Stacy Hardy

Stacy Hardy

Pocko Editions ($16)

by Noy Holland

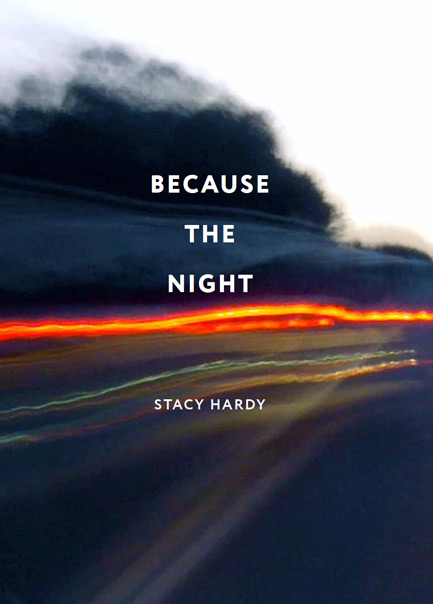

Stacy Hardy’s first collection of stories, Because the Night, is part book, part art object, an uncanny collaboration between the author and Italian photographer Mario Pischedda. Pischedda’s electrifying images serve as cover, end page, and visual contact between each story. An image precedes the title page of each story and behaves as augury for what comes next; the same image acts as a vapor trail, a sizzling remnant of the story just concluded. Thus, each photographic image illuminates the synapse between stories and does a great deal to augment the unity of the stories’ effect. The images can be soothing, though more often, fractals come to mind; cosmic fissures; lines on tarmac; lighted buttresses, blurred as if in motion; a streak of lightning; a lone headlight rending the saturated dark of the veld in which these stories are set. The images give you a feeling of place without figure or detail; they are stark, unnerving, watery, moving. They let you know you’ve arrived just a moment too late.

Arriving a moment too late is a recurrent theme among these twenty-one stories of race, power, and sexuality in contemporary South Africa. Hardy is a wizard in her evocations of absence—the vacancies between people in proximity; the longing for those we cannot reach; the estranging paralysis of witnessing the horrific. Because the Night is replete with darkly fluid narratives about people on the move—a couple on a killing spree; hitchhikers caught on the Transkei at dusk; a woman searching for her missing brother.

“You learn to live in the cracks, on the perimeter, with the need,” Hardy writes in “Conjoined.” In this story, among the longer pieces in the collection, the narrator’s search for her brother endures over the “stunned blur” of years; her search is sustained on scraps of hearsay, vague sightings, government files, “burned or stored away. Hidden.” You get used to the hunt, the sister confesses, “Adapt to it. It gives a certain rhythm to your days, fills your dreams. It’s when it ends that you’re thrown off kilter. Then the animal is suddenly real, nervous and exhausted. No longer an idea being hounded, but a dead thing living.”

A sense of abruption or stasis is prevalent among many of these stories. We see the hunter exhausted, post-road, pressed onto her back in bed, though the mind continues in its wild orbit. A woman whose breast has been amputated imagines a field of breasts planted in the ground, “A vast plain of overripe areolae sitting squat, their decapitated heads bursting under the sun.” In “A Zulu and a Zebra,” a woman in bed with her lover searches for shapes—for revelations—in the ceiling: “I squinted hard until I saw Jesus. He was ascending. I told him I hated my boyfriend. My chest went tight, my hands icy. I hadn’t realised it until I said it. Jesus couldn’t hear me. He floated benevolent on the ceiling.”

Hardy’s characters are often bound in concrete ways to the troubled landscape of contemporary South Africa, but the fantastic finds its place here, too. A prison guard required to do a body check enacts a disturbing reverse birth, entering bodily into the body of a prisoner, which breaks open into pure white. In “Squirrelling,” a woman grows adventurous while masturbating, moving from objects which remind her of her departed lover to a “tractable, rubbery” toothbrush which sprouts bristles and transforms into a squirrel: “She wanted it to squirrel inside her, to nest in her womb so she could birth an army of baby squirrels.” Soon we find her “feeding the palpitating mass into the vestibule”; she is stuffing herself, crowding out grief and desire, waiting for “the colony to panic.”

Whether flown into the fantastic or bound to the literal, Hardy’s writing issues from visceral experience, from the fusion of a playful intellect and a keen sensitivity to the coded messages the physical body sends. Appetite, she seems to say, saves us—our fascination with the possibilities of language, and with our mutable, physical selves. Violence, love, sensation, release, our confounding, insatiable needs keep us alive, make life possible.

Sex, and the power relations which inhere in sex, are central to this collection. Sex as catharsis, as blind need, as another drug among the buffet of drugs so easily found in the shadows. The drug might be dagga or a litany of suicides; Coke, Smoke, or Charlie; crystal straws or tjoef, chalk; grief or the stupor of heat. In stories like “Vanishing Point,” even landscape functions as a drug, transforming physical experience: “The heat dries her out. She is light, leather, bone, cartilage. Her wrists are wisps. The Karoo sky is endless. The reddish light of the sunset, the brown field. Occasional houses, mostly shacks, a few bodies walking through the void with bundles on their heads.”

The veld itself—vast and inhospitable—dwarfs any character moving through it, gives her nowhere and everywhere to run. Place and person, cosmos and body, can scarcely be distinguished; things coalesce and disappear and the moment of recognition is fleeting. Listen to the description of “My Nigerian Drug Dealer” in the sun on the soccer field. “I watch the sweat pour off him like an oil streak. The whites of his eyes look like shooting stars. I go home at half-time, before he sees me. That night I dream of Lagos. Streets thronging with dark shapes. In my dream it’s the end of the world. The sky is burning up and all the people are dancing.”

One can read a long way into the literature of any continent and find little which speaks so powerfully and with such candor about the life of body, the quickness of the mind to depart, as Because the Night. We cannot hope to escape, these miraculous stories insist, but let us shake the grates, feel what there is to feel, find each other, and live.