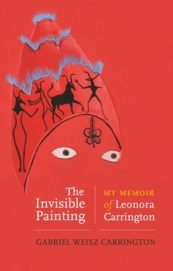

Gabriel Weisz Carrington

Gabriel Weisz Carrington

Manchester University Press ($26.95)

by Patrick James Dunagan

Gabriel Weisz Carrington’s The Invisible Painting: My Memoir of Leonora Carrington shares the author’s memories of growing up in the Mexico City household his remarkable mother, surrealist artist Leonora Carrington, created with his father, photographer Emerico “Chiki” Weisz. The book gives an intimate, at times albeit fleeting, glimpse into the real world of his mother and her work.

Raised in Cockerham, England, where she was ensconced in her well-to-do family’s “Victorian mansion,” Carrington fled to Paris as soon as she possibly could, where she quickly met up with the Surrealists. Possessing a profoundly strange beauty—in many photographs a disquieting, haunted aura envelops her face as if she has just been shocked into recognition of consciousness—she wound up living with artist Max Ernst in a rather idyllic small town in the southeast of France until Ernst was jailed by the Vichy government. After this, “locals, who both hated and envied the life she led with Max, turned their backs on her,” and Carrington ended up in Spain before being institutionalized for a time. When her father attempted to send her to South Africa for further institutionalization, she married the sympathetic artist and diplomat Renato Leduc in a burst of desperation, then fled to New York City and on to Mexico City.

Ernst also ended up in New York City, marrying the heiress Peggy Guggenheim. Weisz Carrington includes here a group photo of expatriate artists. Ernst sits in the second row with his adult son Jimmy (from his first marriage) and Guggenheim standing behind him. Carrington sits on the ground in front of him to his left. Friedrich Kiesler, casually lounging beside her, stares at her rather than facing the camera like everyone else, while Stanley William Hayter sits on her other side with his face partially still turned towards hers, as if he had looked towards the camera just in time. Between the two men, Carrington stares intently forward, ever steadfast in her “refusal to be treated like a sexual object.” Notably, Guggenheim and photographer Berenice Abbot are the only other women in the photograph of fourteen “artists in exile.”

Ernst also ended up in New York City, marrying the heiress Peggy Guggenheim. Weisz Carrington includes here a group photo of expatriate artists. Ernst sits in the second row with his adult son Jimmy (from his first marriage) and Guggenheim standing behind him. Carrington sits on the ground in front of him to his left. Friedrich Kiesler, casually lounging beside her, stares at her rather than facing the camera like everyone else, while Stanley William Hayter sits on her other side with his face partially still turned towards hers, as if he had looked towards the camera just in time. Between the two men, Carrington stares intently forward, ever steadfast in her “refusal to be treated like a sexual object.” Notably, Guggenheim and photographer Berenice Abbot are the only other women in the photograph of fourteen “artists in exile.”

After arriving in Mexico City, Carrington’s marriage with Leduc naturally faded away. As Weisz Carrington nonchalantly describes, “As the years went by, she met my father, Chiki, and they decided to live together.” Each of them had had their own near fatal dalliances with the Vichy government; coming together no doubt gave them opportunity to benefit from the mutual support and understanding of each other’s difficult personal past. Living in Mexico City, they joined the many fellow artists, writers, and thinkers who had fled Europe as the Nazis advanced during World War II.

Having now raised a family of his own, Weisz Carrington still lives in the same home, which creates interesting opportunities for reflection:

The table where I now sit was a meeting ground where we discussed politics and art as well as the more trivial details of our day-to-day existence, all the while sharing food, each of us serving ourselves from the kitchen. It was a place where we could establish our identities and share the challenges life brought us. During these meals, we would choose whichever words best expressed what we wanted to say; sometimes, those words would be in Spanish, sometimes in English or French, as each language carried its emotional substance. We referred to this mixture as ‘volapük’, a term coined in the nineteenth century by Johann Martin Schleyer to describe a mixture of English, German, and French. If only I could go back and be a fly on the wall during those long-ago conversations between Edward James, Luis Buñuel, Aldous Huxley, Octavio Paz, Remedios Varo, Wilfrerdo Lam, Alice Rahon, and all the others who at one point or other sat around this very same table, enjoying themselves, gossiping and laughing.

We do become privy to how Carrington’s behavior could mirror the real yet unreal appearance of many of the creatures that populate her paintings; Weisz Carrington shares how, “she often behaved as though our whole lives were an ongoing conversation briefly interrupted by the practicalities of day-to-day existence.” he was providing a typical home life, yet one filled with extraordinary and unusual emphasis upon esoteric and arcane occult knowledge. Occasionally, there was discussion of her work: “She spent hours learning about and practicing meditation, and she kept a sketchpad next to her bed that she filled with drawings and notes. ‘My paintings don’t come exclusively from dreams,’ she once declared. ‘Some scenes emerge from altered states of consciousness. Others—who knows where they come from.’”

For those readers already invested in Carrington’s art, it’s difficult not to desire something more from this memoir—foremost a bit of that “fly on the wall” perspective the author himself yearns for. Weisz Carrington offers some notable reflections upon works by his mother and a few books of hers in his possession, and succeeds in conveying the atmospheric qualities of growing up in her presence, yet in the end the son’s writing is, perhaps inevitably, only a pale reflection of the mother’s accomplished art.