Interviewed by Lawrence Welsh

About twenty-four years ago, an English professor in West Texas named Tom Casey gifted me his first edition copy of Memory Babe: A Critical Biography of Jack Kerouac by Gerald Nicosia. I knew of the book, but I had never read it. Over the years, I’ve pored over it time and time again. It’s a seminal text and a touchstone into the world of the Beats and Kerouac.

A few years later, Lummox Press out of Southern California started publishing my work in its magazine and would eventually publish two of my books. Through Lummox, I met a wide range of writers, including Nicosia, whose “Remembering Bukowski on the Fourth of July” recently appeared in a Lummox anthology called Last Call, Chinaski! An Homage to 70 Years of Bukowski’s Influence on Culture and Writing.

On a whim, I contacted Nicosia over Facebook, and he wrote back. We’ve enjoyed an epistolary relationship ever since, so it was easy to conduct an interview regarding his latest work, Beat Scrapbook (Cool Grove Press, $19.95). In essence, Beat Scrapbook provides a powerful portrait of a wide range of voices that Nicosia knew. Many of these were not only steeped in Beat and post-Beat culture but also became touchstones for both a social and literary revolution.

Lawrence Welsh: Of all the Beats in your Scrapbook, who has returned the most in dreams?

Lawrence Welsh: Of all the Beats in your Scrapbook, who has returned the most in dreams?

Gerald Nicosia: I haven't dreamt of many of the people in Beat Scrapbook; I was able to count only six that have appeared in dreams. So I'll recount a little bit about those six. The most interesting dream story is of Jack Mueller. Jack was in the generation between the Beats and the post-Beats—he was born in 1942, and my arbitrary cutoff for the Beats is people born before 1940. The post-Beat writers were mostly born in the 1950s, though a few, like myself and Neeli Cherkovski, were born in the later ’40s.

Mueller deserves his own book—he was a very brilliant and innovative poet, tall and balding and with spectacles, with the look of a German mad scientist. He had been in India in the Peace Corps, he'd taught sailing in New Orleans, he was a man of innumerable gifts, but when I knew him he was supporting a wife and baby daughter by selling hats at a kitschy North Beach storefront called the Schlock Shop. Jack had more influence on my early poetics than almost anyone, but the thing he taught me most forcefully was that a writer has to keep an open heart toward everyone.

In the 1990s, our lives went separate ways. I moved to L.A. with my first wife, a lawyer and art dealer. Jack moved down to Texas to direct a museum, so that he could care for aged, ailing parents. I eventually got back to San Francisco with a second wife, but Jack stayed in Texas until both his parents had died. That allegiance to his parents was all the more remarkable since his father was a devout Christian minister, and Jack was an atheist! His marriage more or less fell apart with that long residence in Texas, and he ended up retiring, afterward, to a little shack in the Colorado mountains. We still corresponded occasionally by email.

Anyway, I never dreamed of him until December of 2016, and then I had a very strange and vivid dream of him. He and his wife and daughter were having a picnic on a blanket in the middle of Washington Square Park in North Beach—the park Richard Brautigan is pictured in, in front of the Benjamin Franklin statue, on the cover of one of his early books. Weirdly, there was a train track running through the middle of the park, which is not there in real life. A locomotive engine was suddenly rushing at us, and Jack helped pull me out of the way.

The dream came with a strong feeling that Jack was in danger, and I felt I needed to get in touch with him right away. But his email address no longer worked, and none of the mutual friends I contacted could give me his address or phone number. A few months later, I read of Jack's death in the San Francisco Chronicle. I subsequently got in touch with his daughter Kristina and learned that he had collapsed at the end of December, on virtually the day I had dreamed of him. He was taken to the hospital and diagnosed with lymphoma, which killed him at the end of April.

I've been something of a psychic all my life, but that dream, which I wrote down in my journal, is one of the strongest proofs I can offer that human beings are capable of extrasensory perception.

In one of the poems in Beat Scrapbook, I write of a recurring dream about my mother and myself—a dream I still have sometimes, in slight variations. My dad died when I was 22, and for many years I lived with my mother, and we were always moving between Chicago and California, because she was terribly lonely in her later years (she was 40 years older than me). Between substitute teaching and freelance writing, I never had much income, and her pensions kept the rent paid, but we were always financially struggling. That dream records the desperate need for a real, permanent home we both felt, and the sense that the world is a cold and dark place, from which love and companionship are the only real refuge. I've now lived in the same home for 27 years, but that fear of homelessness, fear of living in an alien world, can still chill me deeply in dreams.

I've dreamed a few times of Jack Kerouac, whom I never met in actuality, but the dreams are a measure of how much he has haunted my adult life. When he appears, I'm always excited and relieved, maybe even overjoyed, and my overriding feeling is a kind of exclamation: "So now I'll finally know what you're really like!"

Jan Kerouac, whom I loved, appears in dreams from time to time. She's always very much like in real life: gentle, troubled, perpetually in need of help. In a few of the dreams we're having some kind of romance, which was cut off quite early in real life. Back in our twenties, when she saw me starting to exhibit serious feelings toward her, she warned me quite bluntly, "You're not my type—you're too nice. I don't like nice guys! I'm a bad person, and I chase guys who end up abusing me." The only thing that was really bad about her was that she hurt herself a lot. She felt she didn't deserve love or happiness because her father had rejected her. It was only at the very end of her life that she began to blame him, justly I believe, for the disaster her life became.

Ntozake Shange, whose biography I'm working on, appears sometimes—needy and lost and asking my guidance, as she did in real life. Like most of these others in my dreams, she was someone who touched me deeply, not least because she was so self-deprecating, so unsure of her own worth, when it was clear to me and a lot of others that she was a stone-cold genius.

Finally there's Charmaine, who was a lover of mine—totally wild, unbelievably brilliant, and drop-dead beautiful. The actual details of much of her life would be cause for indictment and arrest, though like that character in Vanity Fair, she eventually made her way to wealth and respectability, and (as far as I know) now lives on an estate in Hawaii. We haven't communicated in years, yet when I dream of her, we're still in the midst of a passionate and troubled love affair. Funny thing is that in my dreams her hair is still jet-black and her face is still that of a woman in her early twenties, though in real life she's now a senior citizen.

LW: Which dead and undervalued Beat is most worthy of new scholarship and reassessment?

GN: That's a fraught question, because there are so many wonderful Beat writers who got lost in the shadows caused by the bright light shone on the central writers such as Kerouac, Ginsberg, and Burroughs. Philip Whalen, Ray Bremser, Janine Pommy Vega, Lenore Kandel, Jimmy Ryan Morris, and Jerry Kamstra are just a few of the scores of absolutely original writers inspired by the Beat movement. But of the core Beat writers, I'm most astonished by the scant attention and critical scholarship accorded to Gregory Corso. I consider him the greatest poet of the Beat movement, and Ginsberg also considered him as such. He was, as you will gather from my poems about him, the quintessential bad boy, 86-ed from more bars, restaurants, and friends' homes than most people enter in a lifetime. But it's hard to account for the neglect of Gregory's work just because of his obstreperous conduct and nasty tongue. Even while he was alive, he realized, and complained of the fact, that people were not taking his poetry seriously. Maybe, ironically enough, there was still class and status bias operating in the Beat ranks, or at least among the people who study them. Gregory was a true street kid and an ex-con who'd spent three years at Dannemora State Prison in New York, while Kerouac and Ginsberg, for all their antics, had gone to Columbia University, and Burroughs had graduated from Harvard! To Kerouac's credit, he compared Corso with Caruso and Sinatra in his introduction to the first edition of Gasoline—which for Kerouac was high praise.

LW: Many of the Beats sought transcendence through daily rituals of meditation and prayer. Do you follow a spiritual path or paths? If so, what is your practice and how does it interact with your writing?

GN: I was raised Catholic, and though I have many differences of opinion with the Church, I am still deeply Christian. I don't see how anyone who's read Church history can believe in Papal infallibility, though I like Francis a lot. Pope Francis, in his concern for the poor and for outcasts, does honor to St. Francis of Assisi, my favorite saint. I don't go to Mass anymore, but I still like to pray in Catholic churches, especially when they're mostly empty, and I still light candles for the living and the dead. I like what Kerouac said, that all writing is a form of prayer, or should be.

LW: Who is the most important Beat scholar, and what have they done to help further the discourse?

GN: I take it you're excluding me? I'm not wholly joking, since in all honesty I don't know a great many scholars who have devoted a lifetime to studying and promoting Beat writing to the degree that I have. There are some people who have devoted a lifetime, or half a lifetime, to making money off the Beats, and in a Christian spirit I'll forego naming those people. But I think to do important work on the Beats, it helps to share their spiritual dimension, their heartfulness, and also their creative dimension—and not a lot of people can fill those shoes. It also helps, if one wants to explicate or promote the Beats, if one can write. Nothing I detest more than academic gobbledygook—that's one of the reasons I left academia.

A scholar I really admire—and the guy can really write—is Gregory Stephenson, an American who's spent most of his life teaching in Denmark. His book The Daybreak Boys is one of my all-time favorite books on the Beats. The late Bruce Cook's book The Beat Generation is still one of the best overviews of both the Beat movement and its key writers. And Tim Hunt, who wrote Kerouac's Crooked Road, has done some of the most original textual study of Kerouac.

Curiously, all of those critics moved on from the Beats in their later work. But maybe one has to take a break from the intensity of the Beats, which, after all, killed many of the Beats themselves before their time. I shifted at least part of my own focus, for two decades, to veterans, who have their own intensity.

One scholar who's been almost completely forgotten is Joy Walsh, who gave an incalculable boost to Kerouac study by publishing an informal Kerouac journal called Moody Street Irregulars for about fifteen years, from 1980 to 1995. She threw open her pages to everyone from punk musicians and unknown street poets to highly-honored academics, and the result was a publication that actually gave a well-rounded portrait of that most complex man and writer. I hope someday somebody will publish the collected issues of Moody Street in a single volume.

LW: Why is Jack Kerouac still relevant and important?

GN: Now you're asking me to write another book! There are as many reasons to read Kerouac as there are readers. No writer has ever given such a complete record of a human life from birth to the brink of death. Nor is there a better picture, I think, of what it meant to be alive through the Great Depression and the aftermath of World War II than in the many novels of the Duluoz Legend. And, of course, if you're a poet, there's an endless tutorial in modern poetry in Mexico City Blues. In prose, Kerouac's spontaneous bop prosody is one of the main streams that fed into the river of postmodernism. And then there's the whole thing of Kerouac's sort of pop psychology guide to individualism and finding one's true identity. I am still running into people who tell me, "Kerouac changed my life" or "Kerouac gave me permission to be who I am today."

LW: Your father was the child of Sicilian immigrants who settled in Chicago, and your mother's father was an immigrant from Czechoslovakia. What hold, if any, did the old world have on you? Does it still affect your life?

GN: I still swear in a combination of Sicilian and Czech—that ought to tell you something! A foreign language was spoken in many of the households of friends and family when I was growing up. My Sicilian grandmother, who lived with us till I was six, never learned to speak English. There were parts of Chicago, probably still are, that were like suburbs of Warsaw. Chicago was one of the great U. S. cities built by immigrants. I guess you could say that of a lot of U. S. cities, but the thing about Chicago was that the immigrants still held fiercely to their original identity. There was Greektown, Andersonville (where the Swedes lived), and the Italians clustered in Hell's Half Acre around Taylor and Halsted. When you'd start to tell somebody about a new friend you'd made, the second question you'd receive—after, "What's his name?"—would be, "What's his nationality?" All that is still with me, a world of us and them, of inside and outside. I'm sure that point of view helped prime me for the Beats, who celebrated their role as outsiders, and who constructed their identities out of being different rather than fitting in.

LW: Tell us about your writing routines over the decades. Have they changed? Do you employ different practices for poetry and nonfiction? Do you work on a typewriter or computer? What is your relationship to paper, pens and pencils?

GN: I came to computers late, in 1990, out of necessity—when it became clear that whether you were writing for newspapers or big publishing houses, everyone wanted digital copy. Memory Babe was written on an old Smith Corona electric typewriter. I still have my IBM typewriter and sometimes write letters on it. I also still write letters by hand—I like pen, preferably a gel pen or rollerball, not pencil. And I've kept a handwritten journal for going on 55 years. Prose comes more easily to me on a keyboard, but I prefer writing poems by hand. I like the communication of hand with ink and paper. I like the feel and smell of paper, the sound of a pen scratching out words. Writing is still partly a tactile art for me, but it's also a sound art. I read my work aloud, to myself, especially when I'm revising. The sound of what I'm writing, the way the words fit together, is important to me in prose as well as poetry.

LW: What advice can you give to new or struggling writers who are trying to come up in the life?

GN: I think of what Ntozake Shange told me: "You'll never become a serious writer if you start out expecting to make a living from it." She said she knew from the start that she'd need to have a way of making a living that was separate from her art. It was because she gave herself the freedom to write noncommercially that she was able to write a masterpiece like For Colored Girls Who Have Considered Suicide/ When the Rainbow is Enuf, which eventually brought her a small fortune. That's pretty much the same as Kerouac's "vow of poverty." If you want to be a writer as your career, fine, there are plenty of companies that need people who can write. But if you want to be a serious writer, you write for an audience of one, yourself. Odds are you won't ever make a living from it, or at least much of a living, but you will know the joy of entering a new world every time you sit down to write. It's what Bukowski meant when he wrote, "if you're going to try / go all the way / there's no other feeling like that. / you will be alone with the gods / and the nights will flame with fire."

LW: Can you tell us about one of the most difficult periods of time you faced as a writer and how you overcame the challenges?

GN: Again, this requires writing a book. And I did write one, Kerouac: The Last Quarter Century. My support for Jan Kerouac's right to reclaim her father's estate got me blacklisted by the people who had stolen that estate, as well as by the publisher, the biggest one in the English-language world, that publishes material from that estate. For years I had a major literary career—I was published by Grove Press, Viking, Penguin, Random House, Carroll & Graf, and University of California Press, among others. Then I was blacklisted, and I ended up with tiny publishers like Host Publications and Coolgrove Press, and eventually I had to self-publish most of my work. It's been a long fight to keep my work as a writer available to the public, and that fight is still going on. There is no secret, or if there is, it's just in the words of a great painter I knew in San Francisco, Robert Newrock, who lived in the Tenderloin most of his life, and relied on the charity of his friends to survive. He told me a long time ago: "Don't ever give up!" I wrote a poem about him called "The Ghost of Swade Bonnet," which is in my first book of poetry.

LW: What place or spot in America speaks the deepest to you?

GN: Chicago will always be my home, and West Flournoy Street, where my father grew up with his widowed Sicilian mother and three siblings, will always be sacred ground to me, even though the original buildings are gone and it’s mainly public housing now. The Church of Notre Dame is still there, where my father collected water that had been dribbled over stones from Lourdes in France, from which he expected to see miracles. I feel those miracles under my feet every time I walk on Flournoy Street.

Click here to purchase this book

at your local independent bookstore

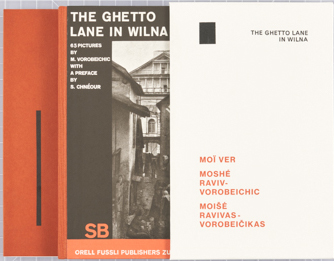

Sigutė Chlebinskaitė, Mindaugas Kvietkauskas, and Nissan N. Perez, eds.

Sigutė Chlebinskaitė, Mindaugas Kvietkauskas, and Nissan N. Perez, eds.

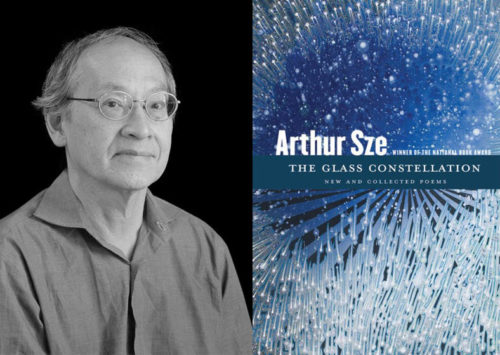

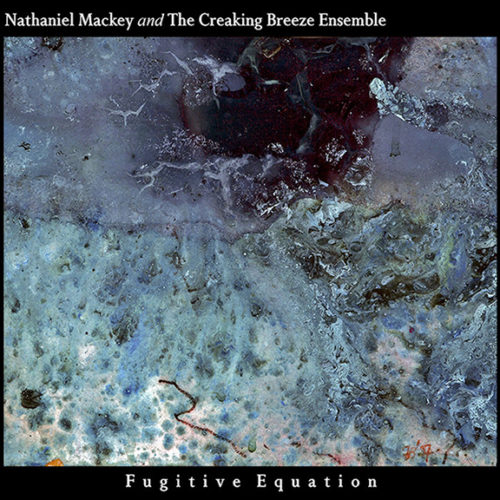

Nathaniel Mackey was born in Miami, Florida, in 1947. He earned his BA from Princeton University and his PhD from Stanford University, and is the author of numerous books of poetry, including the National Book Award-winning Splay Anthem (2006) and Eroding Witness (1985), which was chosen for the National Poetry Series. He has also published several book-length installments of his ongoing prose work, From a Broken Bottle Traces of Perfume Still Emanate, which critic David Hajdu described as “not simply writing about jazz, but writing as jazz.” Mackey cites poets William Carlos Williams and Amiri Baraka, in addition to jazz musicians John Coltrane and Don Cherry, as early influences in his exploration of how language can be infused and informed by music. Also known for his editorial work and critical bent, Mackey has coedited the anthologies Moment’s Notice (1993) and American Poetry: The Twentieth Century (2000). His many honors and awards include the 2014 Ruth Lilly Poetry Prize and the 2015 Bollingen Prize. From 2001 to 2007, he served as a chancellor of the Academy of American Poets. Mackey taught for many years at the University of California, Santa Cruz and is currently the Reynolds Price Professor of Creative Writing at Duke University.

Nathaniel Mackey was born in Miami, Florida, in 1947. He earned his BA from Princeton University and his PhD from Stanford University, and is the author of numerous books of poetry, including the National Book Award-winning Splay Anthem (2006) and Eroding Witness (1985), which was chosen for the National Poetry Series. He has also published several book-length installments of his ongoing prose work, From a Broken Bottle Traces of Perfume Still Emanate, which critic David Hajdu described as “not simply writing about jazz, but writing as jazz.” Mackey cites poets William Carlos Williams and Amiri Baraka, in addition to jazz musicians John Coltrane and Don Cherry, as early influences in his exploration of how language can be infused and informed by music. Also known for his editorial work and critical bent, Mackey has coedited the anthologies Moment’s Notice (1993) and American Poetry: The Twentieth Century (2000). His many honors and awards include the 2014 Ruth Lilly Poetry Prize and the 2015 Bollingen Prize. From 2001 to 2007, he served as a chancellor of the Academy of American Poets. Mackey taught for many years at the University of California, Santa Cruz and is currently the Reynolds Price Professor of Creative Writing at Duke University. Joseph Donahue is the author of several poetry collections including Wind Maps I-VII (Talisman House, 2019) and Red Flash on a Black Field (Black Square Editions, 2015), as well as several works which are sections of his ongoing long poem Terra Lucida. He lives in Durham, NC and is Professor of the Practice of English at Duke University.

Joseph Donahue is the author of several poetry collections including Wind Maps I-VII (Talisman House, 2019) and Red Flash on a Black Field (Black Square Editions, 2015), as well as several works which are sections of his ongoing long poem Terra Lucida. He lives in Durham, NC and is Professor of the Practice of English at Duke University.