photo by Eric J. Hermann

by Linda Lappin

John Domini’s work has been featured in Paris Review, The New York Times, and numerous other outlets. He is a versatile, genre-crossing author, and has published several books of nonfiction, fiction, and poetry over the course of his prolific career. The organizations that have honored his work include the National Endowment for the Arts and the Iowa Arts Council, and he has been an artist-in-residence multiple times with Italy’s Festival delle Storie. He currently lives in Des Moines, Iowa.

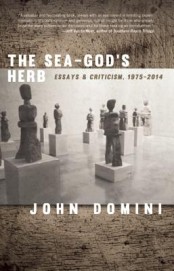

Domini’s new collection of critical essays, The Sea-God’s Herb (Dzanc Books, $15.95), sets out to celebrate and define post-modernism in the novel from a fiction writer’s point of view. It fills a gap in contemporary criticism, as essays and reviews of experimental American fiction are rare. The Sea-God’s Herb is a vast book, touching on many issues, and I was delighted to have the opportunity to discuss a few of them with the author.

Linda Lappin: Among the distinguishing characteristics of experimental fiction you mention is the writer’s willingness to breaks molds in terms of prose and structure. Surely the 1970s were a great era for iconoclasm in many areas of our culture, from politics to fashion and much else. What has happened to our mindset and our reading habits? Why are we afraid of the new and different when once we used to thrive on it? Or is that changing?

John Domini: The question suggests a monster squid, its home hidden, its arms everywhere. I mean that as a compliment, but I doubt I’ll manage to grab but one or two tentacles. I can say for starters that responsiveness to literary experiment doesn’t break down usefully into decades, but is better understood as a challenge that too many American critics have failed to meet for a good half-century now. That’s my argument in Sea-God, expressed both in my selection and, especially, in the lead essay, “Against the ‘Impossible to Explain.’” Over that same half-century, success in all the arts has been measured more and more oppressively by money and numbers. The hammer of Big Capital has come down hard; just ask any young American trying to make their mark in music. In music, though, even a corporate party like the Grammys will have room for work as outré as Beck’s. In theater, even Broadway will celebrate a mooncalf like Angels in America. U.S. publishing, however, and with it the established venues of literary criticism, still tends to hold the unconventional at arm’s length. Such a situation interferes with a willing reader’s appreciation of the rich adjustments storytelling has made to the sharp turns and sudden crevices of our times. In effect, it robs story of its continuing purpose: to steer us through those turns, and to bridge those crevices.

John Domini: The question suggests a monster squid, its home hidden, its arms everywhere. I mean that as a compliment, but I doubt I’ll manage to grab but one or two tentacles. I can say for starters that responsiveness to literary experiment doesn’t break down usefully into decades, but is better understood as a challenge that too many American critics have failed to meet for a good half-century now. That’s my argument in Sea-God, expressed both in my selection and, especially, in the lead essay, “Against the ‘Impossible to Explain.’” Over that same half-century, success in all the arts has been measured more and more oppressively by money and numbers. The hammer of Big Capital has come down hard; just ask any young American trying to make their mark in music. In music, though, even a corporate party like the Grammys will have room for work as outré as Beck’s. In theater, even Broadway will celebrate a mooncalf like Angels in America. U.S. publishing, however, and with it the established venues of literary criticism, still tends to hold the unconventional at arm’s length. Such a situation interferes with a willing reader’s appreciation of the rich adjustments storytelling has made to the sharp turns and sudden crevices of our times. In effect, it robs story of its continuing purpose: to steer us through those turns, and to bridge those crevices.

LL: Where would you situate your own fiction in the “New Republic of Long Narrative,” as you call the contemporary literary landscape? I was intrigued by your suggestion that postmodern experiments often “reveal their own devising.” Could you comment on that with regards to one of your own fiction projects?

JD: Ah, what writer doesn’t love this question? “Enough about those other guys; let’s talk about you!” I’ll try for restraint. For starters I’ll note that a lot of my own fiction isn’t so experimental as that of many folks I investigate in Sea-God. To mention just one, Carole Maso; her Aureole presents more of a challenge to conventional story and language than any of my novels and all but one or two of my shorter pieces. Okay, my Talking Heads: 77 includes the recurring “layout & pasteup,” pretty out there; the Naples novels too, Earthquake I.D. and A Tomb On the Periphery, occasionally poke up into a rarified atmosphere. Nonetheless, my fiction derives essential nutrients from social awareness; it generates drama from the history, the demographics, the economics. Nothing wrong with that; nothing you won’t find done better in, say, DeLillo’s The Names—and to point out such real-world concerns in DeLillo or Maso takes us back to the main argument of Sea-God, namely, that so-called experimental fiction isn’t in fact divorced from this trying experiment we call daily life. That said, I should add that just now, I’m po-mo in utero—in 2016, Dzanc will bring out my wildest yet, a story sequence titled Movieola!

LL: I loved your definition of your younger ’70s self as “Beat-besotted, Dylan-dreaming, Kafka-cantankerous, and Melville-megalomaniacal.” You were publishing reviews and other work back then in very prestigious places. What dreams did you have about the writer’s life, the writer’s role in community/society/academia or elsewhere—and how has it all panned out?

JD: I figured I’d be Vladimir Nabokov by now! Okay, joke, but isn’t that a fitting response to our fledgling dreams? As for how it’s panned out—it’s a letdown, inevitably, though my ups and downs are pretty typical: economic and romantic crises, editors and others who sometimes lent a hand and sometimes slapped me down. I guess what I find most interesting about your question is the hybrid construction “community/society/academia.” I did have such a thing in mind when I was starting out, and I did conceive of criticism as a way I could help raise a roof-beam or put down a decent road for all of us sensitive to fiction’s changing shapes. I perceived such a program for myself, and I’ve stuck with it since. So there’s that.

LL: I was a bit taken back by a comment you make about fiction by American women writers: “Fiction about a woman’s place in the world has tended to omit the spiritual, the Unknowable.” That’s an interesting perception, which I don’t personally share; it suggests that women writers tend to see the novel as springing from social rather than spiritual concerns. In your view, why is this so?

JD: Ow. Can I claim context, here? That line is in a long essay about a woman writer, Jaimy Gordon—an essay trying, among other things, to win her a wider readership. Around the statement there are other factors in play, like Gordon’s age and generation, plus of course the argument of my book as a whole. And while I’m getting all blustery and defensive, I’ll add that the editors and I made changes in order to include more women; we didn’t want a Boys Club. Okay. But I appreciate the question; it means my Sea-God has initiated a conversation, even if the give and take pains me a bit. It means I’ve contributed a bit to that community etc. I just mentioned, by raising such questions. As for your more provocative notion re: women’s fiction “springing from social rather than spiritual concerns,” I suppose that could be taken as an implication in the Gordon essay. I’d be leery of such a sweeping pronunciamento, myself, but maybe my book isn’t. In any case the argument seems to call for—yes!—another essay. Someone ought to raise the banner of, say, Sylvia Plath, and under it lead the Anti-Dominians out to battle. I only hope I live to see it.

LL: Not very many women writers are mentioned in your book, and in fact, there just aren’t that many contemporary experimental women writers that have achieved national recognition. There could be very many different reasons for that. One thing that came to my mind, with regards to my initial question, is that many innovative women writers privilege one or the other (Arundhati Roy, for example, or Anais Nin), structure or prose, but not both at the same time, which would place them outside the camp as you define it. Do women writers tend to be more conservative? Is it harder for a woman to affirm herself as an experimental writer? Do publishers tend to take more seriously male experimental writers than female?

JD: My previous answer touched on this subject. The editors and I cared about including women, though of course we were limited to what I’d published. I didn’t have anything on Aimee Bender, for instance, and her fabulism would’ve felt at home. What’s more, since the book appeared, I’ve written on iconoclastic texts by women like Jenny Erpenbeck, books that would address your concern. Still, this question brings up a larger issue, namely, how commercial publishers tend to view outside-the-box stories and novels from women—which is askance at best. Again, we can all think of exceptions, but insofar as Sea-God calls mainstream American editors and reviewers to task for their aversion to risk-taking, the complaint also applies to how they’ve treated women writers. Not long ago I heard Carole Maso open up, with admirable frankness, about the difficulty she still has getting published. What does that tell you?

LL: You conclude with an essay on Dante and the archetypal storytelling patterns we find buried in narratives. Could you say something about your own relationship to Italian classics and how they have influenced your own fiction?

JD: First, I ought to point out that one critic has already claimed the Dante essay feels shoehorned in. It just won’t fit, says he, and the God—or Goddess—of lit-crit may agree. If so, all this mere mortal can do is reiterate the point made in the preface, namely that the essay belongs both for its unearthing a less than obvious narrative in the poem, and for how it connects that strange narrative to our ordinary cares and joys. Like all the other pieces in Sea-God, it argues for the humanity of challenging literature. Now, in my mind’s eye and ear, that very claim sounds Italian. Even at its most baroque, so highly wrought as to seem solely about itself, Italian work has always conveyed something of the street, garden, kitchen, and, of course, the bedroom. Even the infinitely brainy Da Vinci reveals, in his Madonnas and saints, that he knows suffering and passions, and asserts their centrality in his art. I could work up a whole new essay, one that explained, also, how I’m holding off on the Naples trilogy of Elena Ferrante, until I can take a good long run at her work in Italian. Still, once more I’ll rein myself in, and mention just one figure who’s lately meant a lot to me: Eduardo De Filippo, the masterful Neapolitan playwright (and more, of course). Every time I’m in southern Italy, it seems, I’m bowled over by yet another of his plays. The one Americans might’ve heard of is These Ghosts (1946), which John Turturro brought to Broadway. No one who sees it can go on believing that the Latin Americans invented magical realism—or that something groundbreaking formally can’t also prove heartbreaking.