Katie Peterson

Katie Peterson

Photographs by Young Suh

Omnidawn ($19.95)

by Rachel Slotnick

To call Katie Peterson’s Life in a Field unsettling is an understatement. The collection eludes narrative and logic, insisting on hybridity. Readers must remind themselves to embrace confusion and linger in the discomfort. The point is to get lost in the field.

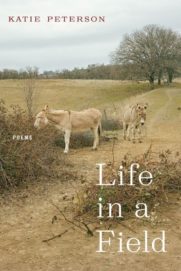

“Follow me,” Peterson seems to say in her opening lines, initiating a fable involving a girl, a donkey, and a secret. Almost immediately, we are confronted with maternal separation, followed by a gruesome breeding pattern. In these words about a farm animal, the reader discerns a thinly veiled critique of our society’s obsession with control over women and uteruses. Alongside the donkey, there’s the girl growing into puberty: her “hips widened, her breasts began to require confinement.”

There is an urgency to these poems. The aforementioned girl swims downstream, paired with a photograph of a child in her baptismal pool. “Do you want to know if she swims naked?” Peterson teases. My eyes travel the rigid face of the girl in the photograph, a stranger to her body. I think of the donkey, failing to recognize his mother. “When you work with animals,” Peterson writes, “they are always moving out of the picture.” But there is this girl, trapped in the frame.

In the poem, “HEARD IN CHURCH,” we read of the “Man who rode the donkey / Greatest cowboy of them all.” Donkeys are adorned with a dorsal stripe, a bisecting pattern beneath their fur, said in liturgy to be the shadow of the cross. “They call them Jerusalem donkeys,” Peterson writes, “and they are prized.” With this revelation, the poems take on an accusatory tone. What are we to make of human behavior, tearing this holy creature from his mother and putting him to work in the field? Peterson’s poetry makes one uneasy, but the disease is beyond the page.

Without flinching, the narrative returns to maternal separation. “If you lose something, for example if you lose a baby, you might wish for another. But if you lose another baby after that, and this time you are farther along, there are two different paths the mind might take.” Peterson debates the logic of wishing for one healthy baby as opposed to wishing for two. She enumerates the second path, “well, it’s not a path, it’s a person—the second person wishes for two babies, because now two are owed him or her.” The mathematical intonation is heart-wrenching here, reducing miscarriage to a word problem in which two trains are leaving the station at different times.

We can’t ever quite return to the fable with which the book opened; everything has been transformed through the lens of what we now know. Of donkeys, Peterson writes: “Most families can only afford one,” and now the donkey has shapeshifted to an unborn child. Thematic words seep through, refusing to submit to the child’s realm in which Peterson originally attempted to contain them: “the afterbirth of his nervousness,” jolts our attention, while “our second try has given birth to something small” sits unnervingly in our mind’s eye.

The story then splinters into metafiction, addressing the reader’s discomfort directly. “This story is not your story. You are not meant to relate to it,” Peterson writes, and there it is: She absolves our distress, in much the same way as a confession might absolve sin, allowing for a bit of confusion. “You are meant to pitch a tent inside this page like a down and out person might do by the American River . . . You are meant to believe you can live here.” But we don’t want to live in this story. It is uncomfortable, it is lonely, it is provocative, and it is familiar.

“What do you do with the story you didn’t wish for?” In the closing pages of Life in a Field, the girl and the donkey are faced with the tragedy of the climate: falling skies, droughts, brushfires, and floods. “This story intends to refute the creation of the world,” Peterson writes. “As it says in the Bible, I appeal to you on the basis of faith in things not seen.” Does poetry require faith? Are words things unseen? What if the field in which we linger is merely a paragraph, a collection of nouns and overgrowth? Poetry, Peterson warns, is not meant to be a palliative. In the final photograph, a woman wears a donkey mask. Or perhaps, a donkey wears a woman mask, braying for help.