I first encountered Bhanu Kapil through BBC Radio 4 at my kitchen table in Montreal. Her voice was calm, each word carefully weighted. She was reading from her latest collection, How to Wash a Heart Pavilion Poetry, 2020), after winning the T. S. Eliot Prize. I was struck by the way Kapil connects bodily sensation to language, especially in relation to experiences of displacement and hybridity, and her words about home and hospitality drew me to explore the rest of her work. As a neuroscientist and writer, I’m interested in the interplay between biology and culture, and the embodied experiences of people at thresholds—and Kapil’s poems are investigations of these themes. Her words slice through strange intimacies; they get underneath the longings and losses of immigrants and unravel the fragments of memory and experience with greater precision than many scientific methods seem to do.

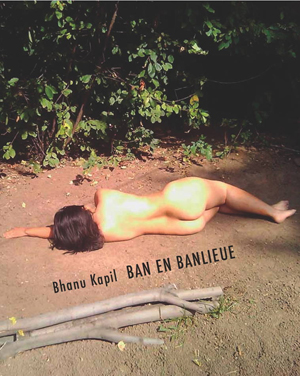

Kapil is a British-American author of Indian heritage; in addition to the T. S. Eliot Prize she has received a Windham-Campbell Prize from Yale University and a Cholmondeley Award from the Society of Authors. Prior to How To Wash A Heart she published six full-length collections, including The Vertical Interrogation of Strangers, (Kelsey Street Press, 2001), Incubation: A Space for Monsters (Leon Works, 2006), Schizophrene (Nightboat Books, 2011), and Ban en Banlieue (Nightboat Books, 2015), as well as several chapbooks. For twenty years, Kapil taught creative writing, performance art, and contemplative practice at Naropa University in Boulder, Colorado. She returned to England in 2019 and is currently based in Cambridge as a Fellow of Churchill College.

Suparna Choudhury: When I first opened Schizophrene, I was alone on the grass in June, struggling with research questions about the city and psychosis—including how to make sense of psychosis. Schizophrene created a sudden spacious opening: a felt understanding that poetry is both method and language to study the psyche, a mode of inquiry. The words and the form cut things open; they are not just experiment-al, they experiment, they investigate. Does this resonate with you?

Suparna Choudhury: When I first opened Schizophrene, I was alone on the grass in June, struggling with research questions about the city and psychosis—including how to make sense of psychosis. Schizophrene created a sudden spacious opening: a felt understanding that poetry is both method and language to study the psyche, a mode of inquiry. The words and the form cut things open; they are not just experiment-al, they experiment, they investigate. Does this resonate with you?

Bhanu Kapil: Suparna, thank you for your beautiful questions. Firstly, on “city and psychosis”—your language prompted the memory of a visit to the Chandigarh Architecture Museum, which houses an homage to Le Corbusier complete with faded originals of his correspondence with Nehru. In an out of the way corner, facing away from the flow of museum goers, I saw this fantastic thing, the “Hyperbolic-Paraboloid Dome of Assembly”:

I thought immediately of the Wertheim coral reef (crocheted in the hyperbolic plane) that I’d seen at Denver’s Museum of Contemporary Art earlier that year. Was I attending a workshop? I remember crocheting something inexpertly. I remember asking Margaret Wertheim a question about schizophrenia and the brain. A conclusion: the topology of the schizophrenic brain is hyperbolic. I am simplifying the conversation, but it was remarkable to me that there in India I encountered a third iteration of the term. Architecture and psychosis: discuss.

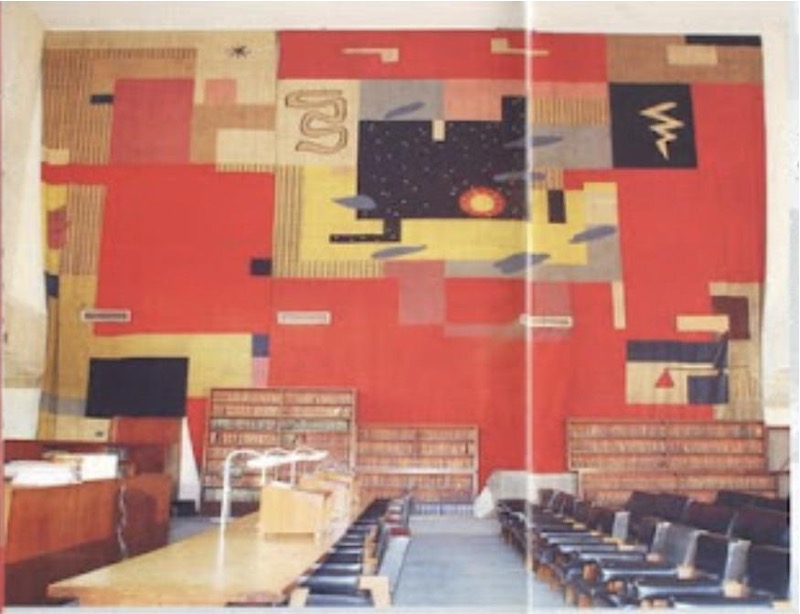

I spent long summers in Chandigarh, the city I want to answer your question with or through. As a child, I can recall the cadence of a Corbusean city block in which “the endless rhythms of balconies and louvres on its long facade are punctuated by asymmetry . . . geometry . . . the texturique” (from Le Corbusier’s planning notes). In the museum, I also saw the tapestry designed by Le Corbusier for the Capitol Building, replete with lightning bolt, cobra, and inverted red triangle, symbols of tantra:

How does this image fuse questions of psyche and city? It’s not a map, and yet it feels like a kind of map.

In the art museum next door, I attended an exhibition of ghost-animal, demon, and angel-human Mughal miniatures. From the windows, I kept glancing at the Corbusean plaza. I observed a baby Jesus in a yellow dress, an “angel on a composite animal” (as per a caption from the exhibition). I saw a concrete landscape of outsize abstract symbols, derived from theorems, decaying and water-stained in the sun.

Chandigarh is a post-Partition city, built as a new capital after the trauma of the short war. “Gold was polished with a tiger’s claw,” I read in another caption. I remember mermaids, the Buddha’s footprint indented with geometric flowers. There was a terracotta fragment of a hand holding a rotted wreath. Outside, there was a sky the color of butter. On my last night in Chandigarh, I went to a Mother Goddess ritual (puja) in a Shiva temple. A mendicant in an intensely violet sari and turquoise blouse, her hair in dreadlocks, took a central position on the green baize mat next to the fire (cobra) pit.

“Everything is folded here. Think more about what a fold is. Think more about color, geometry and the circulation of symbols in an architecture without end.” That’s a note from a blog entry now deleted, the documentation of that visit.

SC: I’m not sure what it is about your work, but sometimes it seems convulsive, creating openings through rupture. It feels fleshy. What is your relationship to skin—your own or anyone else’s?

BK: To think skin is to think its wounds, and to learn about wound care. I think of the legs of someone I loved, covered with silver scars. Dark brown skin. He died many years ago, but I still recall those scars which were also indents, flesh that had a story to tell.

If experimental writing ruptures skin, then to be clear, I don’t think that’s ever a good idea in actual life. In life, I prefer an intact boundary. Rupture is exhausting.

The sentence is the portal, the place that keeps opening. I am trying to write sentences so slowly that they might become something else. In this way, perhaps even the portal can re-set by closing itself, for as long as it needs to.

SC: There is something tentacular and deeply sensory in your work that ends up creating temporary shapes for homes—like molehills—for the feeling of displacement in your reader. I don’t mean that they are comfortable sentences: They get at disarray and dissonance in ways that feel impossible to articulate in everyday life, in ways that give expression to that vertiginous feeling that occurs when something happens—with an intimate partner, with an old photograph, with the remnants of a dream—that pierces the core of unbelonging. I drink up those lines because they make me feel understood. In that way, you create little homes, homes that have texture. (Perhaps because fault lines, the way I feel them, are taut and spiky, the opposite of silk or sand dunes.) How do you do that? Do you mean to?

BK: I am not quite sure, but it’s so helpful to read your language about something I don’t intend, or don’t imagine in advance. Perhaps the quality you describe happened, most effortlessly, on my blog, a quotidian space, a space to think about teaching but also to document the ritual time with friends by the river, or in other places. I wrote Ban en Banlieue right into my blog. These days, my writing feels private, minimal, undeveloped, and stilted. One thing that’s changed is that I am asking questions about home and belonging, but directing them at this other kind of reader, a non-genetic descendant, the person who might be reading these notebooks twenty or thirty years from now, at the limit or beyond the limit of my own life span. I hope that this other kind of poet might experience what you experience, Suparna. I wonder what a day will be like in 2079.

SC: Do you remember when we met in Cambridge on that sofa and I told you I’m from NW9? We felt strange in that room in Cambridge, and we talked about the bus and the roundabouts between Ruislip and Queensbury that we could both conjure up. You told me about your piece in The Yale Review that describes Kingsbury. I couldn’t believe you put my hood on the map. What does it feel like for you to return “home”? Is home north London?

BK: West London feels like home, yes, on the bus. And at the same time, having been in the U.S. for the bulk of my adult experience, I can’t say that that’s reciprocal. Does the home I am returning to experience suction? Can it smell me in turn? There’s no family home, for example, that I can slip into, and no way of recreating one that resembles the one we had.

An experience I had soon after returning really stayed with me. I was waiting at a bus-stop. The son of my father’s oldest friend walked by, someone I had seen on so many Friday or Saturday evenings of my childhood. He said a brief, polite hello, then kept walking. In that moment, which caused me brief, sharp pain, I realized that people and places and scenes and moments that had crystallized in my diasporic heart, or time, had faded at their point of origin. I had faded from the memory of the place I was from, something made complicated by my non-native, non-white British status.

That said, I feel a sense of home in the company of other poets. Diaspora poets feel like family. I’m grateful to know them and to be able to spend time with them in the unexpected present of being here again.

SC: Your writing exposes lines and cracks and the violence of living with/as fragments. How do you (or how should we) create moments of cohesion?

BK: Sometimes I think this is what a performance might do, more than the writing itself. I am thinking of the experience of collaborating with a young British-Pakistani writer/dramaturg/performer, Blue Pieta, and their own collective of musicians and movement practitioners. We’re rehearsing now for a performance at Soho Poly this Autumn, derived loosely from How To Wash A Heart, my last book of poems. In our rehearsals and emails and conversations, we openly talk of what it is to share imagery. Can ancestral trauma be discharged, through our bodies, during these performances which decrystallize images and let them flow as voice, the text that’s now a score and also gestures, dance?

SC: Do you still practice bodywork?

BK: My bodywork practice was a deeply moving and practical part of my life since my twenties. I am not sure, as someone who now identifies as a caregiver, that I would have the capacity to set up a practice in the UK. I did have a chat with a local salon about an unused room at the back of their building, and the potential to share it part-time with a local reflexologist. We’ll see.

Bodywork is exorbitantly expensive in the UK, and I’ve noticed there is less training or expertise when it comes to soft tissue or orthopedic approaches. I love to offer or receive bodywork at home—my table is always set up; I can see it from here!—and to think, that session would have cost a hundred pounds!

SC: Are you a heavy dreamer? Do you wake up with impressions, affects, details or all of it? Do they enter your work?

BK: I dream intensively, and I record my dreams. Each year, on December 31st, a “void” night, I dream for someone else, asking their permission first.

I am not sure that what I dream enters my work. A parallel daily practice is mandala drawing. I recently drew something I did not expect to draw: a person carrying a load of firewood on their back, entering the trees. I am writing a novel of the jungle, of walking into the jungle as a child and spending the night there, and somehow this figure began to speak, and spoke in my writing later that day, as if to say, follow me. So, there are elements of active imagination, or extended imagination, to writing like this. I think the issue with drawing from dreams is that I tend to scrawl them down very fast, so they are less legible when I return to my notebooks for an idea.

SC: How do you wrestle with ghosts? Ancestors, lost lovers, past versions of you, old homes?

BK: I haven’t, when it comes to my time in Colorado, shed a sense of ongoing loss. That loss is related to being with others in ordinary ways. Coffee with a neighbor in the morning, hooting like an owl as I walked down the alley with my dog—that was her signal to put the kettle on. Or, every August, another friend would come through town, and text me LAKE SWIM. Off we’d go to swim in a freezing mountain lake. My soul longs to swim in that lake, and to drink the delicious coffee.

Rachel Pollack, my former colleague at Goddard College, had this amazing card, The Ghosts of Healing. It doesn’t have that name in any book, it’s just what she called it, and it’s the last card she selected when she “blessed” my art deck, of her own Shining Tribe Tarot. Energies rise from stones in a cave, holding roses at their hearts, and without true shape. What is the difference between an ancestor and a ghost? My longing is to spend time with these energies and to receive them, to listen to them deeply, and to hold my seat in the face of anxiety and fear, a response to their arrival in the first place, as Rachel pointed out.

There was a past version of me who taught three three-hour experimental writing seminars a week for twenty years at Naropa University, or twice a year at Goddard. It’s been an adaptation not to be teaching in that intensive way, and at the same time, to figure out other ways to be with poets, or to be one myself. I am no longer sure if I am a poet in the way that I thought I was. I feel like a twelve-year-old version of me, sitting on the windowsill and longing to write.

SC: Sometimes I become such a stranger to myself when I speak my mother tongue. Is your tongue at ease in languages other than English?

BK: I speak broken Punjabi/Urdu/Hindi mixtures to a variety of people, but I feel ease and peace in the gurdwara listening to an archaic language, the poetry and sound vibrations of the Sukhmini Sahib being read/sung aloud. It feels good to have more of these mixtures around me/us than was possible or available in Colorado.

I understand the strangeness. The mouth formed its shape around the alphabet we spoke. What is a mouth?

SC: What is grammar [doing]?

BK: It’s absorbing something, then releasing it, like a cloth soaked in water.

SC: At Poetry Clinic, an epistolary apothecary of poems (at which you’re going to be resident poet soon, thank you!), the premise is that poetry can do something, something that will equip our imaginations to deal with uncertainty and suffering. What do you mean for your poems to do to people?

BK: I think I don’t mean or intend or pre-hope anything for my poems. Where they arc and lodge or fall or reach is not something I can ever know or predict. I’m hoping that the experience of the Poetry Clinic will be what you dream it is. How will we know?

SC: Your work and my current interests lead me to ask you: What is wilderness to you? What remains wild?

BK: The wilderness is a jungle at night. Night has fallen, or is about to fall, and it’s too late to turn back. You reach a puddle. Should you skirt it by taking a wider, less certain path through the trees, or go straight through?

Memory is wild.

That particular memory is a memory of wildness that I am trying to write. My epigraph comes from a poem by Alejandra Pizarnik, translated by Cecilia Rossi: “All night, I walked into the unknown rain.” That’s what I’d like to do.

Click below to purchase these books through Bookshop and support your local independent bookstore:

Rain Taxi Online Edition Fall 2024 | © Rain Taxi, Inc. 2024