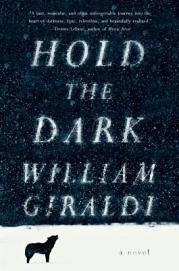

William Giraldi

William Giraldi

Liveright Publishing ($24.95)

by John Pistelli

To date, the novelist William Giraldi is less renowned for his fiction than for his criticism. With his notorious 2012 review of Alix Ohlin’s work in The New York Times, Giraldi entered the literary scene as a fiery, uncompromising defender of canonical standards on the model of one of his avowed heroes, Harold Bloom:

There are two species of novelist: one writes as if the world is a known locale that requires dutiful reporting, the other as if the world has yet to be made. The former enjoys the complacency of the au courant and the lassitude of at-hand language, while the latter believes with Thoreau that “this world is but canvas to our imaginations,” that the only worthy assertion of imagination occurs by way of linguistic originality wed to intellect and emotional verity. [The New York Times, August 17, 2012]

Giraldi’s approach proved largely unwelcome, with various literary websites and magazines calling him everything from “horrifyingly aggressive” to simply “dickish.” But despite its violation of the literary world’s sometimes cringing Internet-era commitment to empathy and relativism, the aestheticist position defended by Giraldi has much to recommend it. For critics like Giraldi—and for the likes of Bloom and Wilde before him—works of art and literature are emphatic ideals standing above and against death-tending nature: a poem or a novel is “a lie against time,” in Bloom’s phrase, a willed assertion of sensibility in the face of our inevitable finitude and vulnerability. On this view, the library of great books is less a temple than a gauntlet: past masterpieces provide examples of the imagination’s power even as they set a chastening measure for future works. To deny this, according to the aesthete, is to acquiesce to death-in-life.

Contemporary writers therefore need to know their tradition if they are to go beyond it; otherwise, they may merely emit banal effusions in an attempt at unmediated self-expression, unaware that they are creating little more than lifeless travesties of bygone aesthetic vanguards, like the emotive free verse of the proverbial adolescent poet. If this were not so—if tradition and standards were unimportant—then writers from previously-excluded social groups would not have expended so much energy throughout the last century in charting those groups’ own distinct literary traditions, with critical landmarks from Virginia Woolf’s A Room of One’s Own to Edward W. Said’s Culture and Imperialism.

Do Giraldi’s own novels succeed on these forbiddingly canonical terms? His 2011 debut, Busy Monsters, does not quite. An absurdist picaresque about the too-aptly-named Charles Homar’s search for a fiancée who has left him to hunt a giant squid, Busy Monsters too often comes off as a series of farcical linguistic effects, a barrage of big comedy. Two things rescue it from excessive zaniness. First is Giraldi’s sophisticated ability to create in Homar—if not in his other figures—a nuanced character who wins our sympathy not in spite but because of the vulnerability implied by his otherwise ridiculous naïveté and dangerous attraction to violence. An authentically Cervantine pathos arises from Homar’s self-defeating attempts to do good in a world determined, at least until the end, to thwart him.

Busy Monsters’s second virtue is precisely its conscious relation to the long history of the novel and not only to its proximate influences in the huge-voiced and hugely flawed narrators of Saul Bellow or Barry Hannah. Homar narrates his escapades as ongoing installments in a monthly magazine column; this means that, within the novel’s fictional world, the characters have read and commented on the previous installments, which affects the writing of future ones. With this trope of narrative as an unreliable and perpetually processual text, Giraldi returns us to the origins of the European novel in such metafictional romps as Don Quixote and Tristram Shandy, forcing us to confront the often absurd mediation of language in the construction of narrative and identity as Giraldi’s characters comment on the novel in progress: “He admitted that my memoirs ‘Witchy Woman’ and ‘Them Prison Blues’ were cheap on details, not nearly as thorough as they could have been were I blessed with quote Jamesian interiority and the plotting proficiency of Wilkie Collins unquote.” But criticizing one’s own book in one’s own book, however amusingly or with whatever learned appeal to literary history, seems like a bit of a cheat; a writer as ambitious as Giraldi can’t play forever without a net.

Giraldi’s new novel, Hold the Dark, is fortunately a major advance on Busy Monsters. The first novel’s essential elements—the fleeing woman, the voyaging man, the beast as quest-object, the human capacity for violence—are recombined in the second to produce not comedy but tragedy, not absurdism but a visionary gnosticism that pictures humanity as absolutely alienated within nature.

Set in an isolated Alaskan town, Hold the Dark opens with a sentence suggestive of folklore: “The wolves came down from the hills and took the children of Keelut.” When Medora Slone’s boy is taken, she calls in the aging wolf expert Russell Core to help her track down the boy’s bones and slaughter the wolf that killed him. Core, with little in his life since a stroke incapacitated his wife, decides to go to Keelut and help Medora. Core is thus the reader’s surrogate in the icebound north, an emissary from the disenchanted world of reason: “They’re just hungry wolves, Mrs. Slone,’” he explains, “‘It’s no myth. It’s just hunger. No one’s cursed. Wolves will take kids if they need to. This is simple biology here. Simple nature.”

Core learns quickly enough that events more extreme than reason can explain have transpired in Keelut, and that the mysteries of human motivation are more frightening than the hunger of wolves. It turns out that Medora has herself killed her son. When her husband, Vernon, who has just returned from fighting overseas, sets off in pursuit of her, Core decides to follow. Vernon, accompanied by his childhood friend, Cheeon, begins a killing spree across the Alaskan wilderness as he searches for his wife, whom a wise old villager claims is “possessed by a wolf demon.”

At times, Hold the Dark seems like a polemical response to trends in contemporary literature, implicitly judging social realism to be an evasion of the reality that “man belongs neither in civilization nor nature—because we are aberrations between two states of being,” even as the novel’s refusal to explain fully its supernal elements (is Medora really cursed or possessed?) underscores the crude literalism in the fantastical genres with their eminently reasonable “world-building.”

The novel alternates between the perspectives of multiple characters, but its third-person narration attempts to create a consistent and singular idiom. Like such precursors as William Faulkner, Cormac McCarthy, and Daniel Woodrell, Giraldi seeks a higher verbal register than the vernacular clarity of realist prose. Though set in the present day, Hold the Dark’s language is jeweled with archaisms—unbidden, ebon, sere, weal—along with phrases from Gerard Manley Hopkins and Wallace Stevens.

But as in Busy Monsters, Giraldi boldly places his work in an even longer and more demanding lineage. Its promotional copy describes Hold the Dark as “an Alaskan Oresteia,” and while this sounds like nothing more than bombastic overkill from the marketing department, it is not entirely wrong. Giraldi has brought the ethos of Greek tragedy into a contemporary setting; the drama evoked by Hold the Dark is not Aeschylus’s trilogy, however, but Euripides’s Bacchae. Like that play, the novel shows a community wracked by a visitation of ecstatic violence, and a self-styled man of reason and moderation trying to hold his world together, only to be drawn into the chaos. Giraldi, like Euripides, suggests that it is vain to resist these periodic outbreaks of frenzy, because they come from beyond the rational world humans have built and are thus beyond that world’s control. Hold the Dark’s terse and aphoristic dialogue at its best has the compressed intensity of Euripides’s drama, especially as conveyed by Anne Carson’s recent translations: “Why is this happening to me, Mr. Core? What myth has come true in my house?”

In an essay on The Bacchae written in 2011 for the Tin House blog, Giraldi concludes: “Dionysus will not be beaten back, cannot be buried in our dullness. He is our nature, our blood. So get up and dance.” Hence the ambiguity in the novel’s title: at first we think Giraldi is counseling us to hold off the dark. But what if we ought to embrace it instead? This question brings us back to where we started: with Giraldi’s defense of literary tradition as a necessary curriculum for the ambitious writer. Literature is the gathered testimony of men and women driven by the daemon, wolf or wine-god, to set down their ecstatic visions before the dark claims them absolutely. With Hold the Dark, Giraldi has added his voice to the tragic chorus.