Edited by Edward Foster and Joseph Donahue

Edited by Edward Foster and Joseph Donahue

Talisman House ($25.95)

by Chris McCreary

In The World in Time and Space, Alan Golding's closing essay "New, Newer, and Newest American Poetries" surveys the numerous major anthologies of 20th-century innovative writing that all position themselves, in one way or another, as the true heir to Donald Allen's seminal The New American Poetry. Expanding on an argument by Marjorie Perloff, Golding astutely notes that these anthologies are often focused on "historicizing" their poetic projects and reinforcing established careers instead of introducing rising writers as was the case with the Allen anthology. Timing, it seems, is of the essence when documenting the ever-evolving history of contemporary poetry.

It's of no small significance that "time" appears twice within this volume's full title. While The World in Time and Space, presented as issues 23 through 26 of the journal Talisman, is often retrospective in its focus, it does not dwell on the past; instead, it is about the threads connecting the various schools and stances to be found within the last 50 years of experimental poetry, including that which is being written today. The volume's editors are wise to begin their subtitle "Towards a History"—in no way do they claim that this volume of reviews, interviews, and essays is comprehensive, despite its 740 pages. The version of history that is put forth here is particular to the aesthetic that Talisman House has been so impressively mapping for well over a decade. It is a family tree that certainly shares members with other existing histories, but the emphasis is redirected, and those who are generally considered secondary figures stand in the spotlight.

William Bronk emerges, not surprisingly, as the anthology's most central figure. Talisman House has published more than half a dozen collections of the prolific poet's work, and The World in Time and Space is dedicated in his memory (Bronk passed away in 1999); the volume's title is pulled from one of his poems, which appears here as well. Aside from being the focal point of David Clippinger's "Poetry and Philosophy at Once: Encounters between William Bronk and Postmodern Poetry," Bronk appears, at least briefly, in several other pieces. He emerges as a crucial influence who was at the same time an "anomaly," sharing an affinity with several schools of poetry yet not fitting neatly within any of their confines. Tracing Bronk's influence, Clippinger links his philosophical poetics to the work of writers such as Susan Howe, Michael Palmer, and Rosmarie Waldrop. Elsewhere, Peter O'Leary includes Bronk in his innovative take on the gnostic tradition, which he also expands to encompass poets such as Howe, Nathaniel Mackey, and Robert Duncan as well as Ronald Johnson and Frank Samperi, two poets who figure somewhat less prominently but still crucially in the canon put forth by this collection. Leonard Schwartz's essay on Duncan, then, traces his lineage through Palmer, Mackey, and younger poets such as Eleni Sikelianos. As the essays progress, the overlapping of these circles becomes even more apparent.

Around this nexus, then, other essays and reviews provide broader surveys of poetic strains ranging from the Objectivists and Language poets to slam poetry and visual writing. While much of the focus is on poets who emerged in the 1970s, the poetic trajectory at times includes more recent generations as well. In "Neo-Surrealism; or, The Sun at Night," Andrew Joron tracks surrealist tendencies in poets such as Philip Lamantia, one-time youthful protégé of the original Surrealist circle, through John Yau and up to younger poets such as Kristin Prevallet, Jeff Clark, Brian Lucas, and Garrett Caples. Steve Evans targets the late 1980s as the beginnings of a reworking of avant-garde practices by a new grouping of poets that truly came into their own by the middle of the 1990s. He focuses discussion on a cluster of six younger poets—Kevin Davies, Lisa Jarnot, Bill Luoma, Rod Smith, Lee Ann Brown, Jennifer Moxley—that form a loosely-knit confederacy despite their lack of manifestos or an official "school."

It must be pointed out that in the version of history presented by this collection, women are something of a minority. A tally of the contributors list reveals that only a quarter of the volume's contributors are women. The inclusion of an essay by Perloff is a given—at this point, no collection of work on contemporary poetry would seem complete without one—and an interview with Alice Notley further reaffirms her importance within both the Talisman House stable of favorite writers and contemporary poetry in general. And while Howe is frequently a focal point, there are some other women whose work would seem to deserve closer analysis. Anne Waldman, for instance, is credited in this volume's Introduction with ascribing the term "outriders" to innovative American poets, and she appears briefly as a historical figure in several of the pieces collected here, but no essay or review gives in-depth consideration to her writing. It seems ironic, then, that Mary Margaret Sloan writes in "Of Experience and Experiment: Women's Innovative Writing 1965-1995" that in recent decades "avant-garde anthologies have gradually included more and more women until in the 1990s, many collections represent women's work in nearly equal quantities as men's, and in a few cases, the works of even slightly more women than men." In the context of this essay, it is difficult not to see the contributors list of The World in Time and Space as something of a throwback to an earlier, more male-dominated time. Sloan's essay gives attention to many of the essential women writers who are neglected elsewhere in the collection, but the piece is stretched to its limits, eventually resorting to lists of female poets' names when at least some of these poets deserve fuller consideration in a volume of this anthology's size and scope.

While the disproportionate number of men contributing to the anthology is too striking to ignore, by no means should this collection have attempted to be all things to all readers. In his introduction to the Angel Hair Anthology, itself an impressively large collection that pulls together work from Waldman and Lewis Warsh's groundbreaking 1960s small press, Warsh writes that "(w)riting poetry criticism during the late sixties was to associate oneself with an academic world, and a tone of voice, which was considered inimical to the life of poetry itself." A sea change has obviously occurred in the world of experimental poetry since those days; today, many poet-scholars publish critical work alongside more traditional members of academia. Numerous journals are dedicated entirely to poetics, and high-profile presses such as the University of Alabama Press and Wesleyan University Press regularly publish a wide variety of critical writing on poetry. With such a wealth of poetry anthologies and critical work already in print, surely part of the editor's job today is to decide what constraints to place on a project so that it is somehow differentiated from the other volumes already on the shelves. When editing The Art of Practice: 45 Contemporary Poets, for instance, Dennis Barone and Peter Ganick limited the anthology's range by deliberately choosing poets whose work had not been included in the earlier anthologies In The American Tree or "Language" Poetries. Thankfully, too, volumes such as American Women Poets in the 21st Century: Where Lyric Meets Language, edited by Claudia Rankine and Juliana Spahr, and We Who Love to Be Astonished: Experimental Women's Writing and Performance Poetics, edited by Laura Hinton and Cynthia Hogue, provide some necessary consideration of today's innovative women writers.

While some of what's included in The World in Time and Space has already been said elsewhere in more depth and some key figures are left out, what emerges is the aesthetic of Talisman House, one of the most vital publishing projects of the 20th century and beyond. The project is admirable, even if it inevitably leaves stones unturned. One can only assume that there are other editors currently preparing more volumes to round out the larger, more comprehensive history of the spaces to be found within contemporary poetry.

Click here to buy this book at Amazon.com

Rain Taxi Online Edition, Winter 2002/2003 | © Rain Taxi, Inc. 2002/2003

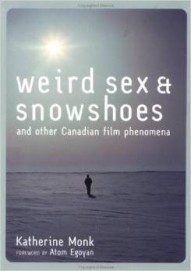

Katherine Monk

Katherine Monk