Uncategorized

KIM TODD and KATHRYN NUERNBERGER

Tuesday, April 27, 2021

5:30 pm Central

Crowdcast

Join Rain Taxi for a celebration of the women in history whose stories brought us where we are today—and the women today who write about them! Kathryn Nuernberger (The Witch of Eye, Sarabande) and Kim Todd (Sensational: The Hidden History Of America's “Girl Stunt Reporters," Harper) will discuss research, craft, and the many ways to tell a story long swept under the rug. Free to attend, registration required. We hope to “see” you there!

Books can be purchased either during the event or in advance from Magers & Quinn Booksellers in Minneapolis; just click the button below. Fun Fact: Any and all books you purchase via this link help support Rain Taxi’s virtual event series— thank you!

About the Presenters

Kim Todd is an award-winning author of books about science and history, including Tinkering with Eden: A Natural History of Exotic Species in America and Chrysalis: Maria Sibylla Merian and the Secrets of Metamorphosis. Her essays and articles have appeared in Smithsonian, Salon, Sierra Magazine, and Orion. Todd’s work has also appeared in Best American Science and Nature Writing 2015 and has been featured on NPR's Science Friday. She teaches on the MFA faculty at the University of Minnesota, and has given lectures at the Harvard Museum of Natural History, Yale University, the Getty Museum, the National Museum of Women in the Arts, and the Denver Botanical Garden, among other places. A senior fellow with the Environmental Leadership Program, Todd lives in Minneapolis with her family.

Kim Todd is an award-winning author of books about science and history, including Tinkering with Eden: A Natural History of Exotic Species in America and Chrysalis: Maria Sibylla Merian and the Secrets of Metamorphosis. Her essays and articles have appeared in Smithsonian, Salon, Sierra Magazine, and Orion. Todd’s work has also appeared in Best American Science and Nature Writing 2015 and has been featured on NPR's Science Friday. She teaches on the MFA faculty at the University of Minnesota, and has given lectures at the Harvard Museum of Natural History, Yale University, the Getty Museum, the National Museum of Women in the Arts, and the Denver Botanical Garden, among other places. A senior fellow with the Environmental Leadership Program, Todd lives in Minneapolis with her family.

Kathryn Nuernberger is an essayist and poet who writes about the history of science and ideas, renegade women, plant medicines, and witches. Her latest book is The Witch of Eye (Sarabande Books), which is about witches and witch trials. She is also the author of the poetry collections RUE, The End of Pink, and Rag & Bone, as well as a collection of lyric essays, Brief Interviews with the Romantic Past. Her awards include the James Laughlin Prize from the Academy of American Poets, an NEA fellowship, and notable essays in the Best American series. She teaches poetry and nonfiction for the MFA program at University of Minnesota.

Kathryn Nuernberger is an essayist and poet who writes about the history of science and ideas, renegade women, plant medicines, and witches. Her latest book is The Witch of Eye (Sarabande Books), which is about witches and witch trials. She is also the author of the poetry collections RUE, The End of Pink, and Rag & Bone, as well as a collection of lyric essays, Brief Interviews with the Romantic Past. Her awards include the James Laughlin Prize from the Academy of American Poets, an NEA fellowship, and notable essays in the Best American series. She teaches poetry and nonfiction for the MFA program at University of Minnesota.

TED RALL and PABLO CALLEJO

Tuesday, April 20, 2021

12 pm Central

Crowdcast

Join Rain Taxi for a special lunchtime conversation on politics, prose, and pictures with graphic novel creation duo Ted Rall and Pablo Callejo. Their new book, The Stringer (NBM Publishing), is an ode to when fact-based journalism mattered, set at an important turning point a few years ago, as well as a globe-trotting, action-packed, timely statement about how a society without a vibrant independent culture of reporting can degenerate into chaos. Don’t miss this chance to hear these trans-continental collaborators talk about their work!

Join Rain Taxi for a special lunchtime conversation on politics, prose, and pictures with graphic novel creation duo Ted Rall and Pablo Callejo. Their new book, The Stringer (NBM Publishing), is an ode to when fact-based journalism mattered, set at an important turning point a few years ago, as well as a globe-trotting, action-packed, timely statement about how a society without a vibrant independent culture of reporting can degenerate into chaos. Don’t miss this chance to hear these trans-continental collaborators talk about their work!

Books can be purchased either during the event or in advance from Magers & Quinn Booksellers in Minneapolis; just click the button below. Fun Fact: Any and all books you purchase via this link help support Rain Taxi’s virtual event series— thank you!

About the Presenters

Editorial cartoonist, essayist and graphic novelist Ted Rall grew up near the Rust Belt city of Dayton, Ohio. He won a scholarship to Columbia University in New York, which expelled him for academic and disciplinary reasons during the long hot summer of 1984. He has since become a widely-syndicated cartoonist, a Pulitzer Prize finalist, twice the winner of the Robert F. Kennedy Journalism Award and the author of more than twenty books, including a number of comics biographies covering figures from Bernie Sanders to Donald Trump. He returned to Columbia in 1990, where he graduated with honors. He lives in New York.

Born in Leon, Spain, 1967, Pablo Callejo can't remember when he started to draw or when he first felt the need to tell stories through pictures, but he took his time, since he didn't try to get published until he was 32. His critically acclaimed comics releases include Bluesman (written by Rob Vollmer) and The Year of Loving Dangerously (written by Ted Rall). After years of living in Madrid, he moved to Luxembourg.

NATE POWELL

Tuesday, April 13, 2021

5:30 pm Central

Crowdcast

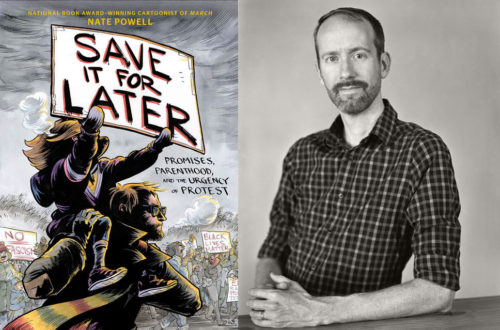

Join Rain Taxi for a night celebrating comics in context. In his new anthology of seven comics essays, Save It for Later: Promises, Parenthood, and the Urgency of Protest (Abrams ComicArts), graphic novelist Nate Powell addresses living in an era of what he calls “necessary protest.” As Powell moves between subjective and objective experiences raising his children—depicted in their childhood innocence as imaginary anthropomorphic animals—he reveals the electrifying sense of trust and connection with neighbors and strangers alike. Free to attend, registration required. We hope to “see” you there!

Books can be purchased either during the event or in advance from Magers & Quinn Booksellers in Minneapolis; just click the button below. Fun Fact: Any and all books you purchase via this link help support Rain Taxi’s virtual event series— thank you!

About the Author

Nate Powell is a National Book Award–winning cartoonist whose work includes civil rights icon John Lewis’s historic March trilogy, as well as Come Again, Two Dead, Any Empire, Swallow Me Whole, and The Silence of Our Friends. Powell has also received the Robert F. Kennedy Book Award, three Eisner Awards, the Michael L. Printz Award, Comic-Con International’s Inkpot Award, two Ignatz Awards, and the Walter Dean Myers Award. He lives in Bloomington, Indiana.

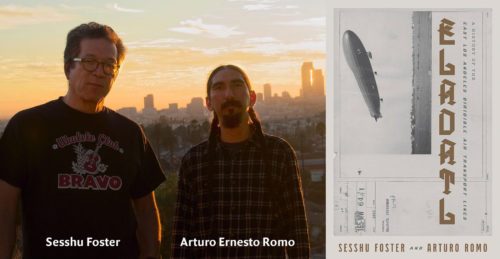

SESSHU FOSTER

and ARTURO ERNESTO ROMO

in conversation with Karen Tei Yamashita

Tuesday, April 6, 2021

5:30 pm Central

Crowdcast

Rain Taxi presents Sesshu Foster and Arturo Ernesto Romo discussing their stunning new novel Eladatl: A History of the East Los Angeles Dirigible Air Transport Lines (City Lights Books), in conversation with Karen Tei Yamashita. Hailed by Jonathan Lethem as “a superb and loving phantasmagoria that gobbles up real histories for breakfast and spits out the seeds," ELADATL tells the story of the little-known period of American air travel, when groups like the East LA Balloon Club were hard at work revolutionizing travel, with an aim to literally lift oppressed people out of racism and poverty. Via overlapping narratives, historic photographs, and recently discovered artifacts, Foster and Romo send up mainstream narratives and maybe the space-time continuum itself in this hybrid literary experiment of the highest order. Come discover with us!

Books can be purchased either during the event or in advance from Magers & Quinn Booksellers in Minneapolis; just click the button below. Fun Fact: Any and all books you purchase via this link help support Rain Taxi’s virtual event series— thank you!

About the Authors

Sesshu Foster taught composition and literature in East L.A. for over 20 years, and at the University of Iowa, the California Institute for the Arts, and the University of California, Santa Cruz. His work is published in The Oxford Anthology of Modern American Poetry, State of the Union: 50 Political Poems, and many other anthologies; his books include City of the Future, poetry, and Atomik Aztex, a novel. A celebrated writer, his literary awards are numerous: the American Book Award, the Asian American Literary Award in Poetry, the Believer Book Award, and more. He is based in Alhambra, CA.

Arturo Ernesto Romo was born in Los Angeles, California in 1980. His artwork, mostly collaborative mixed media works but also drawing, has been circulated internationally. Fluency, agency, and folly are central themes in his practice; he sees his artwork as a companion multiplier, folding folds, netting nets. His art-making is pushed through explorations on the streets of East and North East Los Angeles, which feed into an ongoing series of collaborations with writer Sesshu Foster. He is also based in Alhambra, CA.

Karen Tei Yamashita is the author of many critically acclaimed and award-winning works of fiction, including Through the Arc of the Rain Forest, Tropic of Orange, and I Hotel, all published by Coffee House Press. She received a US Artists Ford Foundation Fellowship and is Professor of Literature and Creative Writing at the University of California, Santa Cruz. Her most recent book of fiction, Sansei and Sensibility: Stories, was published in 2020.

Karen Tei Yamashita is the author of many critically acclaimed and award-winning works of fiction, including Through the Arc of the Rain Forest, Tropic of Orange, and I Hotel, all published by Coffee House Press. She received a US Artists Ford Foundation Fellowship and is Professor of Literature and Creative Writing at the University of California, Santa Cruz. Her most recent book of fiction, Sansei and Sensibility: Stories, was published in 2020.

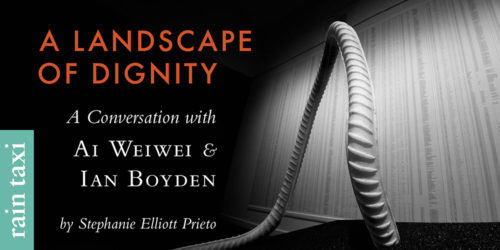

A Landscape of Dignity:

A Conversation with

Ai Weiwei and Ian Boyden

by Stephanie Elliott Prieto

It is a tradition for intellectuals to speak out against power. This is why artists and poets are so valued by society.

—Ai Weiwei

In 2015, the artist, writer, and curator Ian Boyden contacted renowned artist Ai Weiwei about exhibiting Ai’s work at the San Juan Island Museum in Washington state. The resulting 2016 exhibition, Ai Weiwei: Fault Line (a virtual tour of which can be seen here), presented three pieces from his ongoing investigation into the 2008 Wenchuan earthquake—a magnitude 8.0 quake that killed over 60,000 people, including 5,196 schoolchildren, in Sichuan province, China. Boyden hoped that among other things, the exhibition would raise awareness about the lack of preparation for a major earthquake in the Pacific Northwest. In the case of the 2008 Chinese earthquake, the destroyed schools had been built under government contract, quickly and cheaply, ignoring the government’s own building codes; the title “Fault Line” was thus a double entendre, referring to both the geological feature and the corruption that caused political leaders to fail to protect citizens. In China, the massive death toll was covered up by the government; even parents of the dead were intimidated into silence.

Working on the exhibition had a profound effect on Boyden, and out of it was born a body of poems. An entire wall of the exhibition was a monumental piece titled “Names of the Student Earthquake Victims Found by the Citizens’ Investigation”—and indeed, it listed the names of all the schoolchildren who died. As Boyden installed this wall, he began translating the meanings of the children’s names and sharing them on Twitter, but he found the names often defied a single translation, so he began to render them as short poems. Boyden spent a year translating the names and writing poems, and the result is now published as A Forest of Names: 108 Meditations (Wesleyan University Press, $15.95). The collection of spare poems meditates on language, translation, societal responsibility, and human dignity. It calls us to reflect on the faith we put in our governments and the immense power the state holds over our fragile human lives.

Working on the exhibition had a profound effect on Boyden, and out of it was born a body of poems. An entire wall of the exhibition was a monumental piece titled “Names of the Student Earthquake Victims Found by the Citizens’ Investigation”—and indeed, it listed the names of all the schoolchildren who died. As Boyden installed this wall, he began translating the meanings of the children’s names and sharing them on Twitter, but he found the names often defied a single translation, so he began to render them as short poems. Boyden spent a year translating the names and writing poems, and the result is now published as A Forest of Names: 108 Meditations (Wesleyan University Press, $15.95). The collection of spare poems meditates on language, translation, societal responsibility, and human dignity. It calls us to reflect on the faith we put in our governments and the immense power the state holds over our fragile human lives.

As Boyden’s book is the result of his long-term engagement with the work and thought of Ai Weiwei, I was privileged to correspond with both of these creators to discuss this project, cross-cultural artistic collaboration, and why “poetry is a dangerous act.”

EDITOR’S NOTE: Ai Weiwei’s responses were translated from Chinese by Ian Boyden. Stephanie Prieto is the publicist at Wesleyan University Press and serves on the Association of University Presses Committee for Equity, Justice, and Inclusion.

Stephanie Prieto: Do you think poetry and art play a role in understanding and upholding human dignity? If so, how do you view this role?

Ai Weiwei: Art and poetry are the most exceptional manifestations of all human emotional and cognitive activities. They cannot be replaced by rationality, science, or anything else. In today’s society, the spirit of art and poetry exists, but the modality of language has shifted. Every day, I witness ordinary people on Twitter expressing poetry unconsciously. Art is actually ubiquitous within reality, it is simply that this art is not necessarily made by artists from the academy. Regardless of whether it is poetry or art, both are important standards by which we can measure the spiritual quality of humanity.

Ian Boyden: I love this observation that the modality of language has shifted. This shift has allowed us to see and express ourselves in novel ways. When I first started this project, I was writing these poems on Twitter as a conversation with . . . well, mostly with myself. I felt like a firefly pulsing light in the darkness. Every day a few names would pulse from Weiwei’s account, and I would then pulse a poem in return. It was the conditions of Twitter that gave these poems the shape and rhythm they have. The 140-character limit required concision. But slowly, as the project grew and the novelty of the modality wore off, I began to understand that what I was wrestling with was something very ancient and central to what it means to be human: dignity. How do we describe dignity, how do we nurture it, protect it? In the names of these children, I saw dignity take the form of a vast landscape that is a profound expression of our shared world.

林萤

Forest of FirefliesFor a lifetime we pulsed

messages of light into the void, and waited,until we understood our message

was also our answer.

SP: Do you think the poems from A Forest of Names will find their way to Chinese readers? How do you think the work would be received?

AW: First of all, poetry itself is an intermediary, it’s a soliloquy, the poet thinking out loud to themself and in their own language. Poetry is a means to come face to face with language, history, and emotion, and as such it is a very personalized expression. If one writes poetry only to find readers, then poetry loses its most important layer of meaning. I don’t want to say Ian’s poems are unlikely to have many readers in China, but even a person who writes in Chinese in China doesn’t have many readers. Today, society is growing farther and farther away from poetry. The subject that Ian has addressed is considered politically sensitive. In addition, it’s related to part of my work and I myself am politically sensitive, which means my work is subject to censorship. You could say, the possibility of his poetry being openly circulated in China is zero. However, despite this, there is a literary magazine in China called Survivor, which is an underground publication. Some of Ian’s poems were published in this magazine, and so there are a few people in those circles who are aware of the existence of these poems.

Ian Boyden and Ai Weiwei reviewing an early draft of A Forest of Names at Ai Weiwei’s studio in Berlin, December 2017. Photograph by Zhipeng Liang.

SP: Ian, did you ever consider how Chinese readers might receive your work? Even if you didn’t necessarily think that would be a reality, did it affect your writing?

IB: How to translate these children’s names was, and continues to be, the subject of conversation with Chinese friends. They have been overwhelmingly supportive of this work, not just because the poems address an enormous humanitarian tragedy, the poems appeal to something very ancient and treasured at the very heart of Chinese linguistic reality—the primacy of names. At the center of Confucian philosophy is what is known as the “Rectification of Names”; for social harmony to exist, names must point to a specific truth. A is A; B is B. And yet, the opening line of the Tao Te Ching reads: The name that can be named is not the eternal name. Thus, the fabric of language must refer to truth, a truth that is the foundation of a healthy body politic, and, at the same time, names must transcend their own limits to embrace that eternal mystery that is each individual being. A power of poetry is that it both names and triangulates what exists beyond articulation.

And this leads to another subject at the heart of this project: How do we identify ourselves? How does identity relate to language? How does identity relate to memory? How does the relationship of the individual to the state affect our identity? Names are the very first forms of identity we are given, and in the case of these children, they are virtually all that remains. What happens to our identity when the state actively censors the names of the dead? What happens when it censors the grieving process? What happens to our identity when the state weaponizes the legal system, weaponizes language? What happens when the state actively creates false reality for its own end? To censor these names is to go to war with truth and dignity.

SP: Could you comment on the potential afforded by cross-cultural artistic practice in exchange, and how this is threatening to larger political bodies/states?

IB: A critical component of that potential is translation. Translation is the primary process by which a structure of thought born in one language can enter another. By its nature, this practice is disruptive, even subversive. Maybe not when we are trying to order a plate of food, but when it comes to a poem or a novel, or, say, trying to make sense of a monumental philosophy like Buddhism or Marxism, the effect can be overwhelming, reweaving the entire linguistic fabric. When language shifts in structure, it shifts what we are capable of perceiving, it shifts who we are capable of being, and thus upsets the balance of power.

AW: I think poetry is a dangerous act. In this regard, it’s just like art. Its potential and subversiveness are formidable, but first it must be allowed to exist. If systems of dissemination and/or censorship forbid its existence, then its subversiveness will disappear. This is why, with regard to art and literature, the establishment of fundamental human worth and freedom is the first requirement. I believe that in an open society this kind of discussion can exist, even if it may be trivial. People are entangled by various forms of popular discourse.

萬容

Myriad ContainerThe urn shattered,

ten thousand questions scattered

in the stone dust.

But each in its own way asked,Are we still one?

Beichuan County, Sichuan, May 2008. Photograph by Ai Weiwei. Image courtesy of Ai Weiwei Studios.

SP: What does it mean to you, to have an American author publish a book in response to your invitation to consider the names of the children killed in the Sichuan earthquake of 2008?

AW: What Ian has done is an exceedingly isolated and very poetic act. It is as if he suddenly discovered a pearl in the middle of a desert. Looking into this pearl, he sees clearly the universal value of human life and of our humanity. And yet in today’s world to hold these values has become a rare thing. It is very rare to find a person who sincerely cares about the suffering of other people, other ethnicities; to turn this kind of concern into poetic experience is even rarer still.

SP: Ian, how do you feel? Did you have any reservations, as an American responding to this horrific tragedy that happened to a nation that is often considered an adversary of the United States? Particularly a tragedy that is so politically sensitive?

IB: This question defies a simple answer. First, I would stress that I did not respond to this tragedy as an American but as a human. It was a tragedy that fell upon individuals and communities, first as buildings collapsed and then again as their government responded in such a horrific way.

There is a curious event horizon surrounding China, a pervasive illusion that what happens within its borders somehow bears no effect upon the outside world and vice-versa. It’s as if all the laws of causation and the dynamics of responsibility were somehow suspended. The cultural genocide of Tibetans and Uighurs—are those “politically sensitive” events truly internal affairs? An affront to one person’s fundamental rights, no matter where or who they are, affects us all. I responded to this tragedy as another human.

“Politically sensitive” is a way of acknowledging that fundamental rights are being violated. Taboo is the tool of the oppressor. The PRC has waged an all-out assault on language since the 1950s—destroying the plurality of languages across the country, severing linguistic continuity with the past by changing how the language is written, developing a vast system of censorship, constantly employing doublespeak, dictating what can and cannot be said, controlling the flow of information at all levels. Political language is used to undermine reality in the service of the few. Freedom of speech is not recognized as a fundamental right. Now, perhaps more than any time in history, the names need to be rectified.

SP: You have said of A Forest of Names: “I see this work as conceptual as can be. It is a beautiful and persistent effort of a poet’s heart and mind working together, dealing with our tragic reality.” In addition to considering the importance of the message in a piece of writing or other artwork, could you comment on the importance the method of approach, or aesthetics, in creating a piece of artwork?

AW: The nature of a work of art is determined by its feeling, its understanding, how it spreads through its creative use of language. If it abandons any of these fundamental levels, it cannot possess implicit meaning. Although artistic or literary acts are quite rare, they are an important part of the innate character of human beings. That such things appear or come into being, is, by itself, already an exquisite circumstance. The difficulty in this day then becomes how to disseminate this work of art or poem more widely. However, I stress that its coming into being is important in and of itself. This is important because it proves that people are beings that possess spirituality and compassion. It proves the possibility of a dialogue with an imagined world, an imaginary world that actually exists parallel with our own.

IB: The Chinese term Weiwei used here, translated as “implicit meaning,” is 含意, pronounced hányì. This is a very important aesthetic term in Chinese poetry. It literally means a meaning held in the mouth, unspoken and thus withheld from language. How to say something without saying it? This might be because it is too dangerous to say something directly. But it also speaks to a truth about language itself. One of the great ironies of language is that it often imprisons, or limits, the very idea one wishes to express. In Chinese poetry, there is a deep appreciation for generating conditions where meaning itself is granted freedom. So, we can see dignity is at play in this type of method, and this symbiosis of the spoken and unspoken was certainly a quality I sought to engage in the writing of these poems.

Detail of the installation of “Names of the Student Earthquake Victims Found by the Citizens’ Investigation” (2008–2011) by Ai Weiwei. Photograph by Ian Boyden.

SP: Ian, I read that you taught yourself Chinese by reading Ai Weiwei’s father’s poetry. That seems like fate.

IB: When I was nineteen, I went to China as a foreign exchange student. Before I left, a mentor of mine, the late poet Tom Crawford (1939–2018), gave me a bilingual volume of Ai Qing’s collected poems to take with me. My Chinese teacher at Nanjing University was so surprised when I showed her this book. Ai Qing (1910–1996) had only recently been allowed to return to Beijing from twenty years of exile in a labor camp in Xinjiang—the camp where Ai Weiwei was raised. I was young and naïve; at the time, it never occurred to me that this poet had a family, that he had a son named Weiwei. I really loved Ai Qing’s poems from the early 1930s that are filled with raw and ardent rebelliousness. I studied those poems—they were kernels around which the rest of my Chinese grew. Language is not truly separate from the speaker. Just a few words, a few vibrations of sound, can shape the subsequent patterns and conditions of the rest of our lives. I think much of life is spent trying to make sense of that. Ai Qing has a poem that speaks to this mystery, and I offer my own translation of it here:

Trees

One tree, another tree—

each towering and motionless,

each standing alone from the others—

the wind and air

tell of their distance apart.But enshrouded within the earth,

the trees’ roots stretch out

through the invisible depths

where their finest tendrils braid together.

There’s a visible landscape we all see. And there exists an invisible landscape that not only grounds us but is also a conduit of mind. Perhaps those roots reaching out through the earth are an image of fate, inseparable from curiosity and determination, empathy and fundamental dignity.

Click here to purchase this book

at your local independent bookstore

Rain Taxi Online Edition Winter 2020-2021 | © Rain Taxi, Inc. 2020-2021

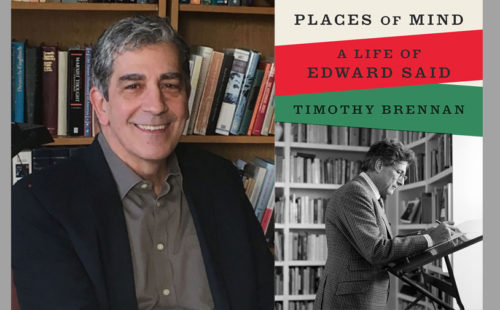

TIMOTHY BRENNAN

Tuesday, March 23,

5:30 pm Central — FREE!

Crowdcast

Join us for a special event about the many sides of Edward Said, the famed Palestinian literary critic, public intellectual, postcolonial studies trailblazer, political activist, and gifted pianist. Acclaimed American composer Nico Muhly, who was taught by Said at Columbia, will interview University of Minnesota professor and friend of Said's, Timothy Brennan, about his new comprehensive biography, Places of Mind: A Life of Edward Said.

Books can be purchased either during the event or in advance from Magers & Quinn Booksellers in Minneapolis; just click the button below. Fun Fact: Any and all books you purchase via this link help support Rain Taxi’s virtual event series— thank you!

About the Presenters

Timothy Brennan is the author of several books, including At Home in the World: Cosmopolitanism Now; Borrowed Light: Vico, Hegel, and the Colonies; and Salman Rushdie and the Third World: Myths of the Nation. His writing has appeared in The Nation, The Times Literary Supplement, and many other publications. He teaches at the University of Minnesota and has received fellowships from the Fulbright Program, the American Council of Learned Societies, the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft, and the National Endowment for the Humanities.

Nico Muhly is an American composer whose influences range from American minimalism to the Anglican choral tradition. The recipient of commissions from The Metropolitan Opera, Carnegie Hall, and others, he has written more than 100 works for the concert stage, including Marnie (2017), which premiered at the English National Opera. Muhly is a frequent collaborator with choreographer Benjamin Millepied and, as an arranger, has paired with Sufjan Stevens, Antony and the Johnsons, and others. He studied at Juilliard and Columbia, and lives in New York City.

Nico Muhly is an American composer whose influences range from American minimalism to the Anglican choral tradition. The recipient of commissions from The Metropolitan Opera, Carnegie Hall, and others, he has written more than 100 works for the concert stage, including Marnie (2017), which premiered at the English National Opera. Muhly is a frequent collaborator with choreographer Benjamin Millepied and, as an arranger, has paired with Sufjan Stevens, Antony and the Johnsons, and others. He studied at Juilliard and Columbia, and lives in New York City.

CLAUDIA ZOE BEDRICK and PING ZHU

Tuesday, March 16, 2021

5:30 pm Central

Crowdcast

Join us as we present a conversation with the publisher of Enchanted Lion Books, Claudia Zoe Bedrick, and the illustrator of their new release The Snail with the Right Heart, Ping Zhu. These two creative visionaries will discuss the joys and challenges of indie publishing for the children's market, as well as their individual paths to creating their art. The conversation will be moderated by author, essayist, and editor Bruce Handy. Free to attend, registration required. We hope to “see” you there!

Books can be purchased during the event, or in advance here, from Magers & Quinn Booksellers in Minneapolis; click the button below.

About the Presenters

Claudia Zoe Bedrick is the publisher, editor, and art director of Enchanted Lion Books, an award-winning, independent publisher based in Red Hook, Brooklyn. Her sense of hope is nourished every single day by the unfettered minds and creativity of children everywhere, and by looking out and up into the sky each morning.

Claudia Zoe Bedrick is the publisher, editor, and art director of Enchanted Lion Books, an award-winning, independent publisher based in Red Hook, Brooklyn. Her sense of hope is nourished every single day by the unfettered minds and creativity of children everywhere, and by looking out and up into the sky each morning.

Ping Zhu is a small sentient speck in the Universe. Most days you will find her illustrating and running around in Brooklyn, NY. The Snail With the Right Heart is her second illustrated book with Enchanted Lion, following last year’s The Strange Birds of Flannery O'Connor. She believes in a full 8 hour sleep cycle for optimum recharge.

Ping Zhu is a small sentient speck in the Universe. Most days you will find her illustrating and running around in Brooklyn, NY. The Snail With the Right Heart is her second illustrated book with Enchanted Lion, following last year’s The Strange Birds of Flannery O'Connor. She believes in a full 8 hour sleep cycle for optimum recharge.

Bruce Handy is an author, journalist, essayist, critic, humorist, and editor. He is the author of Wild Things: The Joy of Reading Children’s Literature as an Adult (Simon & Schuster, 2017), and has worked as a writer-editor at Vanity Fair, Time, Esquire, and Spy. He has contributed to the New York Times Magazine, the New York Times Book Review, and the New Yorker, as well as other publications that don’t have New York in their titles, including The Atlantic and the Wall Street Journal. His first book for young readers, The Happiness of a Dog With a Ball in Its Mouth, will be released by Enchanted Lion later this spring.

Bruce Handy is an author, journalist, essayist, critic, humorist, and editor. He is the author of Wild Things: The Joy of Reading Children’s Literature as an Adult (Simon & Schuster, 2017), and has worked as a writer-editor at Vanity Fair, Time, Esquire, and Spy. He has contributed to the New York Times Magazine, the New York Times Book Review, and the New Yorker, as well as other publications that don’t have New York in their titles, including The Atlantic and the Wall Street Journal. His first book for young readers, The Happiness of a Dog With a Ball in Its Mouth, will be released by Enchanted Lion later this spring.

The Selected Poems of Tu Fu

Expanded and Newly Translated

Expanded and Newly Translated

Tu Fu

translated by David Hinton

New Directions ($18.95)

by John Bradley

“The original is unfaithful to the translation,” Jorge Luis Borges once wrote, making light of the eternal debate about the reliability of translations. Certainly this thorny topic arises once again with The Selected Poems of Tu Fu, as David Hinton also published a previous Selected Poems of Tu Fu thirty-one years ago (New Directions, 1989). Hinton, a well-known translator of classical Chinese texts, has revised the poems in the earlier collection and included more; this is exciting news for poetry readers, though the new volume is not without some problems.

Tu Fu (712-770 CE) is considered one of the greatest poets of China. He lived during a period of cultural richness in the T’ang Dynasty, but he also witnessed a devastating civil war, and was often ill during this time of turbulence, suffering from asthma, malaria, and rheumatism. Despite social unrest, poor health, and dire poverty, however, the last decade of his life was when he wrote most of his poems. While many translators have tried their hand at rendering Tu Fu into English, a new attempt is always welcome given the challenges of translating Chinese (no articles or pronouns, for example). Hinton certainly brings years of expertise to the task, having also translated the I Ching and Tao Te Ching, as well as works by Chuang Tzu, Confucious, Mencius, Li Po, and so many others. He recently added to his voluminous oeuvre Awakened Cosmos: The Mind of Classical Chinese Poetry (Shambhala, 2019), where he studies in depth nineteen poems of Tu Fu.

One of the most striking aspects of the new Selected is Hinton’s belief that Tu Fu was deeply influenced by Taoist/Ch’an (Zen) Buddhism. These teachings gave Tu Fu the perspective, in Hinton’s words, of “the empirical Cosmos as a single living tissue that is inexplicably generative.” He even refers to Tu Fu as a Taoist/Ch’an “adept,” which contrasts with his previous notion of Tu Fu as a poet steeped in a Confucian worldview that valued service and ethics. While Hinton may be correct about the influence of Taoist/Ch’an Buddhism on Tu Fu, unfortunately his use of philosophical terminology often feels imposed upon the poems. Take the opening line of “Yin-Dark Again”: “Dark-enigma winter bleeds through dark-enigma’s yin-dark / frontiers.” In Hinton’s notes, he explains that “dark-enigma is functionally equivalent to Absence—the generative, ontological tissue from which the ten thousand things spring—but Absence before it is named.” While it’s helpful to have this mysterious term defined, it would be even better if the translator had found a way to make the unwieldy term function in the poem itself, rather than as a philosophical concept that sends the reader to the back of the book for a rather dense explication.

Other problems in this translation also arise. As mentioned, there are no articles in the Chinese, so it must be tempting for a translator to avoid them altogether. But this solution isn’t ideal, as can be seen in this four-line “Cut-Short Poem”:

River sweeps moonlight across stone.

Stream empties mist-fringed blossoms.Perched birds understand ancient Way.

Sails pass, spend night in whose home?

The missing articles, for some readers, will have the whiff of an Orientalist impulse to use broken English in an attempt to sound like a non-native speaker. To say “The river sweeps moonlight” may sound more prosaic, but it avoids inadvertent stereotyping.

Some readers will also feel confused by Hinton’s literal translations of place names. For example, the city of Ch’ang-an, now called Xian, in Hinton’s new translation becomes “Peace-Perpetua,” and Chengdu becomes “Altar-Whole City.” While these literal translations perhaps sound more poetic, they make the poems feel unlocated. In his 1989 Selected, Hinton used the transliterated names of towns in the poems, as when he opens “Moonlit Night” with the line “Tonight at Fu-chou.” Contrast this with his revised translation of the same line: “Tonight at Deer-Altar.” The new version sounds like the location of a religious rite, rather than a city.

As Tu Fu has been much translated, some readers may want to compare Hinton’s new translations with versions by others as well. Here is Hinton’s “Thoughts Brimful: Cut-Short Poems,” number 9, in its entirety:

Delicate willows swaying outside my door—slender,

graceful as a girl’s waist at fifteen: who was it sayingJust another morning, same as ever? That wild wind

broke them down: the longest, most elegant branches.

And here is Kenneth Rexroth’s translation of the same poem, which he entitles “The Willow,” in One Hundred Poems from the Chinese (New Directions, 1971):

My neighbor’s willow sways its frail

Branches, graceful as a girl of

Fifteen. I am sad because this

Morning the violent

Wind broke its longest bough.

Rexroth’s version offers a clearer poem, though he takes the liberty of adding “I am sad” and does not include the “Who was it” question Hinton does. Still, Rexroth created a poem in English that has focus and grace, which—however difficult—should be the translator’s aim.

Hinton is at his best when he avoids philosophical terminology and provides Tu Fu’s voice and sensory detail, as seen in “Returning Late”:

Past midnight, eluding tigers on the road, I return

home in mountain darkness. Family asleep inside,I watch the Northern Dipper drift low to the river,

and Venus lofting huge into empty space, radiant.Holding a candle in the courtyard, I call for more

light. A gibbon in the gorge, startled, shrieks once.Old and tired, my hair white, I dance and sing out:

goosefoot cane, no sleep . . . Catch me if you can!

Though some might argue that the phrase “goosefoot cane, no sleep” should come before “I dance and sing out,” the poem stays grounded in the incident and the emotion. Tu Fu’s sense of playful foolishness shines through.

Perhaps it was poverty and bad health that made Tu Fu feel so vulnerable and so empathetic in his poems. He speaks not as a scholar, but as one who has witnessed the consequences of war on his fellow citizens. The poem “Asking Again” shows his awareness of the cost of war even on those far from battle:

Couldn’t we just let her filch dates from the garden?

She’s a neighbor, childless and without food, alone:only desperation would bring her to this. We should

treat her like family. It will ease her fear and shame.She knows us now, but strangers from far away still

frighten her. A fence would only make things worse.Tax collectors hound her, she says, keeping her bone

poor. How suddenly war rifles thought, leaving tears.

The resonance of the line “A fence would only makes things worse” shows readers how a poem written over a thousand years ago still speaks to us today. Tu Fu’s vulnerability is even more touching in the poems about his family, as seen in the closing lines of “Hundred Worries Gathering Chant”:

and when I return home, everything’s the same as ever:

cupboards empty, old wife sharing the look on my face.Silly kids, still ignorant of the ritual esteem due a father:

angry, screaming at the kitchen door, they demand food.

Over and over, it’s Tu Fu’s humanity and humility that make him worthy of the attention he continues to attract from generations of translators and readers. The new Selected only confirms this. Even with its problems, Hinton’s book deserves wide readership, as Tu Fu’s poetry offers so much: insight into a historical period, into a prominent nation and culture, and, most of all, into the human psyche. One may wonder, though, if the poet’s “Catch me if you can!” doesn’t stand as a call to future translators of his work. While Hinton’s new Selected is a cause for celebration, let’s hope that following translators bring their craft to give us yet new versions of the poetry of Tu Fu.

Click here to purchase this book

at your local independent bookstore

Rain Taxi Online Edition Winter 2020-2021 | © Rain Taxi, Inc. 2020-2021

The Bangtail Ghost

Keith McCafferty

Keith McCafferty

Viking ($26)

by Don Messerschmidt

Keith McCafferty’s latest novel, The Bangtail Ghost, begins with a strange and violent death at the end of a forest road in the mountains of Montana. Blood in the snow, a puma whisker, paw prints, and drag marks lead to the remains of a woman’s mutilated body. If these first few clues were all there were, Sheriff Martha Ettinger might have declared it an unfortunate misadventure, but when the mystery deepens with screams in the night, a flickering light, and a growing list of missing persons, she hires the private detective Sean Stranahan to help sort it out.

After the dead woman’s profession and some of her clients are exposed, what looked at first to be a straightforward case of mountain-lion-kills-innocent-woman turns into a conundrum. Then, with evidence of more than one mountain lion and human interference, a professional tracker with hounds is engaged to help Stranahan hunt them down, only to wonder if they, too, are being stalked.

Once you’ve read a Keith McCafferty mystery you’ll recognize the style, a rapidly rising drama that turns into a whopping good whodunit—or in The Bangtail Ghost, a what-dunit. The author is a master at writing tense, gripping page-turners. His Montana-set Westerns, however, are unlike the classics of Louis L’Amour or Zane Grey. Rather, starting with his first novel, The Royal Wulff, McCafferty has written compelling, contemporary, and adventurous mysteries. Each plot reflects the author’s combined expertise as a Field & Stream magazine editor, an angler, a hunter, and an expert on camping, hiking, backpacking, and fishing. Adept at weaving passion into his stories, it is no surprise that he has become known as the founder of a unique sub-genre known as “fly-fishing noir.”

McCafferty’s characters are modern, earthy Montanans whose lives reflect openness and good humor—and, at times, darkness. They have come from all walks of life to settle in the changing American West. They live, talk, walk, hunt, fish, drink, and shoot pool together, and occasionally get caught up in strange doings. Sean Stranahan, the series’ protagonist, is also a talented painter and a popular fishing guide who demonstrates while working his cases both where to cast the best hand-tied flies and how to entertain readers.

Each of McCafferty’s novels reflects his own experiences in the wild, combined with in-depth research to sustain realistic plots. For example, Cold Hearted River (sixth in the series) involves the (fictitious) discovery of a trunk full of fishing gear and some early writings that once (in real life) belonged to Ernest Hemingway. A Death in Eden (the seventh) derives from actual public outcries over a proposed copper mine in the head-wa¬ters of the Smith River and the likelihood of it spewing environmental destruction. In The Bangtail Ghost (the eighth novel), McCafferty reveals his immense knowledge of mountain lions that sometimes become man-eaters, intermixed with some nefarious activities attributed to one or another of the novel’s shady characters.

It’s been said that all books are mysteries, and Keith McCafferty’s award-winning Westerns prove it. His books are worth reading because what lures us all is something the tracker points out to the private eye while stalking and being stalked in the mountains. “We like a yarn,” he says. Indeed!