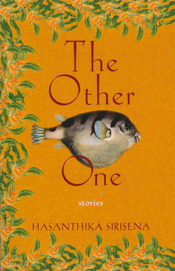

Hasanthika Sirisena

Hasanthika Sirisena

University of Massachusetts Press ($22.95)

by Jackie Trytten

In this debut collection of short stories, Hasanthika Sirisena presents characters in Sri Lanka and abroad in the aftermath of civil war, which seeps into many of their daily decisions and actions. Some families separate for economic reasons, and others learn it takes as much strength to stay as to go, all while trying to keep their identity wherever they live.

Sirisena’s characters are trying to fit in, to not be the other one—the one that is part of a minority, the one left out, or the one treated without respect or recognition. There is the one who finally allows her young son a Christmas tree, though they are Buddhist. There is one who converts to Christianity to help him advance his career in America, though he doesn’t believe in any religion. There are the ones who speak English to a lover because they don’t know the other’s language. In “The Chief Inspector’s Daughter,” two college students face their differences in language, upbringing, and the young man’s mistrust of her father and what he can do to people like him, a minority Tamil. In “War Wounds,” a woman’s younger brother, damaged by the war, becomes her responsibility and keeps her from joining her husband in Australia where he has found work. In “Third Country National,” a man works on an American military base in Kuwait after escaping an attack on a Sri Lankan army fort where he previously cooked.

Most of the characters in these stories don’t want to be the other one, but in the title story, Sebastian discovers he likes being considered one of the others. A cricket player who “grew up a Tamil and Christian in a country that had, still has, very little tolerance for either,” he realizes his South Asian teammates in North Carolina are respected by other teams for their skills; from the awareness that “cricket is also a great equalizer,” he learns acceptance and respect go both ways, and he invites an unlikely player, a Southern woman, to join his team.

Sebastian has other needs for cricket, too. “Cricket is my explanation. Cricket allows me to sit in a room of Sri Lankans and talk about something, other than pain and anger.” He is one character who finds a way through and past his history. “You see, for me, every tragic story is a story told in past tense: a recounting of sorrow done never to be undone. Every sports story, on the other hand, is, like all good love stories, a story told in present tense: when the ball twists and arcs and sails and dances, bobs and weaves, there is, in that second, a hundred different happy endings.” The stories in The Other One, which won the Juniper Prize for Fiction, convey tragic, sad, hopeful, and yes, sometimes happy endings.