By Brice Brown

Illustrated by Ahndraya Parlato

In 1891, after nearly thirteen years of construction and seemingly endless modifications, Hudson River School painter Frederic Edwin Church’s 250-acre Persian-fantasy estate, Olana, was finally completed. From the very beginning, Church conceived and composed Olana as if it were one of his paintings, designing ornamental stencils and furniture, selecting a precise color scheme, carefully overseeing the acquisition of every decorative object, and orchestrating the surrounding landscape into controlled vistas. Though he worked closely with famed architect Calvert Vaux, Church controlled every detail of every decision. It is, in fact, as if the whole of Olana oozed off one of Church’s own canvases into existence; it now stands as his final masterpiece, a self-contained, individual work of art on equal ground with the rest of his artistic output.

Much like Olana, poet John Ashbery’s domestic environments—consisting of his house in Hudson, New York, and his apartment in the Chelsea neighborhood of New York City—are stand-alone works of art conceived and composed with the same level of conscious artistry that informs his poetry. For Ashbery, the domestic urge, the operation of homebuilding, operates in tandem with the work that is conventionally recognized as his creative output. An understanding of the one thereby becomes essential to an understanding of the other. Time and place, however porous, are crucial elements in Ashbery's writing. His domestic environment is an organic, mutable living-quarters-cum-laboratory where all decisions—such as adding or removing objects from the space—are ministrations to the creative process.

It’s a safe bet that any symposium on Ashbery’s habitats will focus on his Colonial Revival house in Hudson, New York. Deservedly so, for of his two residences, the Hudson house is not only gorgeous in its architecture and interior design, but it offers a more complete statement of the overall Created Spaces concept. Hudson represents only half the equation, however. The Chelsea apartment's strange silence is counterweight to Hudson’s histrionics. And because it is often overlooked, because in many ways it requires a greater intellectual leap of faith, and because its deceptively understated appearance speaks volumes, the particularities of the Chelsea space as a facilitator of Ashbery’s poetry—and, importantly, as the setting for his daily life—warrant a closer look.

Some facts: In 1972, John Ashbery moved into a tall, post-war building on the edges of the Chelsea neighborhood in Manhattan. But this first apartment was not to be his final destination within this building, for two years later, in 1974, he moved to a unit on a higher floor, located in the rear. Then, in 1984, when a spacious three-bedroom apartment on an even higher floor became available—with sun-blasted east, south, and west exposures—he jumped at the opportunity. This has been Ashbery’s residence ever since. In his apartment-hopping, Ashbery seems to have been in pursuit of a pre-envisioned ideal. On taking possession of his current New York City residence and, almost simultaneously, his home in Hudson, he began the process of expanding and refining his unified, lived artwork of environment. David Kermani makes a persuasive argument that Ashbery’s initial move into the Chelsea building signified the birth of his entire Created Spaces project, and the resulting residential upgrades—including the purchase of his Hudson home in 1978—were expansions and refinements of the overall artwork that has become his Created Space.

Chelsea is less on display than Hudson, and therefore the collection of objects and their arrangements feel more offhand and relaxed. Because of this abundant casualness, Chelsea has an organic, unstructured feel. Though much smaller than Hudson in terms of square footage (and therefore, arguably, by default more intimate) the general sensation is one of airiness and openness: the projection seems to be always external, out toward the city instead of in toward constructed vignettes. What would seem the most obvious distinction between these two dwellings, namely the urban/rural divide, is not exactly accurate, or at least this is not how Ashbery sees their main difference. For him, the split is between youth and maturity. The interiors and objects in Hudson are predicated around his nostalgia for childhood, while the unfussy, workaday aesthetic of Chelsea embodies Ashbery’s model for the adult life.

On first encounter, Ashbery’s Chelsea apartment might strike a guest as ordinary, mundane, almost disappointing. This feeling of confused disenchantment could be compounded when considering how Ashbery has transformed the Hudson residence into such a grandiose, multifaceted work of art, firing narrative, theatric, cinematic, and musical pistons at full steam. The Chelsea apartment is just a quiet whisper by comparison. And though the initial impression of Chelsea might be unexpected, its utter commonness should come as no surprise from the poet renowned for his ability to flout received or preconceived notions. For it is this very idea of the commonplace—of the beauty found in the nuanced layers of banality and a John Cage-like openness to the symphony of the everyday—that transforms time spent in Chelsea into the experience of experience. Beneath this blanket of bland familiarity, Ashbery encourages a recognition of the dullness underlying our own lives: only when we accept this fact can we truly see and appreciate the subtler, more rewarding aspects of getting on with the day to day.

Moving from room to room in the Chelsea apartment feels like a conversation, or maybe a casual handshake. Paintings by artists such as Jane Freilicher, Alex Katz, Leland Bell, and Trevor Winkfield mingle with postcards of influential works such as Parmigianino’s “Self-Portrait in a Convex Mirror,” a Popeye head poking out of a can of spinach, small toy trees, a collection of light-reflecting clear glass, and a wide mix of furniture styles, including a lovely Biedermeier sleigh bed. Other oddball objects and ephemera, like a Mexican Day of the Dead figurine, pop up—no, they don’t pop as much as creep—to give pause, to force a mental gear shift, and to act as reminders that alternate, even infinite, interpretations exist for any experience of a place.

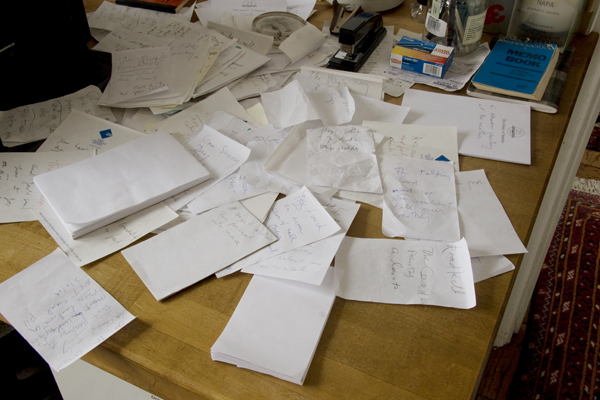

Stacks of books and piles of paper reveal a life lived in the world of letters, and add a glaze of disarray to the entire scene; they also transform language’s bodiless existence into physical fact, composing miniature landscapes throughout the apartment. A collection of early nineteenth-century French puzzle-plates dotting a few of the apartment’s walls are quirky amalgams of text and image, like glyphs representing the fruitful tension between the language of image and the language of words: some of the plates incorporate a complex mash-up of phrases, pictures, musical staffs, and numbers to relay some type of saying, or perhaps a verse of poetry; others feature collages of mini-tableaux intended to transmute image into narrative.

The dominant feature of the apartment is a large west-facing picture window. The apartment’s location on a high floor not only means that the views are, for now, unobstructed all the way to the Hudson River, but also that light is allowed to pour in unobstructed, casting an eerily homogenizing layer of luminosity over the furniture, objects and artwork inside. The glass feels like a permeable membrane, the site where a comfortable truce is achieved between the constant, unpredictable flux of life taking place outside—sunrise, sunset, weather, traffic, gentrification, love, death—and the controlled experience Ashbery mediates inside. The window’s dimensions roughly approximate an oversized flat-screen television, lending the passing of time witnessed on its glass surface a cinematic, second-hand quality. Strategically placed to face the window is an armchair where Ashbery undoubtedly spends a good deal of his time gazing. But this chair is more than comfortable furniture, it is the apartment’s sweet spot, the precise location to best experience the overarching themes girding Ashbery’s created space. Here, sitting in this chair, everything comes together, hums with purpose, and unfolds into a mesmerizing temporal and spatial performance. And this performance begins to reveal the nuanced mysteries to be found in the run-of-the mill, not-so special, totally common—yet universal—details of everyday life.

What is the value of thinking about an artist’s dwelling or environment in relation to his work? Is this an archaeological inquiry? Will the study of Ashbery's scraps of paper, pairs of shoes, tables, dinner plates, or knickknacks deepen our understanding of his work? Does an examination of Ashbery’s domestic life and environment—composed of personal moments and places that Ashbery has never intended to share with the public, which he may himself not consider to be parallel to his writing—simply add up to biography?

In Ashbery's case, the desire to peek inside his residences, to examine the details of the rooms, their layout, and the various objects inhabiting them, is legitimate. His poetry and prose are intimately entwined with his domestic environments. Ashbery’s work is permeated with references to domesticity and a sense of place, with nostalgic memories reflecting on or provoked by interiors, and with oblique architectural notations. His impulse to collect and to deploy a textual mash-up of idioms, dialects, and phrases is mirrored in his role as domestic curator, orchestrating the myriad objects in his living spaces into quirky narrative vignettes or meticulously balanced installations. Here’s a telling detail: in the process of organizing this symposium, Micaela Morrissette compiled a listing of references to basements, windows, furnishings, homes, apartments, buildings, etc., found in Ashbery’s poetry. This document, not nearly exhaustive, totals 86 pages.

Let’s be honest: we all have that voyeuristic itch which needs to be scratched on occasion. And judging by the numerous examples of preserved artists’ residences and studios around the world—some even having been turned into popular public museums—it seems we are unflaggingly fascinated by the ways creative people live out their everyday existences. Does the allure of everyday domesticity spring from our desire to understand our own habits in this way, as a vestige of our own creativity rather than as the dreary reality of our day-to-day grind? Or maybe the domestic habitat appeals to us because, in its humanity, it emphasizes the status of the artist as an exemplification of the dreams and expression common and essential to our civilization as it progresses through time. It’s anybody’s guess, and regardless of the answer, it’s a titillating and utterly humanizing moment to stand in the presence of, say, Mozart’s kitchenware.

Joseph Cornell gathers ordinary, seemingly unrelated items together so that chance associations can generate metaphorically rich ideas about the enigma of the ordinary object. In a similar way, the contents of Ashbery’s Chelsea apartment render the familiar strange, twitching the veil that hides the mystery behind the banal or the evident. The poetry, the curatorship, the act of imagination is concentrated not in a final, frozen, formal assemblage, but in the act of selecting, arranging, pairing, isolating, or seeing. Ashbery’s choices regarding acquisition and display—of both the language in his poetry and the objects in his apartment—are anything but random. Nonetheless, in both his textual and environmental constructs prevails a free-flowing quality, an offhandedness that offsets any overarching strategy. The whole affair has the weird yet thrilling feeling of being minutely specific and dispassionately general at the same time. As in Ashbery’s poetry, the visitor is invited to make the connections, to unearth possible meanings and narratives from the raw materials provided. Of course, the irony is that Ashbery’s scenario of potentially endless conclusions will forever be an open work, producing the nagging feeling that there is really nothing to “get” in the end. This very inconclusiveness is thoroughly beguiling, hinting that, as Ashbery has said, the “tension is in the concept, not in the execution.”