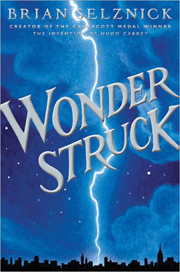

Brian Selznick

Brian Selznick

Scholastic Press ($29.99)

by Roxanne Halpine Ward

Brian Selznick’s Caldecott Medal-winning book, The Invention of Hugo Cabret, employs illustrations and text to tell a story brimming with secrets and mysteries. In his newest book, Wonderstruck, Selznick again deftly pairs art and words, but in an even more complex and compelling tale of museums, silence, language, and family.

Wonderstruck’s protagonist, Ben, is a twelve-year-old boy in Minnesota whose mother recently died in an accident. After finding a strange locket and book among his mother’s things, Ben sets out for New York City to find the father he’s never known. In a parallel tale, the book also follows Rose, a young girl who runs away to New York fifty years before Ben does. The intersections of Ben’s and Rose’s experiences—and, eventually, their lives—become both fulfilling and surprising as they each seek answers on their journeys.

Selznick smartly uses the text to tell Ben’s story and the drawings to tell Rose’s, a technique that delineates the two plots while simultaneously emphasizing the experiences that Ben and Rose share during their adventures: arriving in New York, exploring the American Museum of Natural History, and weathering a severe thunderstorm. The two stories complement and play off each other, drawing Ben and Rose closer and closer together, until the text and art converge into one timeline and they finally meet.

Wonderstruck’s style is well suited to the subject matter, and Selznick does a masterful job of using form to reinforce the story: Rose is deaf, and as we follow her journey, the drawings capture the silence of her world. Ben, who has grown up hearing, is a natural storyteller for the text portion of the book, and he describes his world and his discoveries in vivid detail even as we glimpse the same settings through Rose’s eyes.

As deaf characters and culture are rarely represented in fiction, young adult or otherwise, the author is to be commended for his careful and nuanced presentation. The intertwining of the art and text adds layers of meaning to the story, making the characters’ deafness seem real and relatable. Ben, after losing his hearing, feels “swallowed” by the silence of his new deafness and struggles to come to terms with the change; Rose in 1927 learns that “talkies” are coming to her town’s movie theater, and what used to be her escape becomes one more way she feels lost and left behind by mainstream culture. Ben’s confusion and fear and Rose’s obvious dismay are perfectly paired. The deafness that both protagonists experience, and Selznick’s depiction of that deafness, makes the condition relevant to young readers.

Selznick’s exhaustive research continues to pay off not only in his work on deaf culture, but also in his presentation of museums, collecting, and cataloging. Ben is a collector at heart: he falls in love with space, plotting the stars in the Milky Way on his bedroom ceiling; learns all the different types of birds that live near his home; and keeps a treasured box full of items he’s found—a smooth rock, a bird skull, a turtle made of seashells. Rose keeps a scrapbook of clippings about a certain movie star and loves to build paper models of New York City’s buildings. The city is a place she dreams of visiting but can only gaze at from her bedroom window across the river, so her models allow her to “collect” the city though she’s forbidden to leave the house.

Other characters have collections, too. Ben’s mother, a librarian, catalogs books and collects inspirational quotes, and his new friend Jamie collects Polaroid photographs and secrets about the American Museum of Natural History. The Museum, with its impressive array of collections, becomes a focal point for both Ben and Rose; an exhibit on Cabinets of Wonders, the precursors to modern museums, attracts both protagonists and provides the book’s title. Selznick takes the classic adventure story of a child hiding in a museum and adds his own spin; young readers will be captivated as Ben and Rose each fall in love with the Museum and realize what their collections truly mean to them.

All these details are deftly connected through the intertwining text and art. Ben’s discovery of the book about the Cabinets of Wonders exhibit becomes a catalyst that leads him to New York, while Rose’s visit to the same exhibit in 1927 is one of the events that sparks her new life. When Ben eventually finds the exhibit, long since closed to the public, in a hidden room of the Museum, the earlier text descriptions from Ben’s book fit together with the illustrations of what Rose saw, and the whole room is familiar to the reader. Selznick capitalizes on even small themes: Ben’s love of the stars is mirrored in Rose’s reading of “star” magazines about Hollywood celebrities and in Selznick’s drawings of the sky.

It might be noted that Selznick falls short in developing his minor characters; Ben’s mother and Jamie are rendered well, but Ben’s and Rose’s other family members and Jamie’s father read like background props rather than real characters. However, Selznick more than makes up for this in his nuanced depiction of Ben and Rose. Young readers will find much to relate to as the protagonists struggle to be understood and risk everything in search of a true home and family. When Rose finds a giant meteorite in the Museum and learns that it was once a shooting star, she makes a wish on it, for somewhere she can belong. In the same way that a museum exhibit can fill its viewers with awe and wonder, Selznick reveals his characters’ deep emotion at discovering, after significant hardship and disability, a place where they belong.

Click here to purchase this book at your local independent bookstore

Rain Taxi Online Edition, Spring 2012 | © Rain Taxi, Inc. 2012