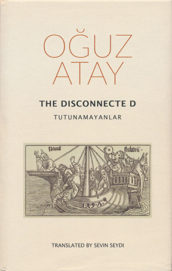

Oğuz Atay

Oğuz Atay

Translated by Sevin Seydi

Olric Press (£50)

by Jeff Bursey

The first thing to be said about The Disconnected (Tutunamayanlar in its original Turkish) is that it is available in a handsome limited edition, so the curious should contact the publisher quickly at the link noted above if they want a copy. The second thing is that it is considered of great importance in its homeland. In this novel, originally published in 1972, Oğuz Atay (1934-1977) brings together local literary concerns (i.e., the culture and languages of the Republic of Turkey as well as its predecessors), Russian literature (Ivan Goncharov's Oblomov is often cited, as are Chekov and Dostoyevsky), and 20th-century European fiction. Multiple and shifting points of view, time jumps, and the medley of modes, along with the underlying moodiness of the work emanating from its two main figures, Turgut Özben and his dead friend Selim Isık, mark this as a Modernist work.

This is its first translation into English. Translator Sevin Seydi started working on it as the original sheets came out of Atay's typewriter and discussed it with him. What she has produced is a narrative filled with tones—sombre, tender, brooding, puckish, malicious, defeated, constrained, bookish, melancholic—and the flow of feelings reflects how life is experienced rather than resembling a collection of set pieces devised by an author. It is far from a work of realism, for Turgut converses with the shade of Selim (it gives nothing away to say he committed suicide) whenever he thinks about him or encounters him in one of the many pieces of paper in his or someone else's possession. "Ah Selim, you have scattered your life away, left and right! These notebooks are all that remain." It is through apostrophe as a figure of speech—addressing the missing as if present—that the dynamic of their complex friendship is conveyed.

His sleuthing into Selim's past often ramps up Turgut's emotions—anger, grief, and depression, among others. This is tied to what may be a key item of this aspect of the novel: "to understand the meaning of life I need the meaning of death not to remain obscured." The pursuit to uncover the why of Selim's death helps Turgut come to some kind of terms with an inexplicable act while revealing how much he didn't know about his friend. Süleyman Kargı shows Turgut Selim's dreadful unpublished poem, "Yesterday, Today, Tomorrow," which is the subject of a lengthy analysis by Kargı. Here is a brief example of each: "Year nineteen thirty-six: known to but few. / To him, for sure, it's an important date." The explication of these lines tells us Selim's birth year, and that he "weighed five kilos and eight hundred grams exactly when he was born." This figure is regarded with suspicion by Kargı on the grounds that without a midwife or doctor around the weight could not be so accurately gauged unless someone placed the baby on the local butcher's scales. "That Müzeyyen Hanım [Selim's mother], well-known for her cleanliness should consent to this; that in a butcher's shop, among animals hanging from hooks, with flies all around them, Selim, on a cold autumn day, should be placed on a dirty balance, seems a very distant possibility to me." Mythopoeic exhalation and academic wheezing inflate poem and poet in a pastiche by Atay that courts the reader's patience even as it entertains, for few things in literature are as tiresome as ridiculous praise given to a flawed literary work by a thoroughly negligible figure. This section's abundant humour and outlandish conceits save the criticism, and the poem, from descending into sheer whimsy, though it's a close call.

That is not the only instance of narrative teetering between one mood and another. Each venue Turgut enters in search of his friend—homes, nightclubs, brothels, and bureaucracies—is a foray into the occasionally painful unknown by a character and also an opportunity for Atay to provide lists, transcripts, an 80-page unpunctuated section, mini-biographies, diary entries, the language of commercials—"All along the road our advertisements will keep you company"—and much else, ranging from the elegiac to the satirical. How does one accept this often humourous telling of a story that is replete with Turgut's grief? Are we to laugh or cry or scoff at the whole enterprise? Either you put The Disconnected aside as not enough (or too much) of one thing or another, or you tussle with its competing demands. One of Atay's most significant achievements is making this a book you can't read passively.

In the assumed world of the novel's events, from the first page Turgut finds it hard to tell his wife, Nermin, how inconsolable he is. Apart from the matter of his friend, he recognizes that that he can't discuss a crucial aspect of himself that most readers could identify with:

So am I going into this with the whole of myself, without even protecting 'it'? It, that 'thing', a little bit of himself that no one knew about; difficult to describe, but whose existence was very clear to him. Would he endanger that too? He had never surrendered the whole of Turgut. Never. He had kept it to himself. A 'thing', the value of which was known only to himself. Others too hide many things; even so, they may be left with nothing for themselves. This was different: if told it would have no value; therefore it could not be told. And even if you did give someone the 'thing', they would hardly notice it.

The struggle to keep hidden this mysterious "it"—an ineffable part of each of us scarce capable of definition in a way that would satisfy everyone—and the desire to speak of "it" is one more example of stress in the novel. Such seesawing instills a delicious tension in the reading experience, and it often seems like the perpetual motion behind the entire work.

A further stress, one that is political and historical, surrounds The Disconnected. The novel first appeared one year after the eruption of a bloodless military coup in Turkey that endured for some time. It is impossible to read this work—which brings together socialism and Marxism, European and Russian ideas, personal identity and the sadness of those who feel they don't fit in with their own society—without thinking of Turkey in the light of 2016's failed coup against its authoritarian president, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan. Selim, the disconnected of the novel, must have had numerous counterparts in real life for the work and its title to resonate so powerfully since it was first published, and as we read Atay now we can hardly remain blind to the disenfranchised, penalized, and arrested in contemporary Turkey.

Above I used the word "possession," and here it has a second important meaning. Everyone who has come into contact with Selim is haunted by him, and also wants to possess him. This is summarized by one member of the college cadre Selim and Turgut were part of when the topic of Selim's other friends comes up: "You went to the lady violinist's concert with this chap [a friend outside their group], didn't you? We would have embarrassed you, wouldn't we? We wouldn't have understood about B major . . . Only we here can be of any use to you." Turgut's encounters with other circles of friends eventually stop making him feel jealous or anxious. "We are not afraid any more . . . to hear what people have to say about Selim." When he reaches Anatolia, Selim's birthplace, he shares a cigarette with a peasant and thinks of his friend: "Was it to be your fate to be so alienated from one who makes his bread from the wheat sown by his own hands?" Fate, or social conditions, upbringing, poor spirits, tragedy; readers will arrive at their own judgments.

There is one last thing to mention about The Disconnected. The opening section, "The Beginning of the End," states the manuscript we are about to read was written by Turgut Özben and sent to an unnamed journalist (presumably Oğuz Atay) for publication. Then the "Publisher's Note" insists the events are "mere products of the imagination." This meta-device might seem to set the novel up as an extended joke, but, instead, amidst the humour The Disconnected is a mature consideration of grief's effects and a work that displays supple literary skill. We are fortunate to have it, finally, in English.