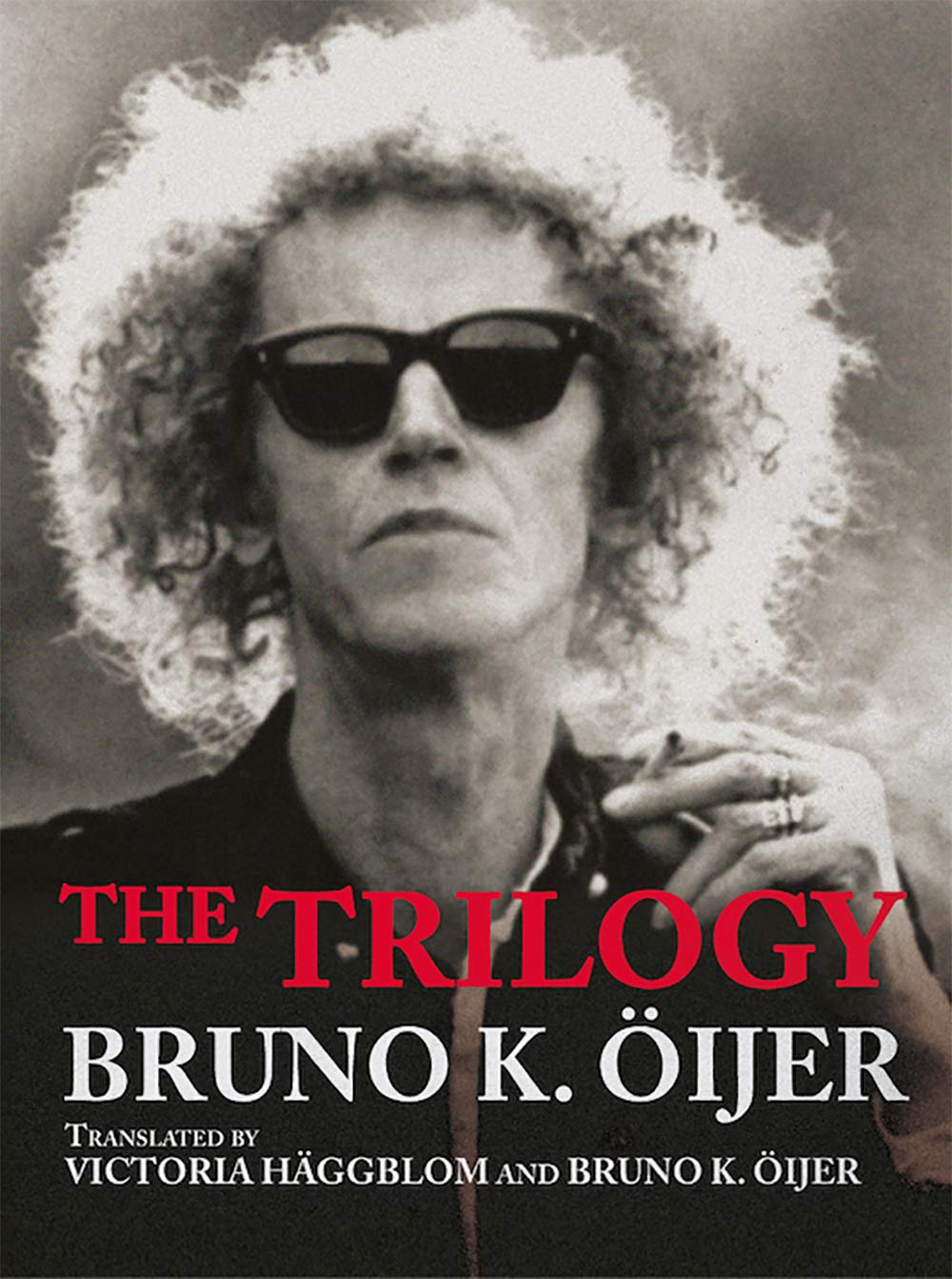

Born in 1951, Swedish poet Bruno K. Öijer has been publishing his work in his native country since the 1970s, yet to date only one of his books, The Trilogy (Action Books, 2020), is available in English translation (although as the title suggests, it comprises three books written in a series). This must change, for as humanity’s assault on the planet grows to epic proportions—waterways are poisoned, forests are felled, slaughterhouses overflow with suffering, and the climate spirals out of control—Öijer has much to say about it; his poetry confronts our exploitive relationship with nature and reveals a profound compassion for life. In this essay I will discuss Öijer’s two most recent collections published in Sweden, 2014’s Och natten viskade Annabel Lee (And the Night Whispered Annabel Lee) and 2024’s Växla ringar med mörkret (Exchange Rings with the Darkness); the translations of quoted passages are my own.

Born in 1951, Swedish poet Bruno K. Öijer has been publishing his work in his native country since the 1970s, yet to date only one of his books, The Trilogy (Action Books, 2020), is available in English translation (although as the title suggests, it comprises three books written in a series). This must change, for as humanity’s assault on the planet grows to epic proportions—waterways are poisoned, forests are felled, slaughterhouses overflow with suffering, and the climate spirals out of control—Öijer has much to say about it; his poetry confronts our exploitive relationship with nature and reveals a profound compassion for life. In this essay I will discuss Öijer’s two most recent collections published in Sweden, 2014’s Och natten viskade Annabel Lee (And the Night Whispered Annabel Lee) and 2024’s Växla ringar med mörkret (Exchange Rings with the Darkness); the translations of quoted passages are my own.

Öijer’s sense of empathy is part of a theme of lifelong alienation that has permeated his work. In “Fantasin” (“The Imagination”), the poet recounts having to write a grade school essay after summer break:

I wrote that I found an injured spider

and mended its leg with tape

when July had passed, the injury had healed

and I could release the spider

I saw it quickly scurry away in the yard

among the dandelions and grass

Öijer’s imagination reflects a nature-loving spirit (no matter that his fable also metaphorizes the imagination itself). Intriguingly, his speaker assumes the role of caretaker to a creature that many people fear and kill without hesitation. To Öijer, perhaps, imagining a relationship beyond fear may be the key to greater kinship between humans and the natural world.

Dreams are another fertile terrain in Öijer’s work. In “Drömträdet” (“The Dream Tree”), a “you” shakes the trunk of the titular tree, causing its leaves to fall and cover the ground, which then falls asleep and dreams. Perhaps this reflects nature’s cyclical essence, which doesn’t produce waste or garbage—or perhaps the ground dreams of a future beyond the Anthropocene:

dreams of the wheel tracks that are gone

the place they led to is covered with grass

only crumbling wooden crosses remain

with unreadable names and dates

Öijer cannot be called an optimist, but he does offer hope that humanity’s destructive advance will eventually be tempered. In “Romans” (“Romance”), clouds (some of which may be traces of air traffic and other sources of human overconsumption) are white wounds in the sky—yet somewhere the sky is not disfigured in this way, and “the roads must first / ask the forest for permission.” In our world, of course, other rules apply. Trees are seen not as living ecosystems but as raw materials; in “Sången”(“The Song”) the landscape is enveloped “in a melancholy, lamenting song” when a spruce is felled, and in “Asfalterade hjärtan” (“Paved Hearts”), the poet highlights the contrast between “the scent of autumn leaves” and the “piercing, unbearable sound” that has replaced it as people methodically saw down everything beautiful.

Öijer cannot be called an optimist, but he does offer hope that humanity’s destructive advance will eventually be tempered. In “Romans” (“Romance”), clouds (some of which may be traces of air traffic and other sources of human overconsumption) are white wounds in the sky—yet somewhere the sky is not disfigured in this way, and “the roads must first / ask the forest for permission.” In our world, of course, other rules apply. Trees are seen not as living ecosystems but as raw materials; in “Sången”(“The Song”) the landscape is enveloped “in a melancholy, lamenting song” when a spruce is felled, and in “Asfalterade hjärtan” (“Paved Hearts”), the poet highlights the contrast between “the scent of autumn leaves” and the “piercing, unbearable sound” that has replaced it as people methodically saw down everything beautiful.

Öijer prefers nature’s fellowship, and the wolf is one of his totems. In “Varg” (“Wolf”), he claims:

I have already

handed over my soul to the wolves

who take it with them

and wrap it in their own song

hunted on the ground and from the air

they have nothing left to prove

but run endless miles

leaving this world behind

Few animals are as misunderstood and feared as wolves, but the notion that the species harbors an insatiable thirst for human blood belongs in folklore. In his poetry, Öijer often returns to the idea that he (or at least his poetic persona) is an outcast, pursued and hunted—as is the case for many who position themselves outside societal norms and expectations—and it is this version of the wolf that Öijer writes. Figuring the wolf in this manner allows him to feel compassion for the wolf and its existential circumstances, which really are the same for all living beings. As Öijer writes in “Miraklet” (“The Miracle”):

the miracle

when a child is born

and a wolf

and a bird

and a blade of grass

The echo of Whitman here is unmistakable, and Öijer is often compared to his fellow Swede (and Nobel Laureate) Tomas Tranströmer; like them and many other poets, Öijer is a source of wisdom and a servant of life. Here’s hoping more of his work will be brought into English.

Rain Taxi Online Edition Winter 2024-2025 | © Rain Taxi, Inc. 2025