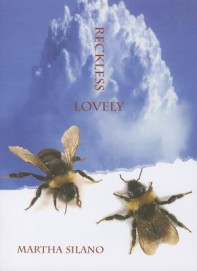

Martha Silano

Martha Silano

Saturnalia Books ($15)

by Janet McCann

Martha Silano’s fourth collection Reckless Lovely is a rapid trip that seems to start in the middle of a breath. Its first poem plunges right into the middle of the Big Bang, which is presented as the product of a mad chef:

begins with a dash of giant impact, a sprinkling

of moonlets, pinch of heavy bombardment.Sift in crusty iron sulfide, fricasseed stromatolites,

one level teaspoon cyanobacteria. Slowly dribbleammonia, methane, hydrogen; drop a dollop

of ocean.

So the Big Bang is a recipe, and creation is represented as cuisine—who is this chef, though? The speaker, the goddess? This explosion introduces us to a markedly female world characterized by a fast-moving stream of images and ideas, giving an impression of uncontrollable life burgeoning. There is a great deal of science in the poems, but redefined in women’s terms, often having to do with cooking and birth imagery. And the poems never slow down, not even by the last line of the book; they yank the reader along in their tide. No chance to ponder an image or metaphor—you are already in the next one.

With their high energy and their tendency to pile up ideas, concepts, and details, these are not easy poems—ciliegene, stromatolites, Siphusactum gregarium, collembolan, Megatherium, placoderm, and bits of Italian appear in the first three pages of poetry. Yet the poems are not unclear. The sense of the proliferation of things sweeps knowns and unknowns into the same current. The music of the language helps provide unity within poems, and often signals the epiphany or the emotional high point, as it does in “Constellation”:

What’s the weight

of Cygnus? How long‘til my castles topple, sing

a crash of high-stakes half-notes? O hydra, O heron, O howling

hound not howling—the whole dang lotof tinsel and ills, lilt of every living cell.

The alliteration, assonance, and other echoings add up to an intense climax that seems to be both celebration and mourning. The poems crackle with humor, too—the same style of piling up images produces a smile, if not downright laughter, in “Mystery of the Bra,” which begins with a brassiere incident and then jumps into bra history:

Bra not showing its face, bra with a history like that 600-year-old

breast bag stuffed between floorboards in an Austrian castle,raggedy sack of linen and lace that had lifted white-sand mountains,

milk chocolate double scoops. With sexy boost this land-lesslandmass, this dollop-y desert dessert unloosed, shouting

she should never have got with that guy—never that bush,those boys, that sequined sapphire dress, never this plunge-maker

plunging from a cherry red Camaro, bereft of what lifted its lace.

Toward the end of this collection, the poems seem to suggest a quirky, exploratory metaphysics; if there is a God around it is a process God or even a God process. Silano often writes about religious subjects—her titles include “Saint Catherine of Siena,” “God in Utah,” and “What Falls from Trucks, from the Lips of Saviors.” Of course, writing about religious topics is not religious writing, and some of these poems are clearly satirical, but they also question, evaluate, and approach the spiritual. Perhaps the clearest of these is “Saint Catherine of Siena,” which explores the strange and drastic contradictions of Catherine’s life:

Short and frail. Sweet curmudgeon. Hairshirt clad. Bed of thorns.

When forced to eat, stuck a goose feather down her throat

till she puked. Willingly kept down only her daily communion wafer,though for her friends she whomped up loaves of focaccia, contucci,

panforte, prayed for miraculous multiplicities—truffled funghi

pork loin alla romana. Made an empty barrel gush Chianti, but her drinkof choice? Pus from the putrefactions, sores

The poem gives a rapid-fire investigation of what Christianity offers and what gets in the way of accepting it, and then turns to a speaker’s childhood friend who apparently is trying to convert her, pointing out

the irrelevance of my pantyhose-with-a-run attempts at reasoning

out God—suggests Pascal’s Gambit. But I’m already betting, I tell my friend,though I’m not, keep dissing Him, about which dissing He shared with his

mystical, monastic wife: this is that sin which is never forgiven, now or ever. Infinite mercy

with a louse-sized caveat: surrender to be victorious; reject sin, befriendthe trespasser, be in the world but not of it, endless paradoxical paradise

The interest in spiritual experience threads through the last poems in the collection, though the speaker seems to find true transcendence in nature, particularly nature revealed through science. Yet the uncoverings always seem to point to deeper mystery, as if under all the surfaces lurks the mystery of life itself. “Ode to Mystery” concludes:

Mystery of nematodes bravely clinging as they take

their snaky ride not unlike a tunneled, caustic waterslide—

circular, orificial. Who really deserves the shiny trophy:we, who launch our dinghies into the roaring unknown,

or the barnacles hunkering down for their twice-dailydrought? Language is spiffy, but lo the hocus-pocus

of pheromones, crickets and cockroaches emittinglickable seductions. That anything lives at all, that fog

rolls in and out, that milk spurts from the teat, that laughtererupts when the child reads buc-a-BAC, buc-a-BAC,

and the boy in the story tucks his chicken into bed.

Proliferation and story weld together in this celebration of becoming. Silano’s work has already won many prizes and awards, and Reckless Lovely will be certain to win her more acclaim.