by Joyelle McSweeney

photo by Beverly Brathwaite

Born in Barbados in 1930, Kamau Brathwaite has contributed a lifetime of effort to the peoples, cultures, literatures, and languages of the Caribbean and the world at large. A poet, scholar, linguist, and cultural theorist, he took his bachelor’s degree with honors from Cambridge in 1953 and, after stints as a public servant and teacher in Ghana and Jamaica, earned a PhD from Sussex in 1968. He has since taught at the world’s top universities and authored upwards of sixty books of poetry, prose, literary criticism, drama, cultural studies, autobiography, and history. A member of the board of directors of Unesco's History of Mankind project, he’s also served as cultural advisor to the government of Barbados, and his prizes, including a Guggenheim and Fulbright, are too numerous to list here.

Brathwaite’s tireless output and status as a public man of letters recall Yeats, as does his interest in the spiritual and ancestral forces that animate landscape, nation, and history. Yet Brathwaite’s stylistic and formal innovations have been equally tireless. As his career has progressed, he has invited more and more vernacular energies (namely a distinctively Caribbean English, Nation language) into his poems, and by the 1980s was breaking away from normative poetic conventions of typography, layout, and appearance, using a dot-matrix-style printer to create a more democratic, expressive visual effect, a kind of visual vernacular. He refers to this style of visual presentation as "Sycorax video style," after the mother of Caliban in The Tempest, the witch Sycorax whose magic Prospero has stolen, along with the island. 2001 saw the re-publication of the important trilogy Ancestors reset in Sycorax video style.

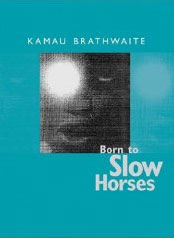

Brathwaite’s new book, Born to Slow Horses (Wesleyan University Press), represents a redoubling of all these energies. It’s a composite text, including prophesy and anecdote, drum songs and jazz riffs, unconventional forms working personal, national, and international events into the mother matter of history and memory. The book also recounts a visionary incident in which the specter of an ancestral slave woman, called Namsetoura, appeared to Brathwaite at his home in CowPastor, Barbados. An angry Namsetoura revealed the spot to be a sacred gravesite and charged Brathwaite not to leave his land, which had been expropriated by the government of Barbados for an airport road. This life-changing visitation has recharged Brathwaite’s style and sense of purpose and also locked him in a battle with his government which is stretching towards its tenth year.

In the following interview, conducted on September 14, 2005, Brathwaite and I discuss Hurricane Katrina, the battle for CowPastor, the visitation of Namsetoura, and Brathwaite’s charged and evolving relationship with style and poetry, ecology and technology, nature and history.

Joyelle McSweeney: We’ve recently experienced such a catastrophe on our Gulf Coast, I’m sure you heard all about how terrible it was.

Kamau Brathwaite: Of course, of course.

JM: —and we also just had an anniversary of 9/11. Catastrophe is an interesting thing for American poets; a lot of people seem to shy away from writing about public themes or very recent things, maybe because they don’t know how to handle them in their writing. But you’re a poet who writes from catastrophe, in that you write about the Middle Passage as almost a constant condition. I wonder what you have to say about writing from catastrophe and how art can come out of catastrophe.

KB: Art must come out of catastrophe. My position on catastrophe, as you say, is, I’m so conscious of the enormity of slavery and the Middle Passage and I see that as an ongoing catastrophe. So whatever happens in the world after that, like tsunamis in the Far East and India and Indonesia, and 9/11, and now New Orleans, to me these are all aspects of that same original explosion, which I constantly try to understand. What is it that causes nature to lunge in this cataclysmic way, and what kind of message, as I suspect it is, what message is nature trying to send to us? And how are they connected, these violent forces that hit the world so very often— manmade or nature-made or spirit-made—they hit us increasingly violently. And I’m at the center of this, I feel—what I have experienced here at CowPastor is a miniscule version of the same thing. That one should have found a home, after a long period of peregrination, and within minutes of finding that home, to be told that you have to leave, on a flimsy, unethical excuse, is another form of catastrophe.

JM: Yes, I agree. In fact, I’ve been thinking about the ways in which things, which we at first glance think of as natural disasters, always have this manmade component—whether it’s causing or whether it comes after this natural disaster, and it’s getting harder and harder for me to see the line between manmade and natural disasters.

KB: You begin to feel that New Orleans, I suppose, is one of our tragic examples, where nature constructed the basin below sea-level, and man came there, built upon it, and constructed his and her theories and hopes and dreams in basically such a fundamentally corrupt way, that when the pressure really hit, the dikes and the levees and the theories have altogether collapsed under the pressure and promptings of nature. And New Orleans for me is an example of how Nature uses so much of man’s doings to send a new message.

One thing about catastrophe, for me, is that it always seems to lead to a kind of magical realism. That moment of utter disaster, the very moment when it seems almost hopeless, too difficult to proceed, you begin to glimpse a kind of radiance on the other end of the maelstrom.

JM: Another way in which nature rises up to intervene is the sort of experience you’ve had with—I don’t know if I’m pronouncing this right—Namsetoura?

KB: Yes. Namsetoura. ‘Nam’ is a concept of mind which is the opposite of man’s mind, ‘man’ spelt backwards, and ‘nam’ also means an imperishable spirit; so ‘man’ is a distortion of ‘nam’. And Namse is a version of Anansi the Spider. So the spider is part of the ‘Nam’ and the ‘Nam’ is a part of the Spider. And ‘toura’ is a way of telling stories.

JM: I see! So when you saw her in your garden, do you feel that that was another kind of intervention?

KB: Of course, that was a presage to what was going to happen because nothing had happened yet. What had happened was that when I was told that I would have to leave CowPastor, I began to photograph everything I could on the pasture, and the pasture itself is about two miles long, and my little area, which is on a ridge between the sea and the hill, is only two acres. And I decided that I would try to photograph everything I could as a kind of memory bank for what I assumed I was going to leave. And on this afternoon when the sun was at two o’clock, three o’clock, when my wife and I were in this little clump of bush which was just behind the house, what you call the garden, and the sun suddenly illuminated this magnificent spider’s web, with a spider at the very center of it. So naturally I went to photograph it. I could see the spider perfectly clearly through my naked eye, but as soon as I looked through the view finder of the lens there was no spider, there was no web, there was nothing! And this happened, of course, two or three times. Each time I went to take the picture there was no evidence of reality. So finally I decided to take the picture anyway. And as soon as I did that the lens split right across its equator.

JM: That’s amazing!

KB: I know, right. So I changed the lens, and got a different lens, and then I did the same thing, and this particular lens almost melted in my hands, got very hot, in fact it burned my fingers as well. So then I felt quite desperate because this seemed to me an extraordinary phenomenon. So my wife went to fetch her box camera, just determined to take this picture. And she clicked the spider, twice. And that was it. We couldn’t see if she got the picture but at least she clicked, and nothing more had happened.

When we took the Kodak to the guy who processed the film, what came out was two, three, actually four pictures came out that afternoon. One spider, normal looking, in the web, the second one, still reasonable, in the web, the third spider seemed to be receding from our gaze, and the fourth shot came up was the image of Namsetoura.

JM: And that’s the image on the front of your new book?

KB: Right. And you can imagine how one felt.

JM: (laughs) No, I cannot! How did you feel?

KB: What happened immediately, I felt compelled to begin to write from this experience. I started out trying to get a narrative, but as I began to conceive of a narrative, this image began to talk to me. Now this is where things get really dizzying. So that the poem that is in the book you are holding is in effect not only my description of what happened, but the words Namsetoura begins to speak to me. And what she tells me is two things: first of all, she’s been here for three hundred years, and no one has ever thought of looking for her, no one has ever thought of a burial, no one has ever thought of respect, so her soul is in a kind of limbo or perturbation. And, secondly, that here I am now to disturb her peace, on the grounds that I am a Caribbean, Barbadian poet, but that as far as she’s concerned, I’m like all the other people through the last three hundred years, don’t know a damn about her, about her condition—her life here on the plantation as a woman, her life as an uprooted African princess or priestess or whatever she was. So that she criticized my own sense of poetry, which is a very humbling experience. She did it in a way which was quite unexpected because normally one would expect a sybil to speak in an oratorical manner, in a very correct, abstract system. But instead of that she used very salty language. She spoke in a mixture of Asante Twi, Ga, and Barbadian Nation language. But she spoke in a very—not a hostile manner—but she used a lot of four letter words. I mean, she chewed me out properly. And that was also, as you can imagine, quite humbling. And the third thing she did was, she implied that if want to really write a poem, having discovered her burial ground, and that if I was to be a man, she said, using ‘man’ in a very sexual manner—if I was to be a man, I would have to have the balls to be able to defend her pasture. That was her indictment to me, her declaration to me that afternoon. And it so happens that soon after that I began to think no longer of leaving CowPastor as we’d intended to do, but I decided, why not stay here and try to defend the situation. I mean first of all I was going to defend her graveyard, I was going to have to challenge the archeologists of Barbados and the Caribbean to come and do some digging. To see what’s there, because you know, let us say that a million slaves died in this little island alone from 1650 to 1838. Let us say that, though we don’t know the exact number. But do you know from all those people dead, after all that time, Barbados claimed they’ve only one graveyard on this whole island.

JM: I don’t believe it.

KB: Yes, it’s unbelievable. I mean, that hit me for the first time, too. But the graveyard that has been discovered by archaeologists from Harvard University happens to be just over the hill from CowPastor. So again, the sense of connection begins to make itself felt.

But what she said is that I should do some real research, I should defend her sacred space, and I should become concerned therefore with the environment, both historically and spiritually, from which she had come. And soon after that I began to make it clear to the government of Barbados, without much response, that I was not going to leave CowPastor until I got some clear explanation as to why they wanted to build a road through this place.

JM: Right.

KB: The road is not necessary here, there are two good roads on either side of the pasture, and my position is that it seems as if all they wanted to do is to build a road because a road can be built. There’s space here, there’s green here, there’s lovely ground here, so why not build a road which makes it easier to get to from the airport to the next village.

JM: So where are you in this?

KB: After I declared that I am not leaving until there was some kind of public discussion of why this is deemed to be necessary, I got no reply, I never got a reply yet from any authority. And that was ten years ago. I’ve been fighting this thing since 1997. I saw Namsetoura just on the cusp of 2000.

And this is a beautiful place with cows grazing and a very peculiar brand of goat we have in Barbados which we call a black-belly sheep, a goat unique to the island, you know, it’s a place I call a Serengeti, a place for grazing and rumination and the rhythm of the animals, people coming to collect the cows in the evening and so on. But, the government decided that this entire pasture should be cleared and therefore the people who owned those cows, they are all now removed, those people have been cashiered off the space and therefore the cows have gone. And then from January this year until March there is a sudden violent outbreak of digging on the pasture, something which we could not understand. We woke up one morning to a clanking. They weren’t content to evict the people, they started digging everything up.

And then, on top of that, we have a very peculiar feature here which I called the Lake of Thorns. It is like a gulley, what you’d call a pond. A little lake, but it is dry in the dry season, but it is filled with water in the wet season. And that water comes off the surrounding highlands, and it helps to drain the pasture. That’s one thing I did get, an undertaking from the authorities, that they should not destroy this pond as well. Because it’s a very unique feature, it includes mangroves, and all sorts of little shrubs and plants in there which I don’t think our botanists have really got to yet. All sorts of little animals, even the monkeys come migrating through here. So it was a unique little special wing of nature.

Well, in all this digging and thumping and clunking, they filled in that pond as well. That’s when I went on the Internet. Because I couldn’t get any satisfaction with the local authorities. I decided at least to talk to the rest of the world about these things. And I got a fantastic response. I never knew the Internet was such a remarkable medium.

JM: Interesting…

KB: Yeah, lots of people are responding, and of course people pass the word from one to the other, and a guy came forward from Cambridge University, who is a poet—

JM: Right, Tom Raworth.

KB: Tom Raworth, right, do you know him? He decided to anchor the whole thing on his website and that made a big difference.

So anyway, as a result of that campaign on the Internet, somebody whispered to somebody who whispered to somebody and there’s now a token little ditch which is supposed to represent the return of the Lake of Thorns.

JM: (laughing) Oh no.

KB: That was the only kind of response we’ve had.

JM: Well, this interview will be on the Internet and I imagine a lot of people will read it. What response do you want from people who read about your case and care about your poetry? What can people do?

KB: That’s the trouble. There’s nothing really that people can do. But if only… Let us say that one day George Bush’s wife might see the site—I’m just giving a fantastic example—and that she became so moved that she decided to speak to the President of Barbados and ask him what’s happening. All that I can hope is that the wider this thing spreads and the more people get to know that the greater the chances that someone of real influence might be able to intervene. Because it seems to me that poets and well-wishers and journalists and literary critics are quite ineffective (laughs) for what I’m up against here.

It is a horrible story, but what is even worse is that with the digging up of the pasture, now it is no longer Serengeti. Apart from the little spot that I defend, the pasture itself is now a hostile environment because the grass is gone, the cows which used to graze the grass are gone, and the place is now an overgrown wilderness. And now it is beginning to encourage vandalism because people are now coming out to the pasture and taking away blocks of stones from some of the houses that were destroyed and so on. It is no longer the kind of place that one would instinctively recognize as a place where psalms could be written. It is no longer a question of David; it is more becoming something like John the Baptist.

JM: Well, how do you take that? Do you think you have an imperative to stay and be John the Baptist here? What do you think is next for you? How long do you think you are going to stay?

KB: I really have no idea. You see, there’s still Namsetoura. I get the impression from my communication with her, and it has been very difficult and I really can hardly hear her, but my impression is that unless there is some kind of rational discussion between myself and the government, then I will stay where I am.

But the whole thing about it is that I’m learning so much about poetry. The pasture is teaching me poetry, because what one would defend about the pasture when it is beautiful, it is harder to defend when it’s ugly. If I came here when the place was utterly hell, I would have left like anybody else. In a sense now, I am faced with a nostalgic situation, perhaps. I’m now harking back after Eden or harking back after a Lost Paradise, something like that.

JM: In what way do you think you’re learning about poetry from the pasture? Are you being taught a dedication or being tutored in nostalgia?

KB: Nostalgia, yes, I can say that quite frankly because the pasture teaches me so much—or I could say Namsetoura, the pasture and Namsetoura, because the two things are so closely connected, the pasture and this image. I can say I’m having a nostalgic phase, I tell you confidently without any embarrassment. I can say this perfectly clear, I don’t feel in any way defensive about it. Nostalgia now begins to have another meaning. Nostalgia means that there is some vision which it is important that we try to preserve. It goes beyond just fact, into something entirely different. It has become standard which you now try to uphold, it is a standard which you try to teach people about, which you hope that others begin to recognize.

In other words, Barbados as an island itself. It was such a beautiful place, not only CowPastor, I’m just a small example, but the entire island is being overrun by building, you know, there’s hardly any grass left. We don’t feed ourselves anymore. We import everything—all our food, all our fuel, everything—and we’re selling large chunks of land to wealthy foreigners, as well…

For the native poet like myself, that is where the nostalgia comes from. All the places where my poetry came from have been taken over by hotels. And they now squat upon my metaphors.

JM: I see.

KB: And not only on my metaphors, but I’m in pretty close contact with the younger poets on the island, and the scope of their vision is increasingly narrow. Their sense of history was never very clear, but their sense of nature, their sense of environment, their sense of possession of space is being slowly dwindled, into, you know, a tenement yard or a space of concrete where you might play baseball. Rather than the great game of cricket which we were famous for.

JM: Right.

KB: And it seems to me that if they’re not careful, instead of poetry, the outward celebration of life which you communicate to others, that poetry can then be poured into drugs, and you can get into a situation that is quite well known in the cities, where the outlet, in the long run, becomes that needle. Or that little spliff. Because you see you can no longer see the sky and feel the breeze and if you do have some creative urge, if you do have a sense of inspiration, to use those grand words, you might find yourself slowly crawling into your own viscera rather than having anyone to share it with.

Right now in CowPastor I no longer can share my outward poetry with the people in Thyme Bottom, who have the cows. So, even as I speak to you, I speak to you almost out of a tin box here in CowPastor rather than speaking to you with a sense of community around.

JM: Well, this is a very devastating story. But another thread that I hear is, and it links to the Sycorax video style, is about technology. You went onto the Internet and you discovered the scope that it has, and the kind of connection it can make. It seems to me that that’s something that runs through your work—both its animistic interest in ancestors and spirits on that level, and an interest in technology, in manmade technology. That doesn’t seem to be in conflict for you—the two seem to go together. Do you think that’s the case?

KB: In fact you are the first person who’s mentioned this, that you notice that the CowPastor and the Sycorax style might all be connected. I really hadn’t realized that, and I really cannot tell you precisely where that link is. The Sycorax actually begins from 1980 when I had those several catastrophes in my own life. You know, the death of my wife, the destruction of my oumfo, and then my death at the hands of the three horsemen of the Apocalypse. [Brathwaite here refers to a traumatic break-in in which a thief placed a gun to the base of Brathwaite’s skull and pulled the trigger. No material bullet was fired, but Brathwaite feels that a ghost bullet traveled through his skull at that moment and rendered him "dead." His life since then is of a different category than his life before.]

JM: Right.

KB: Those three incidents were so traumatic that I was not able to write anymore using my hand as I used to do. And I became a kind of granite. My fist was like stone. And that’s when I came across my first wife’s computer and I began to play with it and discovered Sycorax lurking in the corner of the screen and that’s how the whole thing started. So the technology started from an earlier catastrophe. And it really doesn’t have a narrative connection with CowPastor. The technology, however, let us hope, might be able to sustain me through this second period of bleakness.

But, I’m sorry, it is not really bleakness. What I’m really looking at is a form of radiance. The bleakness is there because there is clearly no obvious end in sight. But I feel so elated at being here and discovering that—but it is not really technology, Joyelle, but an increasing link between myself and ecology, not technology.

JM: Oh, I see.

KB: I do not know where Sycorax video style fits in at all but what has happened to me is that I’m blessed here on this pasture by getting to understand nature in a way which I did not understand much at all. In other words, I used to understand nature via the English Romantic poets—you know, “I wandered lonely as a cloud.”

JM: Sure.

KB: And now I begin learning the details of a banyan tree that’s just here on the side of my house. And a certain tree that are called dunks trees that bear a very bittersweet fruit. And this dunks tree has its own choreography which one would not normally understand. When it begins to bear fruit the tree bends toward the earth. And the dunks, form a kind of stooping ziggurat, like a circular stair, make it easier to pick the dunks from the tree. And if the dunks are removed from the tree, ending that phase of its fertility, the branches begin to elevate once more into their position parallel to the earth. Little things like that, you know, the movement of trees, the kinds of birds and how they build their nests, I have time here. I have time and no rush to get to know things.

JM: I see.

KB: Let me tell you how one time, there was a tree outside of my bedroom window which was trying to make me into a tree. I haven’t found words for it, but I began to understand that trees communicate, as they would have to do, and they found a way of communicating with me via hay fever.

JM: Via hay fever!

KB: What I thought was hay fever was whatever it was that they were using, that dust, as a kind of challenge toward my sensibility. And I’d never had an experience like that! But I went to see the guy who deals with allergies, he almost sent me to the lunatic asylum. When I started to describe what the trees were doing to my imagination, to my nerves, or how I was hearing the sound of growth, I mean, he really thought that I was not quite "in the locker."

JM: To me it feels like poetry has become a 360 degree experience for you, it’s coming through your body, it’s all around you. When I read the 9/11 poem in your new book, I was very moved by it as a linear piece of writing, but then when I read the note at the end about how you conceived of it as either a live performance or almost an installation piece, I was moved again, to consider it in 360 degree space. Does that make sense?

KB: Yes it does make sense. In fact, in the final version of that poem, it is in 360 degree space as you were quite right to say. It was performed here in Barbados to a soundtrack of Coleman Hawkins’ “Body and Soul,” and I used some video from the 9/11 disaster, and I had children’s voices, and the collapsing of the towers, things like that.

JM: So it’s not just a linear poem.

KB: Right, right.

JM: As terrible as the CowPastor incident is turning out to be, it excites me to think about you going onto the Internet and exploring its spatial—you write directly onto a screen and others will see it on a screen. It excites me to think where you might go next with technology and the ecological experiences you’re having.

KB: That’s very interesting. You of course instinctively recognize the power of the Internet. I think you’re a bit surprised that I took so long to recognize it. Really it was thanks to Tom Raworth that I realized what could happen there.

JM: Well, I read, in one of your conversations in the Nate Mackey book [read the Rain Taxi review here], that you have thought about making a poem with a video camera. That’s what made me have this train of thought.

KB: I got a video camera, but I haven’t yet got there.

JM: Well, given your experiences with the regular camera and Namsetoura, I’d be a little nervous, too.

KB: I don’t think I would get that kind of confrontation again. I think that was such a remarkable experience, that, were it to happen to me again, I think I would really be a bit alarmed. Like something had "gone wrong with the wiring." I see Namsetoura as a unique experience. Because the things that she said… For instance, I call my wife Chad, and right away this woman referred to Lake Chad, in central Africa, you know. Her images of water began to make me recognize that she was very much aware, as she should be, of the Lake of Thorns. Though when she was speaking the lake was dry. But as soon as they began to fill that pond in, I knew that what she’d said about water was an important admonition, in her transcript to me. So water becomes an important element.

JM: Yes. It seems like it’s always been important. Through all your different books and styles, that water image is there.

KB: Yes. And then of course New Orleans now begins to haunt me in an entirely different way from 9/11.

JM: Right. I thought of that as well. A way that you have conceived of tide and tidelectics and almost taken that ocean of the Middle Passage and turned it into a cognitive space, a space in which perhaps Caribbean peoples can think outside the Western mode of the dialectic. A kind of tide which touches things. And as I was having this thought, I was really struck by this amazing tide in New Orleans. It does seem connected.

KB: Right, and of course New Orleans is part of the Caribbean.

JM: And part of the story of the Middle Passage.

KB: Right, it is one of the rich deposits of the Middle Passage. There has always been vital connection between the Atlantic Middle Passage and the Mississippi.

JM: Yes.

KB: And if you draw a line from the Mississippi into the Caribbean, you reach the island of Guadalupe. And if you draw a line from the Niger from West Africa across the Atlantic you reach the island of Guadalupe. And the island of Guadalupe is in the shape of a butterfly.

JM: The imagery is there, written on the Earth.

KB: Yes!

JM: I have one last question for you. Several times, now, unfortunately, you’ve been in a struggle to find a secure place for your archives. And in this new book, you have so many forms in it: elegies, of course, and drum songs, and newspaper clippings and letters, anecdotes, essays. It seems like the archive itself is almost becoming a poetic form for you.

KB: I hadn’t thought of that. I suppose the only way to keep the archive is to write a poem!

JM: I see it happening in these books and it makes me optimistic.

KB: And then CowPastor becomes a poem too.

JM: I see that! I can see it from Alabama!

KB: Oh you are speaking from Alabama. I was thinking of you in New York. So of course you are dealing with Katrina. You must be feeling the vibrations of that.

JM: Yes sir, it’s very much a part of even our sense of space, to know that this terrible thing is happening so close. But also, it’s been our privilege to take in people who are evacuees. It’s been a very dark time, and I don’t know how it’s going to… I don’t know how it ever could resolve.

KB: I always say that the one factor you can never take out, is the human one. And what human beings can do in New Orleans, now, we have no idea, but I get a sense that they are going to miracle-ize that place all over again.

JM: Oh, I hope you’re right. I hope you’re right.

Click here to purchase Born to Slow Horses at your local independent bookstore

Rain Taxi Online Edition, Fall 2005 | © Rain Taxi, Inc. 2005

Siddhartha Deb

Siddhartha Deb