photo by Kristen Houser

Interviewed by Ashley Inguanta

Chris Wiewiora knows how to begin and begin again. He was born in Buckhannon, West Virginia, and then as a child he started a new life in Warsaw, Poland, with his parents, who were undercover Evangelical missionaries there. Wiewiora grew into an adult in Orlando, Florida, beginning his life again in the United States with his parents.

In 2010, Wiewiora graduated from the University of Central Florida with an Honors in the Major degree in English. He dedicated himself to The Florida Review as an assistant editor while completing his thesis, attending a close-knit writing group and crafting espresso drinks at a corporate coffeeshop. Wiewiora’s time at UCF prepared him to earn a Master of Fine Arts degree in Creative Writing and Environment from Iowa State University, where he also joined the masthead of Flyway: Journal of Writing and Environment as the managing editor.

Wiewiora’s travelogue memoir, The Distance Is More Than an Ocean (Finishing Line Press, $14.99), encompasses so much of his life in such a small space—like a poem, but not quite. Here, readers get the chance to open this book like a gate to a duplex with halves in two countries, observing one human being, both as a boy and as a man, discover his voice. In this memoir, an adult Wiewiora wisely and patiently questions his memory, but at all ages, he courageously seeks something inside of himself, something like belonging, but deeper. As a former Florida Review intern and UCF alum myself, I was pleased to interview Chris Wiewora about this work.

Ashley Inguanta: The Distance Is More Than an Ocean is a beautiful book. I can feel the water leading me through young Chris’s story, from his mother soaping up her hand injury, to the swimming pool at the Polish school he attended, to the rain pouring on his older self and his aged father. Young Chris wishes to return to West Virginia and this wish somehow leads him down a path that unites his Polish and American pieces.

Ashley Inguanta: The Distance Is More Than an Ocean is a beautiful book. I can feel the water leading me through young Chris’s story, from his mother soaping up her hand injury, to the swimming pool at the Polish school he attended, to the rain pouring on his older self and his aged father. Young Chris wishes to return to West Virginia and this wish somehow leads him down a path that unites his Polish and American pieces.

There are so many moments of joining in this travelogue memoir. The first moment of joining I noticed is the poem that opens the book, “Patching up the Past with Water” by James Seay. Tell me about how this connection to Young Chris’s journey originated. When did you read this poem, and when did it strike you how deeply it connects with your memoir?

Chris Wiewiora: My undergrad poetry thesis adviser at UCF, the poet Judith Hemschemeyer, gave me books. Every week I came to her office and she would read a poem or two of mine, mark the pages with blue pen (apparently less harsh than red), and then send me off with a book off the shelves lining an entire wall. Hemschemeyer (I could never call a woman nearly as old as my grandmother by her first name) was in her final years of teaching and she was passing along the treasures she had collected; she didn’t hold onto her hoard. She gave me Seamus Heaney’s Death of a Naturalist, Yusef Komunyaka’s Neon Vernacular, and a signed copy of Czeslaw Milosz’s Bells in Winter. What gems! These were books of language meant for me to hear the world, voice, and the past.

Hemschemeyer gave me the gift of reading, which lasts much longer than the gift of writing—we learn more as writers from reading than from writing. Isn’t that the point of the workshop, to learn about our writing by reading others’ writing? Somewhere in all of those books, Hemschemeyer gave me Water Tables by James Seay. It wasn’t until I was in grad school at Iowa State that I connected deeply with the poem “Patching up the Past with Water.” From 2009 to 2013 or so that poem just sat between the book’s covers between so many other books on one of my shelves.

I had wanted to use an epigraph for my graduate thesis that was as true as what my friend Andrew Payton had in a Donovan lyric that encapsulated his novel, Blasting at Big Ugly, about resisting mountain top removal. I wanted something that considered the fluidity of memory; how it can be contained, but also acknowledging that it spills. I sat in front of my bookshelf and pulled out poetry collection after poetry collection, many from Hemschemeyer, until I opened up Seay’s book and the lines of that poem shone like quicksilver. I knew that that stanza would be the epigraph and through several changes of containers and spills of my manuscript that epigraph remained as the place for readers to begin.

AI: The Distance Is More Than an Ocean is structured in a way that feels like the ocean. We have multiple sections here that begin, pause and roll back, and then begin again. We move forward into modern-day Chris’s life in Orlando, writing essays among the palm trees and egrets; and then we move back to young Chris, wishing he could dive deep into reading and writing in English, all the while being strongly encouraged to learn Polish. The structure of this memoir feels anchored by beginnings. When did you start writing about your time spent living in Poland? What pushed you to continue?

CW: Death started and ended this exploration. In 1996, my maternal grandmother Almond died just before my parents moved our family from Warsaw, Poland, to Orlando, Florida. As a child, I poured the two moments—her death and our move—into the same container of memory. I didn’t open that memory for years.

In her poetry workshop, after some awful poems about losing my faith as well as some about Ted Hughes and Silvia Plath (I had gone through a breakup with a Christian girl), Hemschemeyer suggested I write about something particular, something about my family. I wrote a poem called “Hometown” set in Buckhannon, West Virginia, where my mother was born and where I was born—both beginnings. But the poem was about the small town and my grandparents and them both dead and buried where I was birthed. That poem felt like the first poem that only I could write.

But none of that poem was about my time spent in Poland, it was only about my maternal side. My paternal side was from Poland, where I also grew up and where we ended up returning for a father-and-son trip when I was in college. Hemschemeyer must have known that I had more to write and she kept encouraging me as my poems began to explore my father’s Polish neighborhood in Chicago and our Orlando suburb. Around this time I found out via my friend Tina Kopic about the Honors in the Major thesis that an undergrad could do at UCF. And so I started what would become a poetry collection titled Side by Side.

I began writing poetry as an undergrad, but by graduation I had begun to feel that I didn’t possess the craftsmanship with meter. I understood and could conjure imagery. I became more interested in truth—or at least, perceived truth—and actually, I began writing what would become The Distance Is More Than an Ocean with an essay that I thought was just a one and done requirement for the Honors College. In the essay, I wrote, “We moved back to the States, because my grandmother died.” My father, a copy editor, read my essay and gave it back to me with the word “because” circled with a question mark in the margin and then offered the replacement, “around the time.” I had poured the death of my maternal grandmother and our returning to the States from Poland—those two moments—into the same container of memory.

In graduate school I wanted to explore that dynamic: between the moment and the memory. I didn’t return to poetry. I began again in nonfiction—a genre defined by what it isn’t, instead of what it is. I wouldn’t yet figure out what my manuscript wasn’t until I wrote what it was. So, I overfilled the container of my graduate thesis, including essays about going back to Poland with my father as well as essays about West Virginia and Florida and my family’s Evangelical faith. During my defense, my graduate thesis chair and then later a university press editor told me that I needed to find a through line—a major narrative thrust—for my manuscript. I was told it was about my Polish grandmother who survived the Nazi slave camps; I was told it was about my parents’ Evangelical faith.

It wasn’t until after grad school, after my paternal Polish grandmother’s death, that I began what would become the final version of The Distance Is More Than an Ocean. I began writing my poems about family in 2008; I began again with my nonfiction about growing up and going back to Poland with my father in 2018. I wrote and re-wrote through a decade because I was captivated by my past—shaped by my grandmothers—and I wanted to distill it into a container, a way to hold onto something as slippery as memory.

AI: One of my favorite things about this book is how you explore your relationship with language. Young Chris’s connection to the English language feels sacred. I know you spent a great amount of time studying at the University of Central Florida with Judith Hemschemeyer (who is also a translator), Jocelyn Bartkevicius, and the late Jeanne Leiby. How have your Orlando teachers shaped you?

CW: My teachers—more like godmothers who gave me gifts of their practices—revealed the timeline of language.

Hemchemeyer gave me books. She gave me the gift of reading the past. She literally gave me her books from poets who cornerstoned modern cultures of poetry, for instance, Milosz and Polish poetry.

Jocelyn gave me insight. She gave me the gift of writing in the present, while considering the past. She understood how memory takes shape in the way we remember it.

Jeanne gave me literary magazines. She gave me the gift of publishing in the future. She valued the word that was read and the word that was written and knew the writing that would be read.

My first publication was an essay in South Loop Review—a now-defunct Chicago lit mag—that I had first read in the office of The Florida Review and that I submitted to during a break from my poetry, after taking all of Jocelyn’s classes, and after apprenticing with Jeanne.

AI: When returning to any memory, even your memories of studying writing at UCF, there are layers: The memory itself and the moment it originated. You remember a lot of details: The red tie your principal wore, the “puke-green” tiles around the pool at the Polish school. What techniques do you use to bring back these memories? Tell me more about your relationship with memory and nonfiction writing, especially as you moved from studying and writing poetry to dedicating yourself to prose.

CW: As a beginner writer, I had to discover the techniques that worked for me. I explored the senses in poetry. I don’t remember where I acquired this technique, but I call it a 5x5. On lined notebook paper, I would write the words taste, touch, sound, smell, sight with five lines between them. Then, I would imagine a moment—later, a scene—and I would write down the senses that came to my mind. I would list 25 sensory words and phrases, but I wouldn’t plan to use them all. I would circle the best—be it unique or expected or just my favorite that I wanted to return to—line from each sense. But I wouldn’t use those five different senses. Then, I would consider those five and cross out all but one.

Who knows if that one sense was the best? But the process of considering all of the senses in that moment was more important than what I might use. I’m a writer when I’m writing, but I had to get myself to start writing and sometimes that took 25 words or just one.

AI: Let’s roll back into the memoir itself, focusing on the scene where young Chris is turning nine. He is in Poland, and he is about to move back to the States with his family. Your parents were Christian missionaries in Warsaw. An ocean separates Poland and the U.S., but, as you write this memoir, the distance is more. Like the moon shapes the ocean waves and the ocean shapes the land, religion shapes many things about who we are. Can you tell us more about how your family’s faith has affected your relationship to these two places?

CW: In Warsaw, during the late ’70s until the early ’90s my parents served as Evangelical missionaries, meaning they told Polish people about Jesus. They served in Poland during Soviet Communism when being a missionary was illegal. My father had a “furniture business” as a cover for them being overseas. My mother said she was a student and took Polish classes, but only learned to speak in the present tense. After I was born in the States, they brought me to Warsaw where the capital was home, but church was family.

Both of my parents helped found the Warsaw International Church where I got to know Poles and Canadians and Koreans. I remember walking through the rebuilt old town. I remember the cement-gray days and the dots of dandelions like promises of spring sun. I remember checking our coats in the lobby. I remember the hymns sung by the Polish choir. I remember the pastor’s show-and-tell children’s sermon. I remember doodling on the bulletins. I remember eating kimbop and playing with kids when my mom did Bible studies. I remember drinking tea in pewter mugs that held glass cups. I remember a guy who showed us his prototype for a board game he called Flip-Flash, which was kinda like Bananagrams and Scrabble.

Flip-Flash felt like our move back to the States, to Orlando. My parents took us to University Carillon United Methodist Church, a nearly-mega church near the soon-to-be mega-university UCF. We drove along Lake Underhill when there were still cattle in the fields instead of storage units for overstuffed suburbs. We drove past the new Waterford Lakes and the still being built 408 expressway and an open lot where dirt bikes jumped from pile to pile. We parked under a lone tree in the goopy asphalt parking lot and then chilled under the air conditioner. We worshipped to a rock-n-roll band hailing Jesus and listened to a pastor preach into a handless mic. We held hands in the benediction with mostly white—non-specific European heritage people—and also Caribbean, Latin, and Hispanic families. Only I drank coffee, but we all ate donuts under the awning. The humidity sucked up into the rolling clouds that would crack open on our drive home back to Deerwood where there are no deer and not much wood.

AI: We learn in The Distance that the memory of West Virginia is important to young Chris, especially as he is longing for the English language in Poland. With desperation to return to the States—to return home—he remembers strawberry patches at his grandparents’ house, hills, their dog. When you wrote this memoir, or really when you write anything, you could say you are re-sparking that voice you couldn’t wait to use as a kid. Your Grandma Almond eventually paid for you to attend an English-speaking school in Poland. What would you like to say to her, now that you’ve published your first book?

CW: “Thank you; I love you.” I would say that over and over again.

But really more than me saying something I would want to hear her. I don’t remember Grandma Almond’s voice or her laugh or her songs. I only remember her face from photos. I can’t recall her smell, even though my mom says that she always wore Chanel No. 5. I can’t even remember her lap where I know she read to me. Again, I would want to hear her and I know that it would be as lovely as the trill of her favorite bird (also the mascot of Iowa State) the cardinal saying, “What-cheer, what-cheer!”

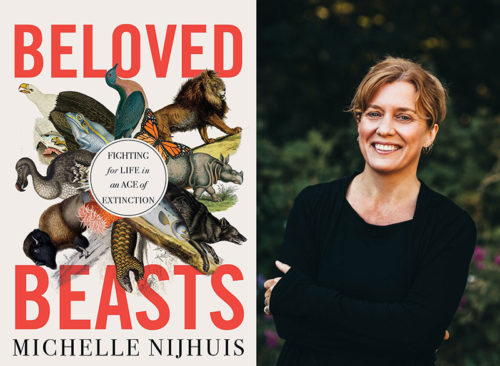

Jenny Price is a writer, artist, historian, and author of Flight Maps: Adventures with Nature in Modern America. Her new book Stop Saving the Planet! An Environmentalist Manifesto, is due out later this year. She lives in St. Louis, Missouri.

Jenny Price is a writer, artist, historian, and author of Flight Maps: Adventures with Nature in Modern America. Her new book Stop Saving the Planet! An Environmentalist Manifesto, is due out later this year. She lives in St. Louis, Missouri.

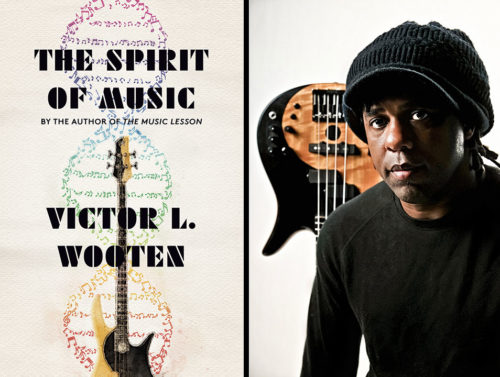

Sean McPherson is a host on Minnesota Public Radio's The Current, handling the request show, Radio Free Current, as well as co-hosting the hip-hop and r&b show, The Message, with Sanni Brown. He also co-hosts "The Warming House" on MPR News with Nina Moini and serves as the project manager and host for Purple Current, an HD2 station celebrating the musical universe of Prince. A recovering touring musician, McPherson has spent time playing bass with Dessa, Heiruspecs, and his solo project The Twinkie Jiggles Broken Orchestra. He lives in St. Paul with his wife and two children and is a proud graduate of St. Paul Central and the University of Minnesota.

Sean McPherson is a host on Minnesota Public Radio's The Current, handling the request show, Radio Free Current, as well as co-hosting the hip-hop and r&b show, The Message, with Sanni Brown. He also co-hosts "The Warming House" on MPR News with Nina Moini and serves as the project manager and host for Purple Current, an HD2 station celebrating the musical universe of Prince. A recovering touring musician, McPherson has spent time playing bass with Dessa, Heiruspecs, and his solo project The Twinkie Jiggles Broken Orchestra. He lives in St. Paul with his wife and two children and is a proud graduate of St. Paul Central and the University of Minnesota.