other ideas into its orbit. I argue with myself all the time, that’s what the essay does. Sometimes it’s more rhetorically effective if your interlocutor is outside yourself. It gives me more points of contact with the culture, more opportunity to push my art and nonfiction forward in a particular direction. I’m trying to amass an argument that’s unassailable in my own vainglory. In my imagination.

What is the self?

You can see the purpose of life this way: to be the material for art. There are some experiences, if they aren’t going to be a book, a film, what are they good for? There’s something about recording. Spalding Gray says, “the camera eroticizes space.” The prospect of publication galvanizes my attention. Without it, would I bother with these thoughts, or would I simply enjoy our walk together? Some of this is just a relatively standard poststructuralist gesture to the ways in which language doesn’t just register meaning but also creates it. But the art makes the life come alive. It can.

The legend goes that to counter Berkeley’s idealism, Samuel Johnson kicked a rock and said, “I refute it thus.” I don’t want to say that if a tree falls in a forest and no one’s there to write a book about it the tree didn’t really fall. What about something softer, like the author’s presence affects the tree? I think to pretend otherwise and maintain some nineteenth-century version of objectivity is the realm of fake scholarship, fake memoir, and fake journalism. For better or worse, I’m very interested in foregrounding that pretty damn high.

So as not to exaggerate the position: real people die real deaths and real people give real births and real people fall in love. My language covering or not covering it has zero to do with the quiddity of what that.

When Wittgenstein says, “Whereof one cannot speak, thereof one must be silent,” and when Lao Tzu says, “The Tao that can be named is not the eternal Tao,” they’re saying so in language. The things that cannot be said can only not be said in language.

One wants to go anywhere but deeper into solipsism. The world is real. But as an artist I’m very suspicious of any verbal art that tries to be or pretends to be transparent. It’s so naive in trying to seduce the reader into believing things are simpler than they are that it becomes fascistic. It’s escapism. It doesn’t bear even the remotest relationship to how people actually talk and write and think and behave. I want work that through its language and syntax and structure and metaphors captures what it feels like to be alive as a human being.

It feels like this: a clear dark night beneath the fir trees of Reed’s campus. I can’t see anyone else, and barely myself. I connect through conversation as through writing and reading as through self-inquiry. But the thing about connections is they’re only connections because eventually they break. I am anonymous in the end even to myself.

Today Rain Taxi celebrates Boards. Nonprofits like Rain Taxi—and they are legion in the literary publishing field—are essentially run by people who volunteer their time, insights, and expertise to forward the particular mission of their organization. These individuals perform the juggling act of both attending to an org’s present-day needs and imagining a more vibrant future—no small feat! Over our 25 years we’ve been blessed to have some extraordinary folks on our Board roster who have pulled this off, and that remains true today. In various configurations, our Board members have been working harder than ever to make sure that Rain Taxi can continue to serve the literary community despite the formidable challenges posed by the pandemic. We hear a similar story from many of our kindred nonprofits at this time, and we are heartened by it—the world to come will need all the forces for good it can muster. So three cheers to the good folks who keep organizations like ours on track; though you work largely behind the scenes, we see you, and we salute you!

Today Rain Taxi celebrates Boards. Nonprofits like Rain Taxi—and they are legion in the literary publishing field—are essentially run by people who volunteer their time, insights, and expertise to forward the particular mission of their organization. These individuals perform the juggling act of both attending to an org’s present-day needs and imagining a more vibrant future—no small feat! Over our 25 years we’ve been blessed to have some extraordinary folks on our Board roster who have pulled this off, and that remains true today. In various configurations, our Board members have been working harder than ever to make sure that Rain Taxi can continue to serve the literary community despite the formidable challenges posed by the pandemic. We hear a similar story from many of our kindred nonprofits at this time, and we are heartened by it—the world to come will need all the forces for good it can muster. So three cheers to the good folks who keep organizations like ours on track; though you work largely behind the scenes, we see you, and we salute you! Today Rain Taxi celebrates the

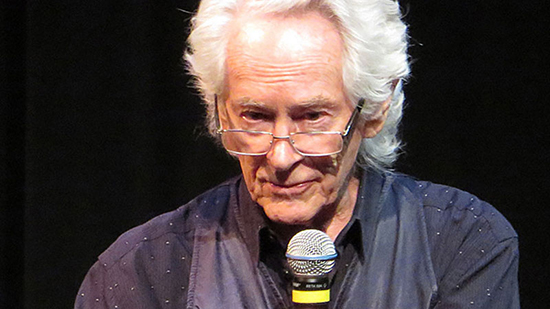

Today Rain Taxi celebrates the  legendary Beat writer Michael McClure, who died on May 4 of this year at the age of 87. We at Rain Taxi had reviewed his books and CDs (check out

legendary Beat writer Michael McClure, who died on May 4 of this year at the age of 87. We at Rain Taxi had reviewed his books and CDs (check out  Today Rain Taxi Celebrates Alec Soth, photographer extraordinaire, whose debut book Sleeping by the Mississippi we reviewed back in 2004. A riveting work of reverie (and including a smart text by Patricia Hampl), it shows exactly why photo books are such an important part of what we think of as the literary landscape, and why we at Rain Taxi keep a happy eye on the medium. A book aficionado to be sure, Soth put another intriguing angle on his vision of photography when he began issuing publications that split the difference between zines and artists books, many under the moniker of a “pretend business” publisher called Little Brown Mushroom. We subsequently caught up with Soth via a review/studio visit on the occasion of a 2010 major retrospective of his work (

Today Rain Taxi Celebrates Alec Soth, photographer extraordinaire, whose debut book Sleeping by the Mississippi we reviewed back in 2004. A riveting work of reverie (and including a smart text by Patricia Hampl), it shows exactly why photo books are such an important part of what we think of as the literary landscape, and why we at Rain Taxi keep a happy eye on the medium. A book aficionado to be sure, Soth put another intriguing angle on his vision of photography when he began issuing publications that split the difference between zines and artists books, many under the moniker of a “pretend business” publisher called Little Brown Mushroom. We subsequently caught up with Soth via a review/studio visit on the occasion of a 2010 major retrospective of his work (

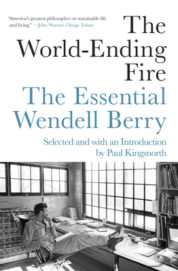

Happy Earth Day, readers! Today Rain Taxi celebrates writing about climate change. Climate justice is a cause we believe in whole-heartedly and we’ve been privileged to cover it on almost every front. This writing, increasingly important as humanity grapples with how we can best take care of the only planet we have, comes in all forms. We’ve reviewed books of nonfiction such as

Happy Earth Day, readers! Today Rain Taxi celebrates writing about climate change. Climate justice is a cause we believe in whole-heartedly and we’ve been privileged to cover it on almost every front. This writing, increasingly important as humanity grapples with how we can best take care of the only planet we have, comes in all forms. We’ve reviewed books of nonfiction such as

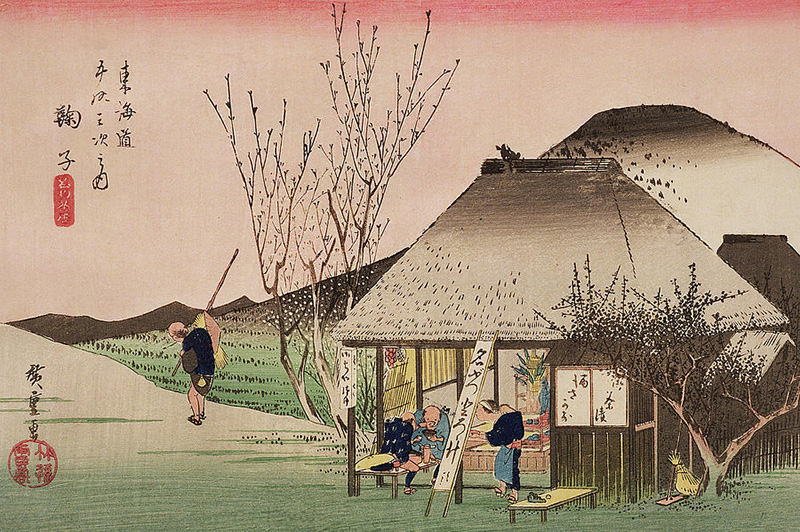

Teaism was Taoism in disguise.

Teaism was Taoism in disguise.