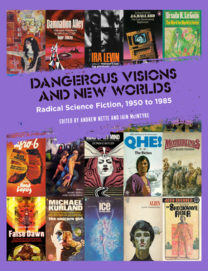

Radical Science Fiction, 1950-1985

Radical Science Fiction, 1950-1985

Edited by Andrew Nette

and Iain McIntyre

PM Press ($29.95)

by Paul Buhle

About a half century ago, my grand aspiration was to become a Science Fiction writer. It wasn’t a bad idea. The half-dozen or more SF or SF/Fantasy magazines on the newsstands published hundreds of stories each month, and the paperback market was similarly booming. Some of the 35-cent paperbacks tackled serious subjects, like the commercialization of culture; the more avant-garde writers offered literary polemics against racism and war. And although I couldn’t see it, the revolution had only begun. PM Press’s recent anthology Dangerous Visions and New Worlds: Radical Science Fiction, 1950-1985 covers the field’s early years with wonderfully sweeping essays and studies of some of the most illuminating authors and editors of the field in transformation.

From a radical point of view, the “Futurion Club” of Manhattan, formed during the Popular Front years of the later 1930s, offered a beginning. Comprised of mostly Jewish writers, it included Isaac Asimov (the only genre writer, along with Rod Serling, to have a whole magazine eventually named after him), but also figures like Donald Wohlheim, destined to become more influential as editors of SF magazines and of their own paperback imprint series, and Judith Merrill, the feminist writer who anticipated so much to come.

One of the astounding and revealing documents in Dangerous Visions and New Worlds is a reprint of two facing pages of writers for and against the U.S. invasion of Vietnam. This literal face-off is useful because it stands for so much more. The audience for magazines and books, until at least 1960, was considered either juvenile or juvenile in mind, a similar assumption to that made about comic art and similarly maddening to more mature creators and fans. Bug Eyed Monster traditions had been nibbled at the edges by writers who managed to suggest that encounters with aliens might be a lot more complicated, or that civilization after a widely anticipated nuclear war might not rebuild by the same rules, or that the State—even the U.S. State—might be dangerous for individual liberty. That last point cut across Left and Right, reaching a rapidly expanding fan base and offering promise to a relative youngster like Philip K. Dick, an anti-authoritarian who could seemingly be Left and Right at the same time.

But another issue had more potency for the Science Fiction of the 1960s and after: Sex. One much-remembered writer, Jose Farmer, had a global impact on SF authors with his daring plots and suggestive details. Meanwhile, the judicial repeal of censorship laws offered cash galore for the small-scale producer as well as for the more daring movie corporations. One of the most intriguing essays in Dangerous Visions and New Worlds reveals the creation of soft-core lines of SF books with circulations in the tens and hundreds of thousands. This was a boon to enterprising authors who could grind out lascivious wordage at record speed, including prolific gay authors such as Larry Townsend. Older readers who shunned sexual material expressed shock at even muted effects on the mainstream writers and magazines. Those older readers counted for less and less as the counterculture advanced, however.

Dangerous Visions and New Worlds is unique in presenting an extended discussion, through several topical essays and extended comments in many others, of race, gender, sexuality, and ecological subjects in these works. The role of Harlan Ellison, editor of the totemic 1967 anthology Dangerous Visions and its successors, was surely crucial as he opened doors and made things possible. So did the only major figure of this volume still living and writing today, Black and gay author Samuel R. Delaney. Also mentioned for her contributions is the late Ursula Le Guin, whose feminist and antiwar breakthroughs made her internationally famous, and not only to SF readers. Similarly, Octavia Butler, whose untimely death at 62 deprived readers and the field of a Black, feminist writer who had already made large waves, is noted for her anticipation of Afro-Futurism.

But there is much, much more here. Consider the curious life and role of Alice Sheldon, married to a CIA chief but in her own mind an unrealized lesbian with a powerful imagination. She wrote as “James Tiptree, Jr” for more than thirty years and began to win awards in the 1970s for stories that mixed sex, drugs, and space exploration. Sometimes in her fiction, thanks to scientific advancements, men become entirely unnecessary—a far cry from the Space Westerns of yesteryear or Star Wars et al.

Considered also in the anthology is the changing shape of prose. Fans of the fantastic who welcomed a break from the old staidness of form drew back from literary experimentalism in the genre, which first began in the UK through the magazine New Worlds. Plots could disappear into prosy explorations of what language might do in untrammeled worlds. Old time editors complained, this time with a certain validity, that the result was fascinating, but perhaps not actually Science Fiction. Mainstream writers like Joanna Russ, a feminist notable, seemed at times closer to James Joyce than to Ursula Le Guin.

The SF field at large was transformed again a few years later by blockbuster films, as if nothing could compete with the themes of the big screen. The pulps had by that time long since dwindled, anticipating the near-total collapse to come. Dangerous Visions and New Worlds happily stays away from post-1985 developments but gives us ample hints of the better energies and directions of the field’s evolutions and a clear vision of where it came from in closely viewed literary terms.

There are many more treats to be found in this volume. The essays in this collection may lead readers to consider African American author Joseph Denis Jackson’s forgotten 1967 “insurrectionist” novel, The Black Commandos, or Hank Lopez, the leading Latino spirit in SF. Likewise, readers might be drawn to reconsider household names, such as leftwing feminist poet and novelist Marge Piercy and her 1976 classic Woman on the Edge of Time.

Le Guin and the best of the others elaborated the simple truth that as things go on changing drastically, present-day organized society appears in no way ready to understand them, but if they can be seen to take place on a different planet and/or in the future, they might be understood more usefully. Basic human understandings of everything from gender to economics need to change, to be seen differently, or society will surely perish.