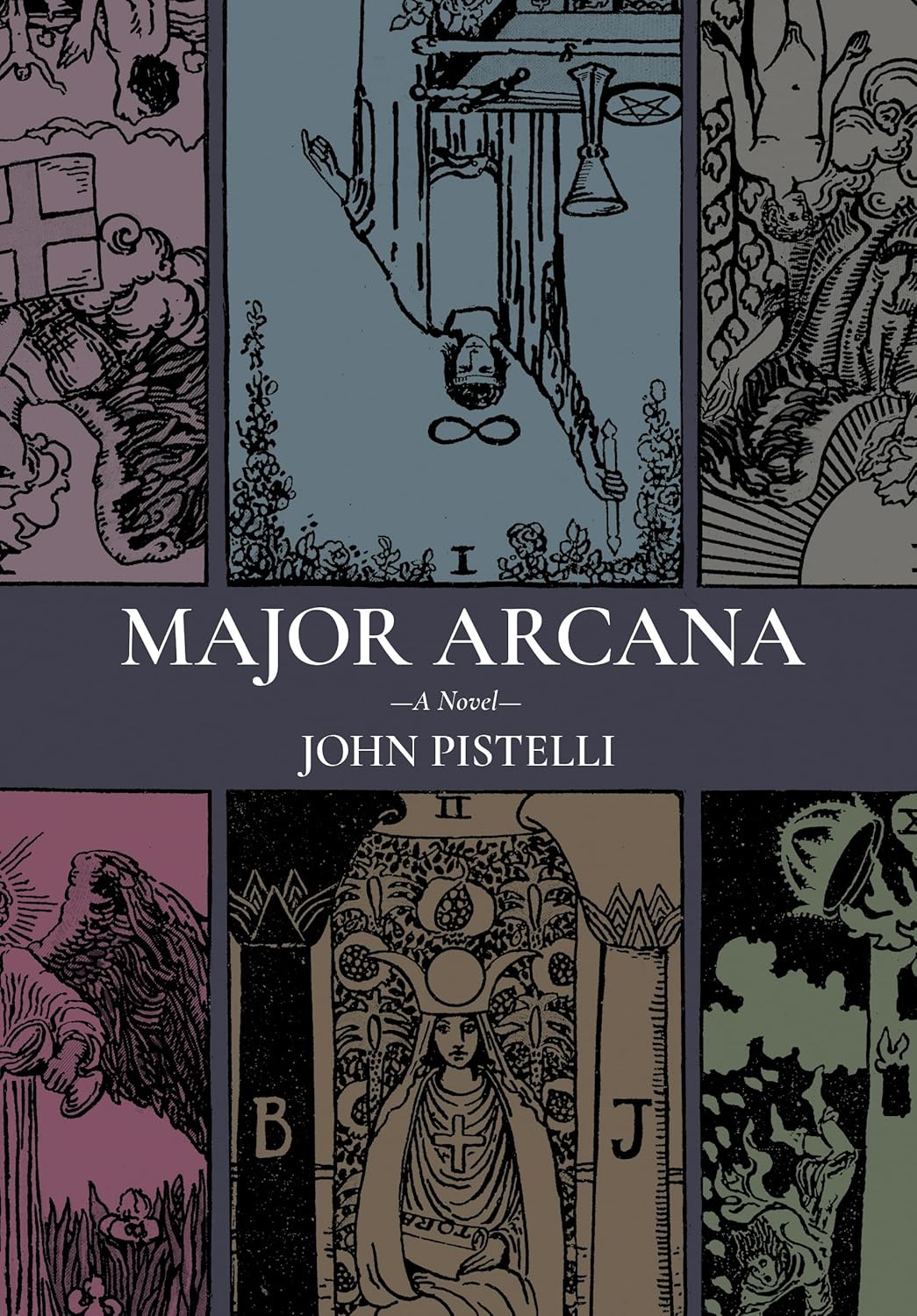

John Pistelli

Belt Publishing ($24.95)

It starts with a bang: A gunshot to the head, on a university campus, in Middle America, live-streamed. This action sets up Major Arcana as a story about “today,” the kind that would come with the tagline “ripped from the tabloids” if tabloids were still a thing. But as author John Pistelli plunges into the novel’s root question—why would an intelligent and seemingly happy college boy take his own life in such a public fashion?—its tendrils spread to encompass more characters, more mysteries, and more decades, until the story becomes a sort of secret history of the late 20th and early 21st centuries. “Today” is gradually revealed to be weirder than we thought it was.

The various plot trajectories revolve around a common center of gravity called Overman 3000, “Overman” being a thinly-veiled analog of Superman. It’s an artifact of the ’90s, when DC Comics editors boldly greenlit “transgressive” reboots of beloved golden-age franchises and magazine editors breathlessly declared comics not just for kids anymore. The fictional comic is written by Simon Magnus, an anarchic visionary with occult leanings who, while not quite a thinly-veiled analog of Alan Moore, borrows from that writer’s stock of colorful attributes.

Overman 3000 takes the familiar tropes of the Man of Steel myth—alien origin, secret identity, girl reporter love interest, bald billionaire nemesis—and pushes them to their limit and beyond, to the literal end of time. Its grand climax, which pits the superhero as the avatar of pure spirit against a villain transmogrified into the personification of meatspace, is a kind of latter-day gnostic scripture, a lurid orgy of cosmic destruction and rebirth. This story-within-a-story both reflects and influences the slightly-less melodramatic character arcs of the “real” characters in the novel.

In its mixture of literary ambition and old-fashioned showmanship, Major Arcana is a throwback to the efflorescence of popular literary fiction in the mid-late 20th century. It bears some superficial similarities to one of the hallmark works of that period, Robertson Davies’s Deptford Trilogy. That saga also starts with the seemingly inexplicable suicide of a Golden Boy, then spirals outward to follow a cast of eccentric characters, whose various destinies diverge wildly before converging again at the finale. Like Pistelli, Davies was a student of hermetic lore; both works are studded with esoteric references. But Davies’s work now reads like a relic from a lost world, a storybook world; a single history connects his novels back to those of Dickens and Hugo. Pistelli is writing after the end of history, and he knows it.

Life in the digital age is fragmented, discontinuous. How do you tell a coherent story in an incoherent age? It’s no wonder that many new novels forego the epic in favor of the miniature: the precision portrait of a particular subgroup, or the shifting lens of the author’s own subjective awareness. But Pistelli is out to prove that it’s still possible to paint on a big canvas. Major Arcana’s nine major characters represent a diverse set of identities, encompassing three generations and an unspecified number of genders. They share in common the experience of growing up after all the rules and expectations about growing up have been discarded. These are characters who must construct themselves out of the materials at hand: books, chance encounters, and various bits of cultural detritus. The personalities that emerge are complex, unstable, and a bit artificial, heightened-for-effect.

This operatic quality comes through especially in the book’s climactic sequences. Here, Pistelli piles on the sturm-und-drang without restraint—lightning even crackles on the horizon as characters launch into their aria-like monologues and fates are sealed. Though it begins in the neighborhood of realism, the novel ultimately lands somewhere in the realm of fantasy, though the segue is so subtle that one might not realize it until well after-the-fact, if at all.

Does each character represent a figure in the titular Arcana? It’s easy enough to identify Simon Magnus, the comic book writer, as “The Magician.” This is the arcana of action-without-effort, and Magnus refuses to be pinned down. “The Empress,” which is the arcana of sacred magic, might equate to the young manifestation coach Ash Del Greco. And the elusive Jacob Morrow, whose death kicks off the plot, is surely “The Fool.”

These three characters are in desperate search of transcendence, impatient to shake off all forms of constraint—not just the authority of parents, bosses, and priests, but that of nature: the body, and time itself. Other characters serve as counterweights, making the argument for living and dealing with the world as it is. The most eloquent case for fleshly existence is realized in the character of Diane del Greco, Ash’s mother, a woman of artistic and intellectual talents who consciously embraces the life of a suburban vulgarian and un-lapsed Catholic. Every major character is rendered empathetically, and we get a window into every point of view. But Pistelli’s sympathy seems to lie with the Devils, if only because he gives them the best speeches.

The book’s perspective on gender avoids collapsing into any predictable political take. Its two pivotal characters are both transgender, but what they’re ultimately seeking to trans isn’t merely gender, but materiality. Whether this is good or bad is left for the reader to decide. While it’s possible to read both characters as monsters, it’s equally possible to see them as heroes. Pistelli reserves his satirical judgment for those more minor characters who seek to put the rebel angels into politically conventional boxes; placing the transhumanist enterprise within the centuries-long context of Western expressive individualism, he lets us see them in a cosmic frame, as they see themselves.

The novel is liberally seasoned with allusions to writers of transcendental yearning: Dostoyevsky, Melville, and especially that great-granddaddy of the graphic novel, William Blake. More than two hundred years ago, at a time when Enlightenment rationalism claimed to have settled all the great questions, Blake proclaimed the idea that human nature could never be defined—that human beings would always strain toward the infinite. His prophetic works ultimately helped usher in the Romantic counterrevolution. Major Arcana hints that we might be living through a similar moment: The metanarratives may have all been deconstructed, but metaphysical desire lives on. The kids will pick up the pieces and make something mind-blowing. Might the lockdown generation, algorithmically sorted and managed as it is, even now be gearing up to risk everything for love? Stranger things have happened.

Click below to purchase this book through Bookshop and support your local independent bookstore:

Rain Taxi Online Edition Summer 2025 | © Rain Taxi, Inc. 2025