by Rosanne Wasserman

Illustrated by Ahndraya Parlato

Foreword, March 2008

Fifteen years ago, when John Ashbery and I walked at snail’s pace around his house to prepare this article, he was still in the process of fashioning his surroundings; he has not ceased to create and recreate them in the intervening decade and a half. Not surprisingly, then, the article describes only one stage in the evolution of his house, some rooms of which have, since then, been further embellished, or reimagined, or pulled apart and are still being put together.

Changes both major and minor have altered these rooms described below. In the Music Room, sparkle has been provided aplenty by the addition of an enormous antique strung-crystal basket-style chandelier. Some paintings, like the white rose by Alex Katz, are no longer on the walls where they were: they are traveling, on loan to various shows at museums or galleries, or they have been replaced by different pieces, as the poet’s taste has changed or sought refreshment. Notable, for example, is a large black-and-white seascape photograph by Lynn Davis, on the wall where the white rose hung. A collection of poetry books has migrated from bedroom to parlor; the toys on the coffee tables are not the same. Some paintings that were in upstairs closets then are on the walls now; the closet stores other canvases at present. (Some of the painters, too, have traveled on: Larry Rivers passed away in 2002; R. B. Kitaj in 2007.)

A significant omission in this article is any discussion of the cellar, which has the usual laundry and furnace rooms, an extra freezer, and another bathroom, as well as two busy offices, files, and archives. In 1993, still more archives were shelved in the unfinished, high-roofed main room of the attic, and since that time, Flow Chart Foundation archives have been stored in an additional space elsewhere in Hudson.

Also omitted below are some important dates: foremost is 1983, not the year in which John purchased the house (he bought it in December 1978), but the date that David Kermani gives as when the house began to become a home, with renovations underway. Five years later, John and David with great generosity offered temporary lodgings to my husband, Eugene Richie, and myself, while we were renovating our own house, an A. J. Downing-style cottage a mile away, a task that took the better parts of 1987–90.

Although an old home requires constant maintenance and repair, so that workmen still come and go, John was just developing his ideas for the house at that time. The process of creating the space was in full sail during the years we were there, and indeed continued right through and past the 1993 tour. However, although some significant acquisitions came much later—the Music Room chandelier being primary among these—nevertheless, by 1993, the interior was recognizably what it is today. (This chandelier and a number of other works and scenes discussed below appear in illustrations accompanying articles by Stephen Sartarelli, “Art of the Poet”1; Dinitia Smith, “Poem Alone”2; and Brice Brown, “Any Interpretation Will Do.”3) These years also saw the writing and publication of A Wave, April Galleons, and Flow Chart, books that I think of as moved by the same muses with whom and for whom John was designing the spaces of his home. His later books, by contrast, seem more to reflect on these spaces, live within them, and rest inside the finished work.

Living at John’s was a splendid treat and an inspiration in those years before our son, Joseph, was born and I began to teach full time. I wrote many poems about or including elements of the house, and was not alone in doing that—many poets and artists who were guests in Hudson found themselves equally moved to write, record, and respond to his gorgeous and idiosyncratic spaces. One of the most beautiful works inspired by the house has been the composer Robin Holloway’s Violin Concerto, Opus 70. When someone once complimented John on this effect, he grinned and troped Falstaff—“I am not only poetic in myself, but the cause that poetry is in other men!” As Ann Lauterbach has written, “His greatness has allowed many poets—from David Lehman to, say, Charles Bernstein, to name two not quite at random—to explore the territory he opened.”4 She’s discussing literary territory, but the metaphor reverts neatly to the actual interiors of his home. For my own part, after many years working as an editor of art and exhibition catalogues at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, I found John’s house a perfect antidote for what I like least about museums: that they are not lived-in spaces. John’s house, filled with objets d’art and arranged into subtle, funny, and magnificent scenarios, is also always a place where people live and visit, sleep and dine, watch TV, wash up dishes, sit in chairs. Long may they do so.

When the poet John Ashbery saw the opportunity to purchase a grand old Victorian townhouse upstate in the Hudson Valley, he entered upon what was, for him and his temperament, a very special pursuit. For over a decade, he then worked at restoring, redecorating, and enriching this already beautifully constructed and well-preserved building, creating for himself a space as marvelous as the best of his poetry. This house and its furnishings—like Frederic Church’s Olana just a few miles away above the Hudson River—are a masterwork of visual imagination, revealing not just the personality but the muse of its artist-owner. In a review of Hotel Lautréamont, Michael Wood suggests that Ashbery’s poetry often parodies “the generic voice of a moment or manner in earlier poetry.” Wood writes:

The tone of these allusions is far from that of a solemn adherent to a great tradition, a poet daunted by the lateness that so interests Harold Bloom; more like that of a brilliant and naughty child in an attic full of toys. Or an inquisitive adult in a bazaar crowded with beautiful, battered, and improbable objects.5

Wood’s similes are in fact a fair literal description of the spirit of Ashbery’s interiors.

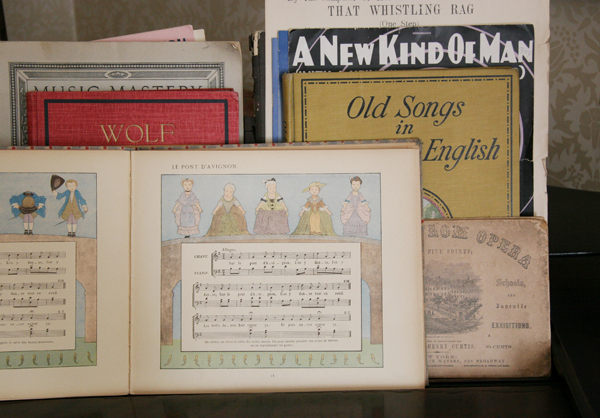

The Classical Revival town house was built in 1894, and is a model example of late Victorian architecture and decor, with intricate woodworking, stained glass, and built-in shelves and cupboards. Ashbery has filled its fifteen rooms with paintings and prints by artists he knows and loves; with collectible and rare objects of pottery, glass, metal, porcelain; with books reflecting his influences and enthusiasms; and with, to lift a list from Rimbaud, “door panels, stage sets, back-drops for acrobats, signs, popular engravings, old-fashioned literature, church Latin, erotic books with bad spelling, novels of our grandmothers, fairy tales, little books from childhood, old operas, ridiculous refrains, naïve rhythms,”6 and B-movie video cassettes. Moreover, to quote Ashbery himself, “There are a lot of other things of the same quality / as those I’ve mentioned.”7

More than fifty paintings or works on paper are framed on the walls, along with posters, lithographs, pages cut from old magazines, photographs, and other graphics. Each room has a variety of objects and themes so dense and yet so magically right that their individual atmospheres seem almost human; they have not so much been decorated by, as possessed by the spirit of the master of the house. Ashbery once mentioned to me that his arrangements of objects follow various dramas in his imagination: in part a re-creation of his grandparents’ home in Rochester, New York, where he spent much of his childhood; and in part an idea of what might exist in each room, in some dreamed-up family, as if he were designing a stage set, a giant dollhouse, or a gargantuan Cornell box. For more about his grandparents’ home, the poet’s own words are best consulted, in an article from Architectural Digest, which also features many images of the house circa 1994.8

In 1993, the poet and I walked together through the work-in-progress of his habitat; I invite you now to tour this wonderful house with John Ashbery and me, room by room, to see the paintings and prints on the walls, as well as a few of the other remarkable objects gathered there. Ashbery kindly showed me all around the house, identifying and commenting on the things we saw; I will relay to you what he told me. Since I am not an art historian, I cannot offer an exact descriptive catalogue; I will instead describe both what caught my eye and what Ashbery thought worth mentioning.

There are two main floors to visit, with a brief look up to the attic. On the first floor is a large front hall, with a music room to the left, a library to the right. Off the back of the hall is a dining room, from which a left door leads to the butler’s pantry, then into the kitchen. A grand front staircase from the hall leads upstairs, as does a narrower back stair from the kitchen. A central hall upstairs opens onto six main areas: the upstairs sitting room, a second upstairs library, the master bedroom and its screened sleeping porch overlooking the garden, a guest bedroom, and the bathroom. Between the guest bedroom and the upstairs sitting room is a small but sunny study. The sixth door leads to the attic, where an attic room is also furnished for guests.

The front hall is preceded by a small foyer just past the outside doors with their great curling hinges. The alcove is floored with unglazed gray and white ceramic tiles. Between foyer and front hall is a brilliant wall of uncolored, leaded glasswork and oak wainscotings; the inner doors, too, are set with leaded clear-glass windows, with a spoked-oval spiderweb design of the sort so popular in Gothic cinema. A small Persian star-shaped ceiling lamp set with colored glass bosses hangs above. On the left are two large ceramic umbrella-stands with oriental dragon motifs; on the right, a small gilded rush-bottom chair, very squarely built but delicate-looking. It seems to say, “If you must sit down on me to take off your boots, go ahead; but don’t sit down too hard.”

After the grisailles of the foyer, the dark, richly colored front hall comes as a sumptuous surprise. The hall is magnificent with carved wood details: oak panel wainscoting, inlaid woods on the floors, carvings on the ceiling, great sliding doors off to the left and right, an ornate gilded chandelier, a grand staircase curving into the room at right, a fireplace and big mirror at the back, which reflects the foyer’s glasswork as you leave it and progress into the house. The mantel before it holds a brass clock and two Royal Teplitz porcelain candelabra figurines, shepherd and shepherdess, which Ashbery inherited from his grandparents. All of these details are usually lit only by colored sun falling from the monumental stained-glass window at the top of the first landing of the staircase, so the room is dark and glittery like an Arabian treasure cave. The Persian carpets on the floor show the concern of Ashbery’s friend David Kermani; it is also Kermani who creates and tends to the mammoth Christmas trees, covered with antique glass ornaments from his collection, which illuminate and enchant the back of this hall for a good part of the year.

The hall’s art is primarily oriental, larger and smaller prints and paintings not brightly lit, but of clear figurative designs that make their statements from the comparative dimness of the hall, or blend quietly into the shadows until studied, when they suddenly surprise the watcher: that wall’s full of life! There are a number of Chinese landscape scrolls: one of monkeys, three of birds: these are machine-made textiles. Smaller Japanese prints are grouped together on the left wall: first, a Hokusai design of moon and cherry blossoms in black and white; with it, a very blue blue jay among some very orange leaves. At the back of the hall, a three-part print tells some tale of a tempest, a demon on a rope, and a dancer with a fan under a parasol. This print oddly foreshadows the large Kitaj in the music room next door.

Photo by Ahndraya Parlato.

The music room at the left of the foyer is full of a steady but not sparkling light, its fireplace and mantle painted white, with an oval mirror built in above. The room gives the impression of a small manmade lake, not because there is anything blue or skylike in it, but because of its stillness, order, and light. The mantle features a replica of a Jean-Antoine Houdon terracotta bust of a child; on a side table is an original, a 1775 terracotta of a young lady by Phillipe-Laurent Roland. The eighteenth-century French motif is repeated with marble-topped tables, inset with porcelain plaques; gilded chairs and sofa; two side mirrors; and the two front windows with a gilded mirror in between. American details include a small brass reading lamp shaded by a Steuben glass creation called “Aurene”; a hand-painted glass landscape shade enhances another side-table lamp. But the Surrealists have been here, as well, with a little playful trompe l’oeil: two ashtrays seem to hold a pipe or a nutcracker and nuts: all are of porcelain. A potted ficus tree and a grand piano draped with a red paisley shawl complete the scene.

Six large works hang on these walls. The eye is seized first by a very big genre scene, full of colorful figures, action, and violence: Susan Dakin’s painting of an assassination attempt on a general, an episode from the 1929 Mexican novel of political intrigue and corruption, La Sombra del Caudillo by Martin Luis Guzman. The wounded leader lies on the floor of a posh restaurant, behind an overturned table, his napkin still in his collar, bloodstains on his uniform, a gun in its holster at his hip; he is surrounded by the dark, concerned faces of his staff and attendants, some of whom have apprehended the gunman as he tried to flee out the restaurant’s windowed street doors in the background. Food, flowers, and blue seltzer bottles spill around in the foreground. The New World revolutionary mood of the entire piece suggests that a window from the future has opened into this eighteenth-century room; or perhaps it’s the door of a time machine from which we visitors have just tumbled.

After this canvas, the others seem quieter, deeper, even the Willem de Kooning, a calligraphic black-and-white silkscreen dated 1970. The print is numbered 27/28. Its abstract but violent squiggles recall Japanese sumi, especially after the orientalism of the hall. This work is one of the series Ashbery reviewed during his decade-long Paris sojourn, while writing for the Herald Tribune.9 Even quieter, on the opposite wall, is a huge white rose on a burgundy background, its petals highlighted with gray and yellow. I always think of Georgia O’Keefe at first sight of this painting, but it’s an early Alex Katz, 1966, not his familiar human figures, but with his recognizable, simply stated two-dimensionality.

With these works hangs a portrait, in subdued but clear colors, of the poet as a young man: “John Ashbery” by Fairfield Porter, from the painter’s Southampton home in 1957. The poet wears a blue short-sleeve shirt and tan slacks with a brown belt; he turns the left profile as he sits in a studio chair. (The image was reproduced in 2004 on the cover of Ashbery’s Selected Prose.) Another portrait hangs by the piano: “Eduard,” the head of a man from a series painted in 1943 by Jean Hélion. This abstract bust wears a black-banded fedora; his red tie is the only bright color in a gray palette; the face is reminiscent of a Léger. Painted during his American period, it shows the qualities Ashbery lists in “Jean Hélion Paints a Picture”: “clear, monumental, rounded forms and quiet metallic tones, which give an impression of tranquility and unclamorous strength.” 10

Above the piano is the print by R. B. Kitaj, an Ohio-born painter living in England, whom Ashbery has praised for his “literary qualities.”11 Entitled “French Subjects,” this collagelike work contains three line-drawn portrait heads, one labeled “A. Legros,” the others unnamed. The name “Gerard Phillipe” banners across one section of the piece; ten stylized soup bowls in two rows stand upside-down at top left; and at lower right, we are given a mysterious photograph-derived image of two people in coats, walking toward a building with an inverted horseshoe and the word “cottage” on its side. The work is inscribed by hand: “Kitaj (proof) For John Ashbery, love.”

Finally, with the bibelots and curios on the piano—some art pottery, some music books, a marble sculpture of something between a chess bishop and a lighthouse—is a stand supporting a canvas painted by the British artist and poet Trevor Winkfield. The small, strange, jewel-like images, in flat, bright colors, include a pair of dice, a fly, two jingle bells, and the lower halves of a few flowerpots. A gift from the young artist during Ashbery’s long hospitalization in the 1980s, its back is inscribed: “Fragment,” “this, my first canvas in seventeen years, for John Ashbery abed, May 1982.” Needless to say, Winkfield is another exceptionally literary painter, in fact a Roussellian, and a dear friend of Ashbery’s.

The library at the left of the hall seems to be the forest counterpart of the lakelike music room. Where the music room is decidedly French, both antique and modern, the library is peculiarly Germanic, in a Black Forest fairytale way, Victorian and gnomic, not to say gnomelike. This impression is chiefly conveyed by the oak paneling and the large pieces of furniture: there are no fewer than five big upholstered armchairs arranged in a circle here, with carved arms and legs, leafy fabrics or figurative needlework, antimacassars and pillows. Small coffee tables between them support Tiffany lamps. The three floor lamps are carved of large wooden posts, adding to the woodland feeling, further heightened by a leafy potted palm. This room’s paneled ceiling and high wainscoting can be seen in the book American Victorian.12 The books that give the room its name—specially bound books and journals, including an entire set of Art News—are in the background, behind built-in glass-doored shelves.

This room, too, has a special place for the American: on the mantle, Ashbery displays a select collection of American art pottery, which completes the Midsummer’s Night’s Dream spirit of the atmosphere. Small pots and dishes, mugs and vases, jars and candlesticks, in green and brown earthtones, glowing blues and turquoise, iron pinks and ochres, are reflected in the mantelpiece mirror. An old crackle-glazed blue-on-white Dedham rabbit plate rests in a stand as a centerpiece within a square niche above the dark tile of the fireplace, below the mantle. One shelf holds a Roycroft metalwork vase. These pieces are from the studios of small artisans or industries from all over the country, both older and newer kilns—Weller, Van Briggle, George Ohr, Marblehead, Gruby, Hampshire, Jugtown, Cowan, Frankoma, Fuller, Roseville, and Prang. While many can be identified by the potters’ marks, Ashbery has collected not only the pottery but also books about it for many years, and he is able to recognize the origins and value of little dishes and trays that most people would overlook in a dark thrift shop. Like Puck and his band in an Arthur Rackham illustration, the grotesque and graceful forms of the earthenware gathered on the mantle seem to dance in trees above the heads of the poet’s afternoon guests.

Another whimsical Victorian is represented here: above the high oak panel hangs a colored print by Edward Lear, one of his sketchbook Italian scenes, labeled Ponta Pingiana. There are, in addition, three Piranesi prints: the Veduta di Franco del Campidoglio, Rome, in black and white; a 1777 scene of the Porto Orientale, showing the harbor surrounded by ornate statuary; and a vista down a curving street, the Veduta della Gran Curia Innocenziana, filled with three-story urban façades. Finally, there is another Englishman’s view of Italy, a large colored print of Venice by J. Alphege Brewer. The combined effect of the prints is light, airy, and at the same time rather literary, appropriately. Are they far-off scenes glimpsed through the forest trees, or endpoints of maps of where we might be off to next? So detailed but so unobtrusive, they invite and avoid deeper study.

Photo by Ahndraya Parlato

The dining room is papered with real Lincrusta Walton, the wallpaper immortalized by Oscar Wilde as the one thing he most missed while in Reading Gaol. The room represents the sumptuous Victorian style, with built-in curved-glass cupboards and a stained-glass window. The table and chairs, as described in American Victorian, were “built especially for the room, with an edge molding of the same egg-and-dart design as the handsomely paneled woodwork and cabinets,” and other “high-style Colonial Revival flourishes.”13 The poet searched long to match a missing shade for the chandelier, which now has all four golden Steuben Aurene glass shades, like the one in the music room. The warm golden light is deepened by the oak woodwork and burnished by the stained glass above the mirror at the back of the room, with its harvest grapevine motif. In one corner, a large embossed brass plate with a tavern scene gilds the lily. This item came from a Rochester, New York, antique store at the top of the block where Ashbery lived as a child with his grandparents during the school year.

The ceramics on the shelves and enclosed in the cabinets of the dining room include Czech pottery, blue willow, a large collection of French matchholders that the poet gathered during his years in Paris, plates with scenes from Roman history and captions in French, and a Little Orphan Annie mug with the balloon, “Didja ever taste anything so good as Ovaltine? And it’s Good for yuh, too—.” There is a blue-transfer plate featuring American poets: Bryant, Holmes, Lowell, Whittier, Poe, and Emerson, with Longfellow in the center. On the back stands a pair of pouter pigeons by Goldschneider; on a side table are pieces of glassware: a Dorflinger spiral-stem candy dish, a Daum potpourri bowl, and a mottled yellow Loetz dish.

Over the mantle, which is full of Teplitz amphorae and German art glass vases, a portrait shows a rather beefy sea captain, no relation to the poet, painted perhaps by Samuel F. B. Morse. He’s there because he’s supposed to be there, one of the elements in Ashbery’s exquisite Victorian parody, if it is a parody. There is also the requisite still life of sliced fruits and open pomegranates, with an indecipherable signature. A print of Guido Reni’s Aurora hangs above the left cabinet, and there is a convex mirror at head-height as you turn left into the butler’s pantry. That mirror, of course, is tantamount to Ashbery’s signature on the room, which is one of his favorites in the house.

A doorway at the back of the left wall leads to the butler’s pantry, a narrow room or a very wide hall between the dining room and kitchen. There are counters on either side of the passage, a window onto the backyard at the right, and cupboards at the left that reach straight up to the high ceiling. On these shelves are more ceramics and glassware; on the walls, a wonderful William Morris print paper in brown and rust tones, his “Tobacco Leaf” design. The Fiestaware is stored here, as well as a number of Czech ceramics and a collection of fake food: clay vegetables and breads; wooden, wax, and plastic fruit. There is an old black plastic handset telephone—with a real dial—on a phone shelf just before the kitchen door.

Under the window, a marble counter with a copper sink is covered with bottles: this side is the bar. And there are appropriate paintings: a still life of Bombay gin bottles by Archie Rand, and a small piece by J. Shannon, a 1979 portrait of Walter Hopps (1932–2005; a curator of twentieth-century art at the Menil Collection museum). Hopps wears rolled-up shirtsleeves and a bright tie, and stands with a drink in one hand, the other hand in his pants pocket. A cartoon from 1924 is also framed, showing two cute urchins and a pup with a bow, entitled “L’heure du cocktail.” A tin advertising sign reads “Drink sunspot / bottled sunshine.” And there is a coaster from Harry’s New York Bar, Munich: two dancing grasshoppers in top hats.

Photo by Ahndraya Parlato

In the kitchen, the warm light from side and back windows and the back porch door is complemented by the yellow and white paint of walls and ceiling. The room is full of useful things and of less useful but more interesting collections, including at least nine tin fish molds on the walls and several yellowware bowls of all sizes on a stand. There are two walk-in pantries, a smaller one with china dishes and glassware, and a huge one for cookware with an entire wall of shelves full of cookbooks. The house’s original woodstove stands at the left side of the kitchen table; painted a shiny black, it now supports the microwave, and its belly is full of boxes of tea as well as a blue glass jar holding peppermint grown and dried by the poet himself. On the refrigerator, a magnet shaped like a pack of Dentyne chewing gum holds up a coloring-book picture of Jim Henson’s Muppet Miss Piggy, reading a book to her dolly; it has been colored by Sarah Megan Williams, a six-year-old friend. Old advertising art dominates the walls: a poster for “Genuine Butter-Nut Bread” features white slices floating in an arc through the air down to a silver platter. And a placard for “Uncle Wabash Cupcakes” may be a subliminal early booster for integration: two white-frosted, five chocolate-iced cupcakes together on a plate, with old Uncle Wabash, a grizzled African-American, playing banjo in the lower left corner. Over the sink, a large metal sign, unframed, in yellow, red, and black, reads “Clabber Girl, the double-acting baking powder.”

There is a back staircase from the kitchen to the second floor, but for the proper way to go upstairs, we retrace our steps through the dining room so as to proceed up the formal front stairs to the upstairs hall. This staircase is stunning, not only for its showcase stained-glass window, but also because of the twenty Japanese prints purchased by Ashbery in the fifties in Paris. Their style is mostly after Hiroshige, and they depict bridges in rain, seashore, snow on sea and hills, street scenes, green mountain paths, a house on a sea cliff; there are two of Europeans, and there are “Yokohama prints” with geisha, as well as a view of Mount Fuji. There is also a typical ukiyo-e triptych of four figures. Glimmering lushly from the shadows at either side of the window, on two small built-in corner shelves, are two vases of what is known as Goofus glass: these shimmery painted objects, the poet says, are “really basically junk, although now of course there are books on them.” The window, which dominates and illuminates both downstairs and upstairs halls, has a landscape motif, with a design of mallows in the foreground and the purple Catskills in the background, all encircled by blue ribbons and wreaths.

The upstairs hall has a large travel poster of the town of Carpentras, a detail from a nineteenth-century painting of this walled city of North Provence in the south of France, a Jewish center in the Middle Ages. Ashbery visited there long ago, and again with Francis Wishart, son of the painter Anne Dunn; they saw the old synagogue and subterranean mikvah baths. Views of two German towns, Andernach and Neuwied, by the painter Schutz, hang here as well. A very small landscape view of Chillon, with a butterfly ship below the citadel, came from Ashbery’s grandparents’ home. Of its provenance, he says only, “I don’t know who did it or where it came from.” There is an old mirror topped with yet another reproduction of Reni’s Aurora, hanging above the round table with the phone—again, a nice heavy old-fashioned black 1950s dialer. On the table is also a dome-shaded Tiffany lamp, featuring a geometric pattern of circles and lines in monochromatic tones of pale gold.

This is not to say that the back stairs have been neglected: on the contrary, there’s not an inch of wasted space here. An amazingly eclectic gathering of prints and images carpet the cottage-style green-flowered wallpaper. At the foot of the stairs is a large frame holding the separate sheets of a “Tom Thumb’s Alphabet” by Edward Dalziel, from an 1867 publication entitled The Child’s Coloured Gift Book (the entire book can be viewed online here). Each letter has a figure or two in caricature, and a rhyme, as below:

A was an archer,

who shot at a frog.

B was a Butcher,

who had a great dog.

C was a captain,

all covered with lace.

D was a drummer,

who played with a grace.

E was an Esquire,

with pride on his brow.

F was a Farmer,

who followed the plow.G was a Gamester,

who had but ill-luck.

H was a Hunter,

who hunted a buck.

I was an Italian,

who had a white mouse,

whom John the footman

drove from the house.

K was a King,

so mighty and grand.

L was a Lady,

who had a white hand.

M was a miser,

who hoarded up gold.N was a Nobleman,

gallant and bold.

O was an Organ-boy,

who played for his bread.

P a Policeman,

of bad boys the dread.

Q was a Quaker,

who would not bow down.

R was a Robber,

who prowled about town.

S was a sailor,

who spent all he got.T was a Tinker,

who mended a pot.

V was a Veteran,

who never knew fear.

[U is missing forever from here.]

W was a waiter,

with dinners in store.

X was expensive,

and so became poor.

Y was a Youth,

who did not like school.

Z was a Zany,

who looked a great fool.

As we climb the stairs, when we can finally tear away from that extravagant and scary children’s alphabet, we find a print of Edward Burne-Jones’s Galahad and his steed; a lonesome pine on a trail in a 1920s colored photo of Yosemite; a photo of Nita Naldi wearing pearls and a high, pointed headdress, not the Theda Bara clone she appears to be but, says Ashbery, “someone in her own right”; a print of Hans Holbein’s Erasmus; several etchings, including two landscapes, one of a cloister with oxen on the road, signed by H. Toussaint; a geyser from Watkins Glen, which Ashbery calls a “childhood haunt”; a color poster of Diaghilev’s Ballet Russe Puss in Boots; and as a grande finale over the stairs, a large color movie poster of Rin-Tin-Tin, Jr., a German shepherd posing vigilantly on a mountain ledge at sunset.

There are also a couple of pieces by Maxfield Parrish, “Interlude” and “Daybreak,” both from 1922; this Parrish collection continues in the bathroom, where three more enhance the paneling: “Circe,” 1907; “The Rubaiyat,” 1916 (originally art for a Crane’s Chocolates box); and a Collier magazine cover of 1908, a landscape with a figure, a gift to Ashbery from the poet Bill Berkson.

And there’s more on the stairs: “Liszt’s Matinee,” which Ashbery says is the famous print of Liszt and his circle by Joseph Kriehuber; “The Very Last Polka” by Francois Bernard, an 1800s sheet-music cover with a city evening scene and horse-drawn carriage; two tinted photos, “The Garden Gate” and “The Swimming Pool,” maybe by Wallace Nutting, a northeastern photographer popular for garden scenes and ladies in nineteenth-century dresses. There are ruins of the Roman Forum; Zurich’s bridges; the Via Dolorosa, Jerusalem, again from his grandparents’ home; a “Boy in Orchard,” which seems to be a three-dimensional embossed print of a child in a hat; one of those comic prints with the legend “Ne buvez jamais d’eau”; a Raphael Madonna and Babe; and the Uneeda Biscuit boy in his yellow slicker, carrying a box with the Nabisco logo beneath his arm.

We are rewarded at the top of either staircase by an invitation to the upstairs sitting room, actually the very important location of the television, VCR, coffee table, and six-o’clock news. Today there is an electronic remote-control whoopee cushion on the round Formica-topped table in front of the main Potato Couch, as well as a wind-up metal duck on a motorcycle with a whirligig on its head, a gift from the poet Ed Barrett (this same duck can be seen in a mail-order catalogue called Russian Dressing); a porcelain gnome with a pipe, inscribed “Dingle”; and a plastic windup walking Christmas tree about two inches high. The table also holds the usual collection of magazines (Gourmet, Old-House Journal), Michelin guides, the latest Book Barn finds, poetry journals, biographies of musicians, and movie guides, especially The Psychotronic Encyclopedia of Film by Michael Weldon.

On the mantle opposite the couch are more serious, or at least older, porcelains: Staffordshire figurines of dogs and lovers, a miniature bust of Byron. The William Morris wallpaper here is again “Tobacco Leaf,” in a bittersweet color. A bibelot shelf in the corner holds a good-sized collection of miniature shoes, fashioned in glass, porcelain, metal, and other media. There is a Nordic Track indoor ski machine. There is a miniature table that seems to be made of buttons. The bookcase is full of cassettes of cartoons, old B films, lots of “Mad Movies” from San Francisco, and old SCTV reruns, as well as books about Hollywood, music, and cinema.

Despite the wealth of pop culture here, the nine paintings in the room elevate the atmosphere even with the television on. Many are pieces to which Ashbery is particularly attached: a Jane Freilicher still life with a copy of ARTNews; Anne Dunn’s “Orchard” of 1989; an Elaine de Kooning garden, Casale Sonnino, watercolor on paper, inscribed “Happy birthday 9/20/81”; and a Rodrigo Moynihan painting of light bulbs. Over the mantlepiece is a large print, captioned “Grand Theatre Chalet.–Fond.” It shows a mountain house with a brook on the right: Ashbery identifies it as an image d’Epinale, the town in eastern France famed for its colored chromo illustration industry. There are three Hélions: a sketchbook leaf showing a Paris street scene of people walking between parked cars; a watercolor study for a large oil painting of three figures, 1937; and one piece inscribed to Ashbery, showing the studio where the painter’s wife lived, the flat space of the roof, chimneys in the background, a bridge leading over to his studio. Above the couch is one of Jim Bishop’s huge colorfield paintings, whitish blue, blue, red, and green.

In the upstairs library across the large central hall, white bookshelves rise from floor to ceiling along three of the walls, interrupted only by windows and a fireplace. Once a bedroom, this study is now the main repository of reading material in the house, and the working office for Ashbery, holding both the computer and the stereo equipment. The titles on the shelves are mostly fiction, philosophy, mysticism, and biographies, as well as records, tapes, compact discs, and books about music.

The Morris wallpaper here is the Iris pattern, a deep turquoise floral, not much of which is visible behind the bookshelves. It harmonizes with the faux-malachite marbleized fireplace and with the Larry Rivers double portrait of Ashbery and Kermani, “David and John,” 1977. The painting incorporates as background several lines from the poem “No Way of Knowing” from Self-Portrait in a Convex Mirror, beginning with “And then? Colors and names of colors.” There are old family photos here—actual family this time—on the mantle and above the computer desk: one shows Grandfather Ashbery and the soccer team he coached at a Pennsylvania school where he taught in the 1880s. The closet of this room holds Jane Freilicher’s unfinished portrait of Ashbery, painted about 1965, and another piece of French antique ephemera, the backdrop for a puppet theater, a set of scenes including railroad, towns, and a cityscape. On the walls hang Anne Dunn’s red flower/phallus image, 1962; a poster of Gentileschi’s “A Sibyl,” circa 1620, from the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston; a small canvas by Hélion of Belle Isle en Mer, showing a port scene at Amici, with two white brushstrokes like a heart or dove in the sky, tethered boats, and boxy houses; and a modern New York cityscape by Darragh Park, entitled “Freeze,” set near the poet’s apartment on 22nd Street in Chelsea.

There is another small office upstairs, in a bright windowed alcove between the sitting room and the guest bedroom. The desk in this office faces three small stained-glass panels set into a large bay full of potted plants. Another small bookshelf holds odds and ends, children’s books, gardening titles. There are four more pieces here by Winkfield: one mysterious puzzle featuring a 1920s-garbed lady, a gagged but pointing boy, and a leopard in a cage; two from his series “Marine Architecture”; and one mandala design of a bearded face, hardware nuts, and mirror, multiplied on a quadrant. On the right wall are three small nineteenth-century landscape drawings by minor artists, pale sketches: an Adolphe Appian of a fisherman in a mountain stream; an Antoine Chintreuil shoreline; and a seascape by Antoine Vollon. In contrast is the abstract piece by the Texas-based painter Robin Utterbach, behind the desk.

The master bedroom is a deep lagoon, a place for a lorelei or a kraken to dream. As Descartes and Proust did in their rooms, Ashbery spends a good deal of time in his large brass bed here, especially weekend mornings, with the classical radio station out of Albany and the New York Times. “White Pimpernel” Morris wallpaper dominates the walls with cool greens and creamy white flower petals in Celtic swirls. There is a flowered chaise longue and wall of books, mostly art history and art catalogues, collections of classic comics, travel, antique magazines, and the histories of various cities and locales, especially New York, Paris, and the Hudson Valley. A white door leads outside to a screened sleeping porch, furnished with white-painted wicker chairs and old rockers, hung with baskets of ivy, spider plants, and bleeding-heart or fuchsias. The porch looks west: the poet sits out there during summers and watches his garden, the sunsets, and in particular one huge old arabesquing elm tree way down the block. There are three large Victorian houses along the street and alley, rising over a new glass solarium built in the appropriate Gothic style.

The paintings in this room again include Hélion, a small sketch made for Ashbery in 1962 of a garden with a wheelbarrow; and Freilicher, a painting of a basket of Queen Anne (oxheart) cherries, inscribed “Happy Birthday John, July 1977”; another Freilicher, “Sunset,” shows her penthouse view, painted some time between 1969 and 1988. There is also a funny Red Grooms, titled “Summer Still Life,” featuring a can of Barbasol, razor, screen with seven hooks, a sailboat, and a fly, dated 1978; a very small piece by Danny Moynihan of two white stones; the Alex Katz portrait of Pierre Martory with a pipe, from about 1969, made from a metal cutout print, of which this image is a silkscreen detail. James Schuyler refers to this piece in his poem “Letter to a Friend: Who is Nancy Daum?” from The Crystal Lithium.14 There is also a sketch of Ashbery’s grandparents’ summer home in Pultneyville, New York, given to him in 1985 by Philip Bornarth, a painter who taught at Rochester Institute of Technology (he retired in 1999), and his wife Sylvia. “This was a summer cottage, remodeled for winter after his retirement,” says Ashbery.

There are two paintings by Neil Welliver: both Maine landscapes, one entitled “Drowned Cedar,” with a dead bough in the water; the other a view from his home. The latter is a small version of a larger painting that Ashbery once arranged to appear on the cover of ARTNews, when the original cover fell through and left editor Thomas Hess strapped, thereby jumpstarting Welliver’s career. Welliver painted this small version and gave it to Ashbery to thank him.

A Color Chart over the radio by the bed features several natural and manmade objects to illustrate the colors of the spectrum; it was acquired from the same Paris shop as the puppet-theater backdrops: “a shop full of wonderful old toys,” says Ashbery. The Joseph Cornell poster for a 1977 show features the print that appears on the cover of Ashbery’s collection Hotel Lautréamont. On the dresser, with a photo of his mother, is another of Ashbery in suit and tie from 1956 at an aunt and uncle’s; and what he calls a “daub” inscribed “Happy birthday,” by Mary Abbot, a friend of the poet Barbara Guest.

Adjoining the master bedroom—connected, in fact, by a walk-through closet—is the guest bedroom, papered with a truly eye-teasing Morris floral of white, yellow, green, blue, pink, gray, and other fresh, clear hues just a bit away from bright, with a pattern just short of busy. If the other bedroom was a lagoon, this one is a summer meadow. White-painted bookcases, woodwork details, and the yellow tile fireplace harmonize with and calm the excitement, which is, however, revived in miniature with a collection of “end-of-day” glass on the mantle, primarily vases with swirling color-dot patterns in every shape and size. Ashbery is justifiably proud of this room’s faux-bamboo bedroom set of birds-eye maple; he has seen the same in a museum. A little ceramic lady with a fan kicks up her leg on a swinging hinge on the dresser top. The bookcase holds a collection of poetry: whether the poet stores these titles here because he likes the thought of these books in this particular room, or because he doesn’t want all those other voices right next to his own bed, I am not sure.

Given the energy of the backdrop, the walls here have been hung with an appropriately quieter collection of smaller images: a Currier and Ives print of Saratoga Lake; an atypical Freilicher, from her short-lived abstract period, captioned “Near the Sea”; a black and white Corot print, “Une matinee,” of dancing nymphs and sirens; a 1979 painting by Susan Shatter, “Scarlet Sunset,” showing a view of Lake Wesserunsett, Maine; another print, the “Horse Fair” of Rosa Bonheur; a drawing in pen and ink over pencil of loopy calligraphic figures, made by Raymond Mason, an English artist living in Paris and inscribed “1984, for JA”; another Bishop, this one a dark abstract gouache, 1960; by Nell Blaine, a 1953 ink sketch of a forest pond; by Joe Brainard, a wonderful flowery collage and watercolor entitled “Garden IV,” of about 1969; a framed oval print of a young girl after Jean-Baptiste Greuze—called “The Broken Pitcher,” it is a late eighteenth-century French allegory of lost virginity. “He did a lot of these!” remarks Ashbery. With the kicking lady on the dresser is a Hélion sketch of three musicians from 1968, when, caught up in the student movement, the artist made many such street scenes.

The guest bedroom is the last of the main rooms on the second floor; the bathroom is the only one I have not described, although, with its Rookwood tiles, cast-plaster ceiling moldings, and eight-foot tub supported by plump little caryatids, it certainly holds its own with the other rooms. It is, obviously, a most magnificent antique bathroom, one of the delights of which includes a bottle of Acacia Violet cologne given to the poet by Schuyler.

There is one last place to view: a doorway between the entrances of the two bedrooms leads up another flight of stairs. The attic staircase, unpapered, offers an illusion: its old painted plaster seems to be hung with one solitary frame about two feet square. But when we approach it, we discover that, no, it is not a frame, not a picture within a frame, but an air vent, nicely made and finished as if it were a glassless window. I am fond of this error, which I always make: expecting to see a work in a frame, I find only space through which I can look down and see the images hanging in the hall of the back staircase. I find it surprising, funny, mysterious, serendipitous, and literally absolutely clear: like so much of Ashbery’s poetry.

A little guest bedroom, once a maid’s room or nursery, opens at the top of these stairs. Two old twin beds have handwoven navy and white wool-and-cotton coverlets, one of which was woven by an Ashbery ancestor and dated 18-something. Here, on another wall of bookshelves, are the poet’s collection of French titles and the entire Anchor Bible. There is a large Hélion poster from 1980, published by the Galerie Karl Flinker, of a nude woman, with a baguette on a tableclothed table. Between the two beds hangs a large, handsome Kovac Star Map, a dark blue rectangle with white circles sprinkled with stars, and in a small frame on the right side of the room is the cover of Childlife Magazine from Christmas 1937.

1Contemporanea (January 1990), pp. 52-57. With photographs by Ken Schles.

2New York (May 20, 1991), pp. 46-52.

3Sienese Shredder (2008), pp. 20–23.

4“Slaves of Fashion,” The Night Sky: Writings on the Poetics of Experience (New York: Viking, 2005), p. 180.

5“Outside the Shady Octopus Saloon,” New York Review of Books XLI.10 (May 23, 1993), pp. 32-33.

6Complete Works, trans. Wallace Fowlie (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1970), p. 193.

7“And Ut Pictura Poesis Is Her Name,” Selected Poems (New York: Penguin, 1986), p. 235.

8“Guest Speaker: John Ashbery, The Poet’s Hudson River Restoration,” Architectural Digest (June 1994), pp. 36–44.

9Reported Sightings: Art Chronicles 1957–1987 (New York: Knopf, 1989), pp. 181-187.

10Reported Sightings, p. 59.

11Reported Sightings, p. 300.

12Lawrence Grow and Dina von Zweck, American Victorian: A Style and Source Book (New York: Harper and Row, 1984).

13American Victorian, p. 129.

14Selected Poems (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2007), pp. 85-90.