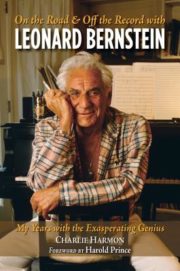

My Years with the Exasperating Genius

My Years with the Exasperating Genius

Charlie Harmon

Imagine ($24.99)

by Douglas Messerli

Charlie Harmon, the author of On the Road & Off the Record with Leonard Bernstein, worked as Bernstein’s personal assistant for four years late in Bernstein’s life, establishing a very close (if also, as the subtitle indicates, exasperating), relationship. As Harmon begins this memoir: “Before I entered his life, Leonard Bernstein’s assistants came and went like the change of seasons in New York.” Some just disappeared out of his life, while others resigned after fairly short periods; one attempted to steal Bernstein’s limousine. Others were simply not up to the demands of the job, which included everything from packing and unpacking the twelve suitcases with which Bernstein traveled around the world, making sure that the Maestro made all of rehearsals, luncheons, and dinners on time, on occasion even chauffeuring Bernstein to events, and hundreds of other duties large and small that helped ease the conductor and composer through his more than stressful life.

Not only was Harmon highly organized, but when Bernstein realized that Harmon had studied music, could play the piano, and knew how to score musical compositions, the Maestro might call him down in the middle of the night (Bernstein traveled at all times with a piano in his room) to play Don Carlo or a duet. Since Bernstein was working on his opera A Quiet Place during the first year of his work as Bernstein’s assistant, Harmon was asked to score all the instrumentals and distribute them to orchestra members.

Much of his time was simply attending events with the Maestro, meeting and making small talk with major musicians and celebrities, even dancing and singing with Betty Comden and Adolph Green. And surely it didn’t hurt that Harmon could also speak German and Italian and was a quick learner even of Hebrew.

Yet if you think that Harmon’s book might be simply a loving paean of his time with the master, you’d be highly disappointed. The Bernstein of Harmon’s book is not the well-dressed “Lenny” of the Kennedys’ whirlwind life, but the LB (as Harmon and others of his entourage refer to him) who can be rude, petulant, dismissive, haughty, unwashed, and, occasionally, downright sleazy (his own nickname for himself was “Mississippi Mud”).

From the very first moment LB’s manager, the terrifying Harry Kraut, hired Harmon, Bernstein’s private chef Ann Deadman immediately looked over the new hire, saying “He’s too cute. he’ll have to shave that moustache.” The naïve Harmon wonders, “Cuteness was a liability? Had prior assistants been up for grabs in some kind of sexual free-for-all?” Of course, Bernstein, besides having been married (his wife had died before Harmon came to work for him) and producing three children, was openly gay, but this book clarifies how avidly he sought out handsome younger men for his beds. Years later, when Harmon was introduced to Bernstein’s new chauffeur for a stay in Italy, he himself was tempted to repeat Deadman’s phrase (and indeed, the handsome driver was found in Bernstein’s bed soon after).

At first, I was a bit irritated by Harmon’s book; why air all of LB’s dirty laundry (which, in fact, was another of his literal jobs)? But as the book progressed, I began to realize that if you truly loved this talented genius, you had also to take in a fuller portrait. How else, for example, could LB not be a speed addict given how he bounced back and forth from his apartment in the Dakota in New York to Italy’s La Scala, Vienna, Israel, England, Tanglewood, Los Angeles, and his home in Connecticut—all in a single year? Without it, as Harmon was, one could hardly be expected to survive; by book’s end the author has nearly had a nervous breakdown from his endless tasks. There is even a kind of #MeToo moment when, in a hotel room, the great Bernstein attempts to grab Harmon’s crotch. The too cute gay boy pulls away, simply explaining that that was not part of his job.

Besides, it is clear that the two men, although sometimes furious with one another, had become close friends, LB even seeing his assistant as being in a kind of “marriage” with him. Harmon shares long descriptions of what he describes as the perks of this job, meeting and becoming close friends with so many of Bernstein’s celebrity acquaintances. If some might have treated the assistant—Harry Kraut included—as if he were only Lenny’s servant, many others recognized his importance to the Maestro, opening their homes and their personal lives to him.

Moreover, there are all those wonderful times with not only LB, but with his maid, Julia Vega, the chef, Deadman, and Bernstein’s long-time personal secretary, his original piano teacher Helen Coates. Not only were there hundreds of stars—Beverly Sills, Lauren Bacall, John Travolta, James Levine (who unexpectedly took over Harmon’s role so that the younger man might have one day of much needed rest)—but also queens and other royalty. And despite his dislikable attributes, LB was brilliantly witty and funny. Still, Bernstein’s own loveable mother once took Harmon aside to ask what he was really planning “to do” with his life, as if provoking him to think about what gifts other than endless sacrifice that he might wish to give to the world.

When he was told that Bernstein was ill and near death, Harmon paid him a visit at the Dakota, where the two briefly and humorously spoke of their long friendship. Harmon to LB: “You’re only the second person I’ve ever known that I could fight with.” Harmon to LB: (soon after) “Arguing isn’t the same as confrontation. When both sides agree to a compromise, a fight deepens a friendship, instead of destroying it.” LB: (in a raspy growl) “Fighting—it’s as good as fucking.” Soon after, he takes Charlie’s hand and says: “Please look after my music.”

Harmon did. After Bernstein’s death, he edited full scores of West Side Story and Candide before tackling vocal scores for Candide, On the Town, and Wonderful Town. He might have gone on to edit performance scores for others of Bernstein’s works, but Kraut, unable to see the importance of those projects, pulled the plug. Yet today people still come to him asking many questions about the scores and productions. In the end, Harmon finally discovered his own life, even without abandoning the life of his great mentor and, as he describes LB, rebbe.