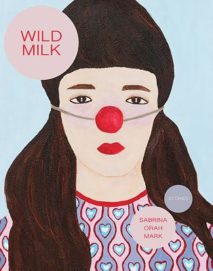

Sabrina Orah Mark

Sabrina Orah Mark

Dorothy, a publishing project ($16)

by Rachel Hill

It is difficult to know how to define what scuttles, mutters, and lactates across the pages of poet Sabrina Orah Mark’s newest collection Wild Milk. Are these bewildering fables? Mumbling poems? Truncated shorts? Whatever they are, one thing is clear: They are excellent.

Surreal and experimental, it is no surprise that Wild Milk is released by Dorothy, a publishing project, a small press established by Danielle Dutton specializing in literary fiction by women. Among Dorothy’s other titles is The Collected Stories (2017) of surrealist artist Leonora Carrington, a writer of bizarre fairy-horrors which has clearly influenced Mark’s work.

The collection’s title story, “Wild Milk,” handily encompasses many of the book’s consistent themes of motherhood, anxiety, and the limits of language, as expressed through a glitchy dialogue and veers into the unexpected. The protagonist, a nameless mother, leaves her child in the daycare of Miss Birdy. Later, discussions about this child’s behaviour quickly devolve into musings on ephemerality: “‘It was a sound that sounded like a sound,’ says Miss Birdy. ‘Like a sound a sound would make.’” Mark’s chanting words use absurd tautologies to breed half-glimpsed new meaning and musicality, imbuing the concept of sound with an almost creaturely agency.

“Tweet” also mobilizes repetition and the absurd, to illustrate how perception is put through the daily meat-mincer of social media. In a frenzy, we are told, “The towel is tagged. We take turns touching the tag. God, it is lovely. It is a lovely, lovely tag. That we should all one day be tagged by a tag as lovely as this tag.” With the relentlessness of an out-of-control conga line, “Tweet” excellently captures a culture of constant distraction, where the glitter of temporary stimulation runs concurrently with the news cycle’s breakneck speed. Rather than mothers, here we are all rendered children, breathing only through the oxygen of attention. To extract oneself from this digital twittering milieu is to become exposed, left leaderless and asking, “Who will keep us warm? How am I supposed to know where to go?”

Lack of substantial leadership is elegantly addressed in the post-apocalyptic “For the Safety of Our Country.” It begins with a list: “Today is a new batch. The Presidents come from all over. Perishable Presidents in thinning sweaters. Presidents bent like moons.” So the Presidents arrive at the White House, disembarking from a school bus like a band of unruly children. Set against a background of environmental collapse, where “it might have rained had rain not ended,” the world the Presidents should save and protect instead becomes a source of extreme discombobulation for them. With its sense of metaphysical grief and inured disappointment, this story demonstrates how necessary Samuel Beckett and the theatre of the absurd are for Mark’s work.

On the whole, these stories have the saturnine gorgeousness of a lepidopterist’s collection—each story a different breed, each sentence a different wing-facet, each word another enticement. Mark’s work crystallizes how the absurd is not only a reasonable response to our untenable now, but displays how the silliest-seeming of responses can harbor the most succinct of critiques. Alongside its lavish sparseness and knife-fight speed, these stories are also surprisingly funny. We may have heard of writing as protest, but here is writing as riot.