Mary Norris

Mary Norris

W. W. Norton & Company ($24.95)

“If you must order baby back ribs, try thinking of ‘baby’ as meaning ‘miniature’ instead of ‘wee creature.’ Or become a vegetarian.” Between You & Me is full of such good advice. You’d expect as much from a book that quotes approvingly from Edward N. Teall’s Meet Mr. Hyphen: “Good compounding is a manifestation of character.” Mary Norris, copyeditor for the New Yorker, takes her job seriously; as she says when defending the magazine’s strict comma policy, “Another publication would let you figure it out for yourself. And if that’s what you want, you can always read some other magazine.” Figure out what, for example? Without the commas in “Before Atwater died, of brain cancer, in 1991, he expressed regret . . ." we would have only our common sense to tell us how many times Atwater died. Grammar makes it clear that the cause and timing refer to a singular death. Think you can do without the clarification? Maybe you can. But Between You & Me teaches you to think like (should we say as?) a copyeditor. It offers a fun mix of anecdotes from Norris’s life at the copy desk; historical curiosities such as the U.S.’s underappreciated “apostrophe-eradication policy” and the fact that “editors of Webster’s Third saved eighty pages by cutting down on commas”; and practical instruction on usage. Whether or not you know the meanings of nominative and accusative, this is helpful: “‘who’ and ‘whom’ are standing in for a pronoun: ‘who’ stands in for ‘he, she, they, I, we’; ‘whom’ stands in for ‘him, her, them, me, us.’”

2015 Really Short Review. Return to Really Short Reviews

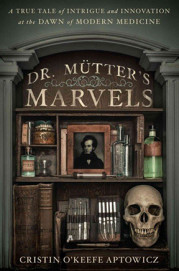

Cristin O’Keefe Aptowicz

Cristin O’Keefe Aptowicz