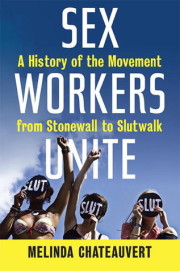

A History of the Movement from Stonewall to Slutwalk

A History of the Movement from Stonewall to Slutwalk

Melinda Chateauvert

Beacon Press ($26.95)

by Kelsey Irving Beson

Although Sex Workers Unite’s language is dispassionate and academic, the story that it tells can be heartbreaking. It is well known that sex workers are the frequent targets of violent individuals; far less notorious is the fact that they also suffer at the hands of lawmakers and police, who can be as hateful as vindictive johns, but are doubly dangerous because they are in a position of systemic power. The scope of this brutality would be difficult to explain with mere statistics, but Melinda Chateauvert gives it a human face when she relates individual stories. For example, in 1989 District of Columbia police spontaneously rounded up about twenty-five street-based sex workers and forced them to march to Virginia. A Virginia congressman’s response was to decry the action as part of a legacy of DC sending its “sewer sludge, garbage, and convicted felons” outstate. Chateauvert effectively exposes this combination of systematic bigotry and personal brutality that enables people such as Gary Ridgway, a Seattle man that murdered at least forty-eight women. When he was finally brought to justice, he stated that “I picked prostitutes because I thought I could kill as many of them as I wanted without getting caught.”

In spite of these emotional stories, the tone of Sex Workers Unite is not overwrought or maudlin. The reader never gets the impression of being invited to pity the book’s subjects. Chateauvert is also realistic about the everyday tedium of sex work, which entails quotidian drudgery remarkably similar to that of more conventional service industry jobs. Alienation is a frequent complaint, as are physical problems associated with repetitious motion (one study of professional strippers, for example, cited high heels as a more pressing health hazard than STDs). This clear-eyed analysis is refreshing compared to the common hipster narrative of sex work as an empowering, sexy performance rather than a job done by ordinary people. The author’s focus on the work rather than the sex aspect also enables her to build a connection with the overarching fight for unionization and labor rights, especially in the wake of NAFTA. The struggle for humane working conditions and a living wage in the face of greedy bosses and indifferent authorities can and should be included in the larger narrative of U. S. worker’s rights.

The book also connects sex work activism with many other midcentury countercultural movements and concepts. These include the shift toward increased sexual honesty and freedom, the debate over privacy and civil liberties, and AIDS activism. Chateauvert pays close attention to the concept of intersectionality, and race and gender normativity (or lack thereof) figure heavily into her analysis. Big personalities abound, with sex work activists such as Margo St. James and Flo Kennedy instigating riotous (but relevant) pranks such as “awarding” a giant keyhole to nosy San Francisco police or judging an Anita Bryant drag contest. The focus on grassroots activism really emphasizes that sex workers are free agents that can improve things for themselves.

The author’s thesis that her subjects are capable individuals, not a crowd of victims, is well-supported, and it works best when she justifies it with specific events and quotations. Unfortunately, the book is liberally peppered with snarky asides about pretty much everyone that isn’t a sex worker. Combined with a rhetorical strategy that often consists of describing (purportedly) opposing groups and their endless clashes with each other, this makes parts of the book seem unnecessarily combative and almost whiny. For example, when discussing AIDS activism during the 1980s, the author decries the marginalization of sex workers by “gay male” movement leaders. When these men (none of whom, apparently, were or cared about sex workers), finally extended a hand of welcome, sadly, it did little good:

The result [of inclusion] often looks more like a poor woman’s fixed-up ranch facing foreclosure than the professionally rehabbed and decorated city brownstone of a married professional gay couple.

This reference to the stereotype of the wealthy, materialistic gay urbanite feels especially pernicious when one considers that this refers to a time before any kind of legal recognition of gay couples actually existed. The emphasis on antagonistic differences is so ubiquitous that it ventures into the absurd—breast cancer and AIDS framed as competing diseases whose activists have no appreciable overlap, for example.

The bulk of the author’s ire is overwhelmingly directed toward feminists of all stripes; including radical, liberal, separatist, and mainstream; even modern-day sex-positive allies can’t get a break. It is here that the binary framework is most obvious, and possibly least appropriate. Admittedly, the 1970s and 1980s were an era of rampant and vicious infighting among feminists, and by no means should this be whitewashed or sanitized. However, “sex worker” and “feminist” (even radical feminist) were not discrete categories—some of the most vocal leaders in the movement to abolish sex-for-pay (seen by some feminists as an intrinsic part of patriarchy) had been sex workers themselves. This fact is glossed over in favor of literally designating sex workers as “bad girls” and everyone else as “good girls,” terms that make numerous appearances throughout the book (lesbian separatists especially might have been surprised at the “good girl” designation). The recriminations against feminists (which frequently lack citations or attributions to actual people) include everything from vague implications of joylessness to the very serious allegation of “successfully suppress[ing] safer-sex literature,” essentially accusing feminists of endangering people’s lives. Indeed, there are parts of the book that make it seem as if other women were the authors of societal misogyny, instead of fellow casualties.

Sex workers are a largely subaltern group, and hopefully this useful book is a catalyst for the beginning of a scholarly, serious documentation of their history and activism. Chateauvert’s effort is well-executed, her quest laudable, and her passion palpable; these qualities save Sex Workers Unite from drowning in its own vitriol—but only just.