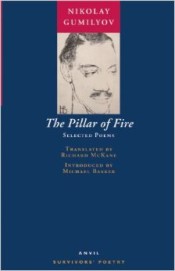

THE PILLAR OF FIRE

THE PILLAR OF FIRE

Selected Poems

Nikolay Gumilyov

translated by Richard McKane

introduced by Michael Basker

Anvil Press / Dufour Editions ($22)

SELECTED POEMS

Nikolay Zabolotsky

translated by Daniel Weissbort

Introduction and Essays by Robin Milner-Gulland and Nikita Zabolotsky

Carcanet Press ($25)

by Christopher Mattison

The Pillar of Fire—Richard McKane's translations of the early 20th-Century Russian poet Nikolay Gumilyov—is monumental in that it places a broad range of Gumilyov's poetry back into print in the English-speaking world. The collection contains selections from nine books spanning 1908 to 1923, including later uncollected poems, a generous introduction and notes by Michael Basker, and poems by Anna Akhmatova written for Gumilyov. As is detailed in Basker's introduction, Gumilyov spent much of his life nearing the point of internal combustion while traveling widely through Africa and other exotic ports of call. To some extent Gumilyov's poetic work has been overlooked due to the sheer brilliance of his contemporaries—most notably, his once wife Akhmatova; while the same fierce energy that led him through numerous tumultuous relationships and continents also helped to scar him, in the mind of some critics, as a figure ultimately more important as a source of inspiration than as a poet of primary importance.

Such a book should be the force necessary to reintroduce the world to a Russian poet of more than passing significance, but the book's broad range is ultimately one of its downfalls. Lauded for his previous translations of Akhmatova and Osip Mandelshtam, McKane does not truly hit his stride until the last full book of the collection, Gumilyov's The Pillar of Fire. Up to this point, the more elegantly translated stanzas are riddled with drafts that fail to resonate as anything more than solidly literal trots. McKane is precise, but he often fails to meet the ideal that he sets for himself in the translator's introduction, "to communicate the words of one poet of one country to the readers of the other country. The translator is like a pane of glass through which one can glimpse the heart of the matter . . ." McKane certainly does communicate from one language to the other, but this communication seems limited to the reproduction of words for words that only just begin to skirt the heart or its matter. His treatise is innocuous enough, but as translators slowly become more visible to the general reader, and readers subsequently become more familiar with translation issues, innocuous runs the risk of graduating to insidious. A myriad of issues could have been dealt with concerning the technical aspects of the formalist catches of rhyme and meter, an extended discussion of Gumilyov's place within Russian poetics, or even McKane's place within the small number of active and well known translators of Russian literature, but all these are swept aside for the same trite notions of translation and the heart.

In short, the majority of these translations could have benefited from some extended reflection and fewer lines of prose in verse form. Exceptions to this criticism are scattered throughout the book, such as in Chinese Poems: "In the deep cup there is still wine / and swallows' nests are on the dish"; or in Alien Sky, "I will go along the thudding sleepers"; but these individual lines lack the company to make the entire poem brilliant for an English reading audience. When I refer to the Russian originals, it is obvious that McKane is firmly entrenched in the basic meaning of the lines (in transmitting information), but it is impossible to read them without instantly wanting to substitute and invert.

To some extent it is necessary to refocus past the translations to the originals of Gumilyov, in that many of his earlier poems are considerably less mature, and thus not as interesting as the Gumilyov of the 1920s. McKane should also be given full marks for avoiding the abyss of mimicking Gumilyov's rhyme schemes. Even at those moments when the translations err on the side of literal attentiveness, they never degenerate into doggerel, which will inevitably make them a staple in the classroom, even if the collection does not win Gumilyov a broad new audience outside academia. At its core, this collection is scattered with graceful lines that occasionally reach the same level of intensity and personal longing that infested the mind of Gumilyov. What the collection lacks is the ability to consummate victory when the queen cries out in "Barbarians", "Nowhere will you find a wife more homeless / whose pitiful groans will be sweeter or more desired!" or else to rein in the "foaming steed" of translation and return home to the north. There was no place in Gumilyov's poetics for academic indecision or literal renderings. There was passion and travel and their offspring.

In contrast is Daniel Weissbort's translations of another Russian Nikolay—Nikolay Alekseyevich Zabolotsky (1903-1958). Divided into seven sections that cover the entirety of the author's poetic oeuvre, Weissbort assures the reader in his preface "that these are translations and not imitations, or my own poems." This is only partially true, in that Weissbort has transformed this Russian poet into his own, due in large part to the fact that he has been enmeshed in translating Zabolotsky for more than thirty years. Weissbort's understanding of the poet and the general worth of this collection are further expanded by the participation of Robin Milner-Gulland (a premier Zabolotsky scholar) and Zabolotsky's son, Nikita. On the surface, Milner-Gulland provides an introduction, notes, and a translation of Nikolay Zabolotsky's own account of his imprisonment in the Soviet camps, and Nikita adds an essay about his father that details more personal notes along with a timeline of the poet's literary history. Beneath this surface, their participation provides an image of the poet beyond the stanza—a point of particular importance due to the poet's relative obscurity up to the present day.

Nikolay Zabolotsky was a Russian Modernist and a founder of the OBERIU (Association of Real Art)—a group that bound together to defend "the various tendencies of leftist progressive or revolutionary art against those who sought to tame intellectual life and bring it under a single banner." Within the group's manifesto, Zabolotsky describes himself as "a poet of naked concrete figures, brought right up to the eye of the spectator. One should listen to him and read him more with the eyes and fingers than with the ears." This physicality and materialism is expressed before the poems even begin with Weissbort's discussion of approaching the poem "Agriculture Triumphant" alongside Joseph Brodsky. This elucidation of his own translation process simultaneously draws a map of Zabolotsky's devotion to "thingness," Brodsky's poetic mindscape, and Weissbort's synthesis of these various worlds. The translator's preface aside, each translation in this collection maintains an economy and intensity of language that swaggers between the absurd reality of 1920s Russia and the poetic gift of Zabolotsky—the ability to synthesize his chaotic revolutionary fervor with the natural world, as in "The School of Beetles": "We, carpenters, scholars of the forest, / mathematicians of the lives of trees . . . Rosewood teaches stone-breaking and house-building. / Ebony is metal's double, / a light for smiths, / for general and enlisted men an education." First time readers of Zabolotsky will notice a profound shift in his voice and themes after his release from prison, as he moves to more "harmonious" and classical Russian forms. Despite the considerably more subdued and melancholy tone throughout his post-imprisonment poems—"Long ago / A man bitter and wasted from hunger / Walked through a graveyard"—one is still able to make out the "consciousness still flickering" within Zabolotsky, in lines such as, "O, trees, recite Hesiodic hexameters, / be amazed by Ossian, mountain ash; / nature, it is not your long sword that sounds".

In general, I am more struck by his pre-imprisonment verse, but as this is meant to be a representative selection, the more melancholy post-imprisonment material also must be included. Unlike Mayakovksy and other poets who perished either by their own hands or at the hands of the state, Zabolotsky was able to defuse his politics and retain the revolutionary force that informed his earlier poems right up to the series of heart attacks that took his life.

This is an essential book not only for purveyors of Russian literature, or for those interested in the poetry of "survivors"—specifically of the Stalinist purges—but for anyone with fingers enough to reach into the "Monkish man who quits the stove / to climb into a bath or basin." The poetry of both Gumilyov and Zabolotsky should be grasped with these same fingers, as not only Russian, but world literature in general has been greatly transformed through their influence. The overarching difference between McKane's Gumilyov and Weissbort's Zabolotsky is that it's doubtful if McKane ever climbs into the bath. His reminiscences in the preface tell a romanticized tale of dabbling with the lines of Gumilyov on trains while translating Akhmatova and Mandelshtam. As McKane writes in the preface, "Gumilyov himself once said that he was a traveler, soldier and a poet in that order." With this collection, Gumilyov may be doomed to maintain that hierarchy. Nikita Zabolotsky, on the other hand, should feel safe in knowing that his father's English voice has received the attention it truly deserves. And that the blank space he found among the notes of his father's final written words:

1. Shepherds, animals, angels

has now been filled, in part, by Weissbort's English translations.

Click here to purchase The Pillar of Fire at your local independent bookstore

Rain Taxi Online Edition, Spring 2001 | © Rain Taxi, Inc. 2001