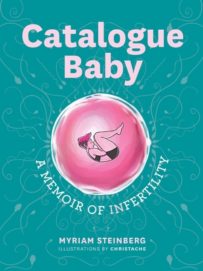

Myriam Steinberg

illustrated by Christache

Page Two ($24.95)

by Lisa Rizzo

Winner of a 2021 Vine Award for Canadian Jewish Literature, Catalogue Baby: A Memoir of Infertility tells the story of Myriam Steinberg’s quest to become a mother. Like many women today, Steinberg spent her early adulthood focused on her career; it was only as her fortieth birthday approached that she realized that if she wanted to have a child, she had better begin. She hoped her partner would join her in parenthood, but when that relationship ended, she decided to go it alone and found herself navigating the sometimes strange world of Trying To Conceive (or TTC, one of the many terms and acronyms Steinberg explains in the book’s glossary). She begins her journey with great optimism, but as her attempts fail, she finds herself enduring progressively more invasive procedures.

Steinberg pulls no punches when it comes to relating the details of her medical history. In her preface, she states, “There is so much silence around the pain that can accompany miscarriage and difficulties in conceiving. I hope this book will help de-stigmatize a terribly lonely experience.” Bravely taking the reader through every messy and heartbreaking moment, she structures Catalogue Baby in four sections, one for each year in her four-year saga. Some of the sections contain chapters titled with the name of a baby conceived but then miscarried; these parts of the book are heartbreaking to read, as Steinberg finds herself pregnant over and over, only to have her hopes repeatedly dashed.

It is with the depiction of this emotional rollercoaster that the graphic form of this memoir becomes important. While Steinberg’s narration helps orient the reader, and her simple, honest language effectively conveys the many angles of her experiences, Christache’s artwork, rendered in shades of maroon and black, propels the story via vivid images of raw emotion. The fusing of language and image allows the reader to linger, taking in the experience. One example of this is at the end of the chapter “Dahlia,” when an entire page is filled by one illustration: a black background with a grey figure huddled in a corner. A shimmer of pink floats up from her body. Steinberg’s only words: “I never did find out if I was right about the baby being a girl.”

Although Catalogue Baby is filled with such moments of anguish, Steinberg often uses humor to lighten the mood. This is another place the art plays a key role. One character in the book is Steinberg’s animated biological clock, which accompanies her to many of her appointments and sometimes seems to act as her conscience or her inner voice. There are also talking sperm and eggs, as well as dollar signs floating through the air when Steinberg pays for yet another expensive procedure. These subtly cartoon-like beings create imaginative respite for the reader (and perhaps the author herself), spaces to breathe before moving on.

This is a story of great determination, an epic journey filled with heartache and triumph; the author learns a great deal about herself along the way as she is forced to give up her fantasy of how she “should” become a mother. Steinberg describes both her medical procedures and her emotional state with utter honesty, while Christache’s illustrations often leave nothing to the imagination. While the author’s willingness to lay herself bare on the page may be startling at times, it affirms the need to confront the shame and secrecy that shroud this part of many women’s lives.

Those who have experienced infertility may find comfort in Steinberg’s commitment to breaking the silence about the emotional and physical toll this struggle can bring, yet this book can also serve as a lesson of hope for almost anyone dealing with difficulties in life. A story of courage and persistence, Catalogue Baby is a vibrant reminder of why so many people read memoirs: In learning about the specific lives of others, we might find shared emotional truths.