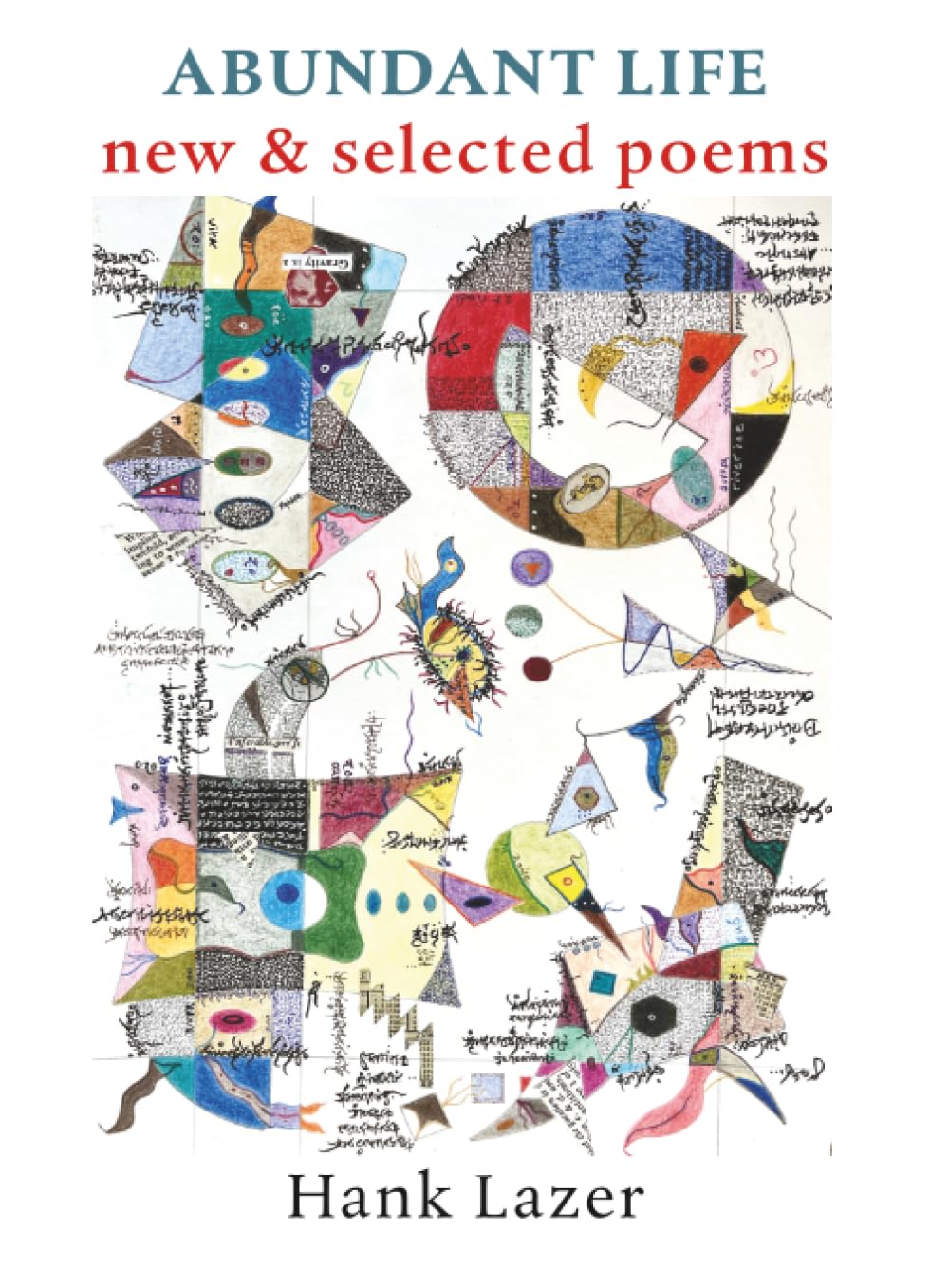

New and Selected Poems

Hank Lazer

Chax Press ($34)

A profound playfulness characterizes Hank Lazer’s Abundant Life: New and Selected Poems. Ranging from formal experiments to handwritten “shape” poems, the pieces here move from one revelation to another, but they are all grounded in everyday life and firmly rooted in Lazer’s improvisatory writing practices.

Lazer’s explorations of form are often delivered in “serial heuristics,” which the author describes in his Lyric & Spirit: Selected Essays 1996-2008 (Omnidawn, 2008) as “the developing of a particular procedure or form or set of rules for a series of poems which become . . . how I will live in poetry for that period.” The earliest collections from which Abundant Life selects contain such experiments. Days (Lavender Ink, 2002), for example, features ten-line poems that are dense with word play and seeming non-sequiturs. There is an off-beat, rhythmically knotty quality to these poems:

i sing the body

eclectic uh defective

icing the bawdy

directive rodin to young

rilke “toujours travailler”

all words & no fray

makes yack a dull

“stable & precarious”

Rose on licorice er

icarus’ wings

Lazer here plays with Whitman’s “I Sing the Body Electric” along with an instruction the sculptor Rodin gave to the poet Rilke—“work all the days”—which Lazer then uses as a springboard to riff on the saying “all work and no play makes Jack a dull boy,” rhyming “fray” for “play” and changing “work” to “words” and “Jack” to “yack.” He also suggests the hesitancy of improvisation with the quasi-words “uh” and “er” and bounces between allusions (there’s Icarus, of course, but also John Dewey and Gertrude Stein toward the end) in an offbeat, herky-jerky rhythm that mimics how thinking can come fitfully.

Abundant Life switches gears with one of Lazer’s most important poems, “Deathwatch for My Father,” from Elegies and Vacations (Salt Publishing, 2004). This is a long, diary poem with dated sections that pertain to Lazer’s experience on that day as his father was dying of leukemia. He begins by asking:

why am i

writing in the face of

your dying

Several pages later, after recounting his father’s gallows humor and their talk of golf, Lazer seems to have an answer, culled in part from poet George Oppen:

he would i know

encourage me (& perhaps has

in writing this poem) to

test poetry in the face

of the worst events

This is perhaps the most self-referential reflection in the poem, which insists on the dailiness of facing the anguish of a dying loved one. Lazer describes fighting tears as he goes golfing alone to honor his and his father’s love of the sport. Even amidst anguish, however, Lazer finds room for playfulness; in a kind of mid-line acrostic, he spells his father’s name:

not one prinCipally given to words

but works Hard these

lAst days

to wRite a series of thank you notes

the one to warren worries him a Lot

hE can’t get it right

with the noSe

Lazer turns to religion as a subject matter around 2005. Never devotional or dogmatic, he is interested in profound religious experience, not the institutions and their sometimes-numbing rituals. He describes himself as a Jewish Buddhist agnostic; in his recently published (and self-deprecatingly titled) What Were You Thinking: Essays 2006–2024 (Lavender Ink, 2025) he asserts that religious experience is “analogous to the reading experience of innovative poetry—an enigmatic encounter that requires patience, open-mindedness (in Zen terminology, the beginner’s mind), and the development of an ability (negative capability?) to live in uncertainty and with an ethical humility that suggests the incompleteness of our understandings.” For him, religious practice and innovative poetry both offer contemplative opportunities to keep the world fresh, open, and complicated.

In the 2010s Lazer developed a new form of writing: shape poems. This work is handwritten in cursive, with lines that roam freely about; sometimes the writing is even upside down, forcing the reader to rotate the page. These poems also include short quotations from philosophers Martin Heidegger, Emmanual Levinas, and Maurice Merleau-Ponty, and the last of this series of books, Slowly Becoming Awake (Dos Madres Press, 2019), integrates quotations from the 13th-century Zen Buddhist monk Eihei Dogen (e.g., “Do not treasure or belittle what is far away, but be intimate with it. Do not treasure or belittle what is near, but be intimate with it”). As with his other books that use quotation, Lazer chooses passages that are free from jargon and have meaning for readers unfamiliar with the thinker, and Slowly Becoming Awake uses about five different colors of ink, adding to its visual playfulness.

After his spate of shape poems, Lazer perhaps cheekily titled his next collection Poems That Look Just Like Poems (Presses universitaires de Rouen et du Havre, 2019). Sure enough, these are left-justified typewritten poems with short lines. The first of them, “As If,” reads:

i begin

each day

(which is already

a false statement)

attending to my

study & the yard

the bird feeders

the weather

certain that this

simplified world

exceeds my under

standing of it

With its immediate parenthetical disclaimer, “As If” gets at the rich complexity Lazer senses in “this / simplified world.” Immediacy is a value for Lazer; he tells us in What Were You Thinking that he rarely revises his poems, preferring them to be “of the moment,” and this momentariness consistently honors the specificity of the writing act as it occurred amid moods, attentional foci, obsessions, and sensible facts. For Lazer, everything is always different than it was. In its generalizing tendencies, language can give the lie to this abundance, but poetry can run counter to this tendency, reminding the writer and the reader of how specific, and precious, an individual moment is.

Lazer has continued his lean into life’s abundance in the current decade. In Covid 19 Sutras (Lavender Ink, 2020), he uses a variety of forms—centered four-line stanzas, serially indented four-line stanzas, long-lined free verse—to capture the grinding fear and dread during the pandemic, as in a poem about his elderly mother’s hospitalization:

i think

you are

on your way

& it pains methat i

that no one

can be

with you

In Pieces (BlazeVox, 2022), which lifts its title from a Robert Creeley book, Lazer pays homage to a “brown dog / actively sniffing / everywhere” and to a beloved uncle, a Biblical scholar who talked to God on his porch in the mornings, concluding that “anything seen / in an enlightened manner / becomes revelatory.” One could hardly put it more economically than that, but Lazer fleshes out his spiritual aesthetics in What Were You Thinking when he writes,

at the heart of spiritual experience is gratitude for consciousness, and some means of reflecting upon both that gratitude and the nature and possibilities of consciousness . . . If spiritual experience is in some way centered in the fact and experiencing of consciousness, no wonder then the intimacy of spiritual experience and language. And thus no wonder the intimacy and inter-dependency of spiritual experience and poetry.

For Lazer, poetry is akin to spiritual experience because both cause us to appreciate the countless particulars around us. Life is always more than we think it is, and Lazer’s entire poetic career has been reminding us of this plenty. An Abundant Life indeed.

Click below to purchase this book through Bookshop and support your local independent bookstore:

Rain Taxi Online Edition Winter 2026 | © Rain Taxi, Inc. 2026