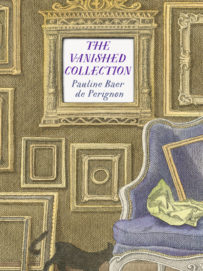

Pauline Baer de Perignon

Pauline Baer de Perignon

Translated by Natasha Lehrer

New Vessel Press ($17.95)

by Linda Lappin

Despite belonging to an illustrious family of art connoisseurs and actors, Pauline Baer de Perignon felt she had never really tapped into her own artistic potential. A journalist, screen writer, and teacher of creative writing, she had never personally completed a book or found a writing project exciting enough to galvanize her energies. Then a casual remark by a cousin proved to be life-changing, leading her on a treasure hunt during which she made some startling discoveries about her family and recovered priceless heirlooms that everyone thought were lost forever. This search comes together in The Vanished Collection, a work of nonfiction which entwines a disquieting family memoir with a true tale of mystery and intrigue.

De Perignon’s great-grandfather was Jules Strauss, a celebrated Jewish art collector in Paris whose magnificent collection of Impressionist paintings had supposedly been auctioned off in 1932. That sad date marked the end of the family fortunes, but the author knew very little about her great-grandfather, certainly not why he had parted with the collection he had so passionately built. Her family had never talked about that chapter of their history—nor had they ever spoken much about their Jewish origins; de Perignon’s father had converted to Christianity at the beginning of the war, and she had been raised Catholic. Jules Strauss was a faraway figure she had never thought much about.

Then, out of the blue, her cousin Andrew, an art expert, suggested that their great-grandfather’s collection had not been auctioned in 1932, but was stolen by the Nazis. “Andrew’s words,” she writes, “sent my mind tumbling down a rabbit hole: I couldn’t tell if the effect was pleasant, bizarre, or anxiety-inducing. . . . The fragments of family history Andrew evoked were profoundly unsettling.”

Andrew provided her with a list of masterpieces by Sisley, Monet, Degas, and Renoir for which their grandmother had unsuccessfully filed claims from 1958-1974. Originally in the Strauss collection and then confiscated by Nazis, some of these works had been returned to France in the aftermath of the war, but not to their rightful owners. Some were still being held in storage in French museums. Others were elsewhere in Europe.

De Perignon soon became obsessed with investigating Jules’s life. She was puzzled by the reticence she initially ran up against: Why had no one in her family ever mentioned this story before? Jules and his wife had remained in Paris during the Occupation, while other family members and friends fled or were deported. When forced to move from their home, they were stripped of nearly everything they owned, including all objects of value. Their apartment at 60 Avenue Foch, requisitioned by the regime, became the headquarters of the SS’s black-market operations. But the Strausses were never deported. How had they managed to stay alive in occupied Paris?

All this pointed to yet another mystery. Where were the paintings now, and could anything still be salvaged? To find the answers, de Perignon quickly gained highly specialized research skills, and assisted by curators, art historians, and archivists, combed through museums across Europe to retrace the scattered pieces of Jules’s collection and to make new claims for their restitution. She also pestered her older relatives with questions, scrutinized Jules’s personal papers, and even consulted a medium who channeled his spirit.

The results were impressive: Not only did the author succeed in recovering two artworks for the family, but she uncovered forgotten angles to Jules Strauss’s contribution to the history of French art and reconnected to her Jewish heritage. In the process she discovered much about herself, noting that “the women in my family have always remained in the shadows, their qualities often ignored. But here, in this Paris suburb, in this archive where no relative of mine has ever been, and where no one was expecting me, and where I would never have imagined setting foot, I could finally be myself. . . . This was where I belonged.”

The restitution process was both painstaking and painful, but de Perignon’s efforts were rewarded with the return of a painting, “The Portrait of a Lady as Pomona” by Largillière. Previously in possession of a museum in Dresden, it now hangs in the author’s living room: “When the house is empty, the children at school, the cat purring on the couch, I pause in front of the portrait. We look knowingly at each other. Only I understand the journey she has taken, only she understands my quest.”

Having made that quest with her, readers must agree with an insight offered by “Jules” through the medium: “Truth is only possible when history is acknowledged.” In The Vanished Collection, de Perignon pierces through the silence of family and bureaucrats, unpeeling layer after layer of amnesia and deception to retrieve not just a painting, but a deeper portrait of her life.