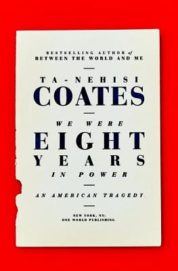

Ta-Nehisi Coates

Ta-Nehisi Coates

One World ($28)

by Chris Barsanti

Until recently, when the true desolation of the early Trump era has started metastasizing in even the most ardent optimist's heart, America had a script to use after a catastrophe. Whether a mass shooting, natural disaster, or police atrocity, each event was termed an opportunity for a "national dialogue" on guns, race, class, climate change, or what have you. Those conversations never happened because there was always another catastrophe, and in any case, the culture had mostly lost interest in the public intellectuals needed to push forward such a conversation. That changed, however, in 2014, when The Atlantic published one of the most talked-about pieces of writing in recent memory, Ta-Nehisi Coates's "The Case for Reparations." Suddenly, the country was having a conversation. And it wasn't an easy one.

When Coates published his first book, 2008's The Beautiful Struggle (Spiegel & Grau), there was no sign of the incisive political essayist he would become. A memoir about growing up in West Baltimore amidst the devastation of the crack wars and in the shadow of his ex-Black Panther father, it was lyrical and powerful, but primarily on a personal level. The larger issues that Coates would later tangle with remained largely on the sidelines. But that same year, Coates started writing for The Atlantic just as it was turning into the country's most important mainstream magazine of ideas. The results, captured in his new collection We Were Eight Years in Power, hit like a thunderclap reminder that white supremacy in America is a thing of the present, not the past.

Coates takes his title from a plaintive 1895 plea from Thomas Miller. One of the few black Representatives elected from the South after the Civil War, Miller was lamenting the painfully brief window of opportunity provided blacks in the old Confederacy before the anti-Reconstruction reactionary backlash. Coates mirrors that time frame with the eight years of the Obama presidency, tracking each year with a key Atlantic essay from that year and a running present-day commentary from Coates on himself during that year both professionally and personally. The result is not just a chronicle of the Obama years but the gestation period of a writer as he morphed from a popular blogger musing on politics, sports, and video games to perhaps America's most salient public intellectual.

The essays range from pinpoint to expansive. The First Year's "This is How We Lost to the White Man" is a portrait of both Bill Cosby's hectoring self-improvement speeches and a critique of bootstrapping harangues of black audiences dating back to Booker T. Washington. The Sixth Year's "The Case for Reparations" single-handedly reopened the previously taboo question of what America owes its black citizens for the centuries of pillage and pain. While Coates' voice develops and strengthens over the course of the book, the style remains much the same: lucid, curious, probing, and prone to a melancholic sense of tragedy. By always giving his essays a sturdy historical foundation, he keeps them from seeming like just a reaction to the newest outrage.

So even his most joyous piece, the Eighth Year's "My President Was Black"—a loose and celebratory take on the legacy of Obama, whose optimism Coates had often found unjustified—is shadowed by the institutionalized racism whose structure Coates spends much of the rest of the book tracing and explaining. The epilogue is "The First White President," an agonized exegesis of the white totalitarian assumptions at the core of the Trump presidency. On page after page, Coates fights the myopia over the "majestic tragedy" of American popular history, which so often ignores basic facts like how "racism was banditry . . . not incidental to America [but] essential to it."

It is too easy to call Coates the modern-day James Baldwin. Baldwin is the more consciously literary—Coates probably doesn't have a Giovanni's Room in him—while Coates hews to the style of a magazine writer looking for a punchy first line, like "Last summer, in Detroit's St. Paul Church of God in Christ, I watched Bill Cosby summon his inner Malcolm X" or "The first I saw Michelle Obama in the flesh, I almost took her for white." Still, Coates' second book, the meditative Between the World and Me (Spiegel & Grau, 2015), was inspired by The Fire Next Time, and both of their writings are oracular in tone and suspicious of easy solutions. When Coates writes that "there are no clean victories for black people, nor, perhaps, for any people," it's hard not to hear Baldwin's mournful moral urgency ringing through.

Coates might not be America's greatest writer. But right now, in the shadow of a resurgent white supremacy, he might be its most important.