by Don Cummings

Good thing I came down with the flu. My shepherd into the publishing world, Lisa, and her husband, Vito, came to Los Angeles for a visit. We were on our way to Cambria, a small town four hours’ drive north, and we stopped in Buellton at Industrial Eats for lunch. As we were finishing up, I knew something terrible was happening at a cellular level; by the time we arrived at our Airbnb, I was an unhealthy disaster. The disease lasted three weeks.

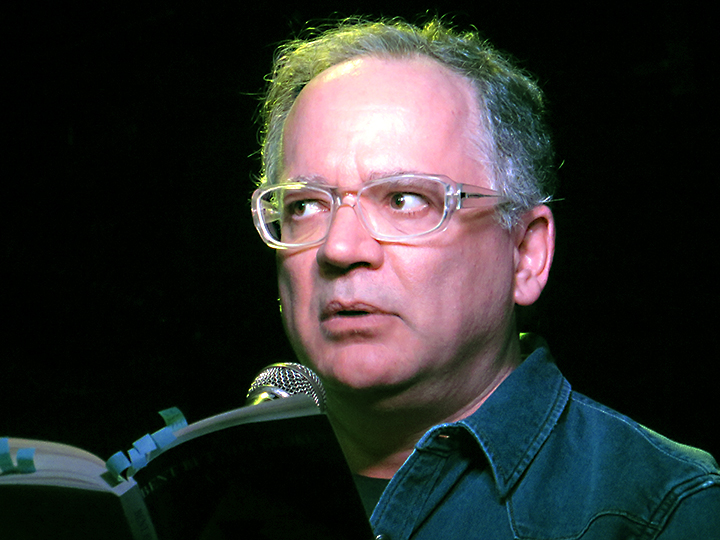

But I lost weight—tons of it. So instead of having to get on our new elliptical machine in the garage, I just had to get better. And I did. Ready for my book launch, my cheekbones cut back into existence, I could show off my bio-bag without too much embarrassment. I learned, however, how quickly weight can return, especially when eating at overly-rich restaurants and drinking a bit too much to deaden the anxiety of having to talk to too many people. I also learned it’s never a good idea to be over fifty on your first book tour—even if you still have a little hair on your head.

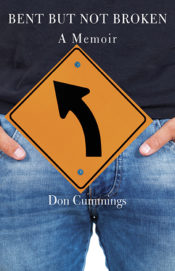

I wrote a memoir about my penis, the part of my body that was suffering from Peyronie’s disease, entitled Bent But Not Broken; my aim was to discover my emotional relationship with my body, my husband, and some of mankind. I was sort of happy to go on the road to read out loud. Memories from when I was young, thin, and handsome reminded me that it was a joy to parade in front of people. But now? Why on earth was I leaving the house when unwanted pounds can boomerang back so quickly? Writers are introverts, and by brutal will I had become one just like the rest of them; happy to be peacefully sitting at my desk in sloppy drawstring pants, I loved not being looked at by anyone.

I wrote a memoir about my penis, the part of my body that was suffering from Peyronie’s disease, entitled Bent But Not Broken; my aim was to discover my emotional relationship with my body, my husband, and some of mankind. I was sort of happy to go on the road to read out loud. Memories from when I was young, thin, and handsome reminded me that it was a joy to parade in front of people. But now? Why on earth was I leaving the house when unwanted pounds can boomerang back so quickly? Writers are introverts, and by brutal will I had become one just like the rest of them; happy to be peacefully sitting at my desk in sloppy drawstring pants, I loved not being looked at by anyone.

It took a while for me to get here. Jayne, a writer I knew when I used to be an actor and had a side job in a production office as an accountant, was once a performer, and was ten years older than me. She mostly ate raw vegetables at her desk to keep her figure. I was young enough to eat enormous plates of enchiladas and still come out the other side attractive, so being a writer like Jayne, especially one in the middle of middle age, looked like torture. I could never survive on carrots. But I was sure that if I were ever to become a full-time writer, I would still be someone you would want to look at—I did not believe growing round and unappealing could ever happen to me. Ah, youth. Even worse, there was no way of guessing that I would end up with a condition that would hack away at my lovely penis, and thereby my self-esteem. Good thing the future can’t tell you what’s in store for you.

With my memoir I was happy to help the world, “one penis at a time,” but I did want to look good doing it. Ten years ago, I had a reading of one of my plays presented at the Public Theater in New York City, and the lineup included Meryl Streep. It came off well and my play was optioned for Broadway. I was being ogled by the entire commercial and not-for-profit theater community of that noisy city, and though I felt insecure, I also felt safe beneath my powder blue, not-too-tight DKNY shirt and my black chinos. All I could think of after that night when things were rollercoaster-ing along was, “At least I looked good.” And I did, though it was probably the last time I looked good in public. Three years later, I stained the shirt with tomato sauce too strong for any stain remover, but no matter, I was too fat to wear it anyway, so I threw it out. And the play that was optioned—well, let me know if you ever see it playing anywhere.

Maybe it should be considered a triumph to appear in public as one continues to look worse and worse. My Great Aunt Rose appeared at my Great Aunt Helen’s eightieth birthday party in a peach pants suit hugging every curved bit of her—but somehow, she was able to hide the lump of her colostomy bag. Perhaps it was there and we just couldn’t see it because our eyes were watering from the liters of cologne she had dowsed herself in so no one could smell her effluent. We’ll never know. But she was defiant while vulnerable: Aunt Helen told her not to wear that outfit, and yet she persisted. I have no one warning me about bad peach pants, but I don’t need outside help to put on the sartorial breaks. I know my body should be hidden, so in shame I drape my sagging, bent corpulence.

Perhaps it’s from the wine. Or the pork chops. The sitting. The aging. Of course, it’s caused by all of these and more. Drinking makes me puffy. Pork chops make me want more pork chops. Sitting hunches my back. And aging, well, as Philip Roth warned, “It’s not a battle, it’s a massacre.”

I still can’t live on carrots. I’m only half a drunk. I have to sit to write because standing makes me want to organize drawers, and I’d rather procrastinate in a more relaxed manner. And aging, I simply can’t help it much. I wanted to help others, publicly if necessary, by informing them about Peyronie’s disease—to make sure they get to a urologist to treat their penises as soon as possible, and to teach them how to deal with the psychological torment of diminishing sexual function—but like the event at the Public Theater, I wanted the safety of looking good while doing it.

No such luck. My neck was sagging at the Los Angeles launch party at Skylight Books. In New York, the venue was so hot I had to strip off my outer layer and present my material in a gut-hugging T-shirt the color of earthworms in spring puddles, showing the world just how thick I am. In Minneapolis, in a subterranean bar, it was cold and dark so I was luckily hidden under long sleeve denim, but certainly not anything special to look at. I wore a black T-shirt under my button-down, so when I had to strip down—because it got hot in there, too, under the lights—I wasn’t as disgusting to behold as I had been in New York, but old men in black T-shirts look like old men in black T-shirts.

Back in California now, I have an event coming up in Santa Barbara, and I am starving myself. Have you ever been to Santa Barbara? All the people there hike twenty miles every day when they’re not surfing, and everyone is wealthy—at least everyone who will be at my event will be—and the rich tend not to be obese. And these books only net me between two and four dollars per unit! I can’t make enough money to save up for a fat farm. I could beg my wealthy cousin, who is flying in on her private jet for the event, but she would just wisely tell me to do what she does in order to look so good: train for marathons.

I just can’t. I hate running. It makes me nauseous and hungry. They say that every author now has to be their own brand, that we are in business for ourselves, that we must market not only our work but our personas. This is the failed actor’s nightmare. Happy to forget all my lines, I left the stage and screen long ago so I would no longer have to be watched as I bloat, wheeze, and drip into senescence. But hams will be hams, just in new cans. Fate insists upon it. Oink.

Can’t I just finish my next book and have my agent pull up to the side of my house so I can toss the manuscript over the wall for her to whisk it off to New York without anyone seeing me? I mean, should writers really be watched? And knowing that we will be looked at, doesn’t this, perhaps, change how we write? The presentation of the less-than-perfect-decaying-self demands some kind of self-deprecation. Knowing this, perhaps our work suffers. It can be forced into a kind of Nora Ephron style, the hating of the neck and all that.

Or maybe Ms. Ephron was simply presenting the absolute truth of writers from antiquity to the present, and her tone is the tone of writers for all time. We all really do hate our necks. But let’s forget that vengeful part of the body. Wasn’t this all about my penis anyway? Such a relief. At least that’s something we don’t have to look at it in public—for the most part.