photo by John Henry Doucette

Interviewed by William Stobb

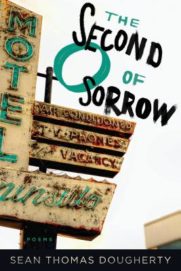

Born and raised in New York, Sean Thomas Dougherty lives with his wife and daughters in Erie, Pennsylvania. After many years as the house man at Gold Crown Billiards, Dougherty now works as a caregiver and medical technician for various disabled populations, while still writing poetry; his latest book is The Second O of Sorrow (BOA Editions, $16), which was just awarded the 2019 Paterson Prize from the Poetry Center at Passaic County Community College. Though he is published widely and has won many awards, including state arts fellowships, an appearance in Best American Poetry, and a Fulbright, the soulfulness of Dougherty’s work—a disdain for cleverness and stylization—along with his chosen subjects—people in pool halls and coal mines and karaoke bars, neighborhood kids, immigrants, anyone struggling in some way to have a voice in America—mark his work as outside the mainstream. Publisher’s Weekly describes him as “a blue-collar rust belt Romantic to his generous, enthusiastic core,” and Dorianne Laux finds Dougherty at “the gypsy punk heart of American poetry.” Widely known as an energized performer, Dougherty has been featured at The Dodge Poetry Festival, the Detroit Arts Festival, and the Old Dominion Literary Festival.

William Stobb: You’ve published more than a dozen poetry collections, and in 2014, you put out a retrospective volume, All You Ask for Is Longing: Poems 1994-2014. When we first met, you were touring in support of that book, and you felt at that time that Longing might be your last collection. But now The Second O of Sorrow has arrived, and it’s a gem—powerful, poignant, beautifully crafted. How does the book feel to you, arriving at a point in your career arc that you might not have even imagined?

Sean Thomas Dougherty: I don’t really think anymore of poetry in terms of career. I think it is because I work so far from anything literary and live far from any literary center. But in a lot of ways this book, after so many and writing for so many decades, and coming right after my Selected poems, feels like my first book—like the first 30 years of writing was practice getting down these poems. I think that was somewhat conscious, too. I was going for a leaner sort of poem, even in the longer pieces, a cutting down, getting closer to the bones of the poem, and the life.

I’m just trying to write closer to the marrow. Of course, perhaps living with so much uncertainty due to economics and disease and struggle in my family pushes one away from what is ephemeral. And so much in the literary is ephemeral. The conversations and accusations and correctness of literary folk masked as import is too often done far from the lived life and the people and places where I live. In the end, I think it was to embrace a poetics where the lived life matters:

He was so much more than flipping burgers & fries,

more than 12-hour shifts at the steel plant in Cleveland.

More than the shut-down mill in Youngstown.

More than that kid selling meth in Ashtabula.

He was every kid, every street, every silo, he was white

& black & brown & migrant kids working farms.

He was the prince of stutter-step & pause. He was the new

King.

(from “Biography of LeBron as Ohio”)

WS: I don't want to approach the situation naively, as if the poems are all directly and precisely autobiographical, but I get the sense you see your poems as a way of honoring the people you've known and things that you and they have gone through.

SD: Yes, that is perceptive. I guess it’s about getting back and closer to the lived life. Even if the poems are imagined they come out of my experience in actual places. Place figures as much as people. These cities I live or work along the lake, working class bars where I’ve play pool, diners and institutions near Erie and Cleveland. The Youngstown monologue, the Pittsburgh poems such as the Y Not Bar, which is a real joint. My dead friends Joe Rash and Frenchy who I played pool with. M who is a friend who basically went crazy after a long battle with drug addiction. Monologues that engage the opiate crisis along the lake. Lyrics of my girlfriend’s struggles with disease and addiction. Maybe it isn’t as much about honoring these people and places but about just writing to get the work down, to say they exist, they existed, they fought hard in this difficult life, continue fighting hard to survive, and that they matter. Most of this has little to do with Poetry as a business or even an art. It has more to do with poetry as something closer to breathing, something needed to keep us alive and fighting, despite the hard evidence not to.

WS: The book is full of show-stoppers; you bring intensity of emotional engagement to every poem. To me, it feels like the collection is a kind of argument for connection, for real feeling, for living in a way that’s raw and observant and vulnerable to joy and pain. I want to ask some questions about that, like isn’t that hard? And do you think it’s something that poetry has created in you? Or do you think it’s the other way around: that art comes out of you because you see clearly and feel intensely? Or am I barking up the wrong tree, here? Maybe you see this dynamic in very different terms.

WS: The book is full of show-stoppers; you bring intensity of emotional engagement to every poem. To me, it feels like the collection is a kind of argument for connection, for real feeling, for living in a way that’s raw and observant and vulnerable to joy and pain. I want to ask some questions about that, like isn’t that hard? And do you think it’s something that poetry has created in you? Or do you think it’s the other way around: that art comes out of you because you see clearly and feel intensely? Or am I barking up the wrong tree, here? Maybe you see this dynamic in very different terms.

SD: I think poetry for me has always been about ways to create some space in language that shows how in the places I live and travel and work, in places many in the culture deem difficult to live, in the smallest moments every day, people are just so damn kind and good to one another. Is it hard? I think kindness is hard. It is much easier not to be kind. It took me decades to learn how to approach anger with alternatives. Much of this I think comes out of my work as a caregiver with people who are damaged and prone to anger. When you live with this, you see how anger is so often an arbitration to what is fully human. This doesn’t mean you go through life like a little bitch and let people roll over you.

It messed me up when my friend Cody Todd, who I have inserted in quite a few poems over the years, died unexpectedly. He was the one writer I’d most want behind my back in a bar fight, and he was more than once. He was tough, and his poems were full of brilliant shards. He and I would have long debates about poetry at night online or on the phone. He and I also talked a lot about poetry as a kind of healing—the bandages of language—because most often, anger is the wrong answer. I am more interested in the small social moments where someone offers a hand. That’s probably the influence of Charles Simic; he argued to us when I was his student in the 1980s that poetry is most often about moments. I think at the core I agree with that, though I am most interested in the continuity of giving, the work unfolding as a series of moments or gestures. I am less interested in stillness or silence and more in a sort of musical notation. I am aware of the moments in real time that something emotional happens—a tone, a gesture—I try to get us there, and then when the poem unfolds that moment is hopefully recreated inside or around the reader. When poetry does this, perhaps it is narrating, or is it holding, or maybe recreating anew that moment, in language, so it does not disappear from us forever.

WS: From talking with you, and from following you on Facebook (note to reader: Sean’s an active and thoughtful social media artist, so if you enjoy his published work, I’d encourage you to connect with him online), I know that you feel at odds with a kind of poetry establishment represented by mainstream journals and academia. But I feel like your work is deeply rooted in important traditions. How do you see your work in the landscape of contemporary poetry?

SD: I used to believe in certain avant-garde tendencies in my writing, but I guess over the years I have gotten less interested in aesthetics and more concerned with questions, like Whitman: what is the grass? What words does the wind speak? What memories sweep in with the rain? Terrance Hayes’ investigative poetry fulfilled any avant-garde leanings I had, so I felt like I didn’t have to write those poems or even try to imagine them. Perhaps he did this for everyone! Because most of us can’t write poems that strong and ambitious anyways. He is also responsible for helping to bring my work to many readers. And he has done this for many writers. He reads everything. He singlehandedly brought back to readers the genius of Christopher Gilbert, whose work touched me so deeply when I was young.

Peter Conners and Sean Dougherty at Grumpy's Bar in Minneapolis

I got lucky having a publisher, BOA Editions, and an editor, Peter Conners, who continue to believe in my work. I’m not being facetious. Very few of the so called “top” journals have ever published my work and most writing programs do not even acknowledge my work exists. In this way, I am like most writers—slugging it out for decades in the trenches, sharing rejection notes and reading in small smoky places and bookstore basements over coffee.

A lot of my writing exists between genres—something not quite a poem, not quite an essay, such as the longer pieces in Second O of Sorrow. For the smaller pieces I can say for sure Sarah Freligh’s Sad Math and Julie Babcock’s Autoplay helped me to write those poems. Both authors write small tight narratives that verge on the lyric. For years I was influenced by a range of lyric writers like Lucille Clifton and Franz Wright, the performative and formal edges of Patricia Smith and the streetwise bitterness of Denis Johnson, the lyrical prose of Michael Ondaatje. Maybe in the end I am just another maudlin lyric poet? A 21st-century confessionalist? Then I think too of a poet like Malena Morling—I feel like my poems are often in conversation with hers. She should be much better known. She writes a spare often spiritual kind of poem that pulled me back to see the world behind the veil but never at the expense of this world.

And maybe that is what I am not admitting. The idea of community and shared content is very important to me despite not feeling part of the mainstream of literature. I recently completed an anthology on autism and poetry titled Alongside We Travel: Contemporary Poets on Autism, coming from New York Quarterly Books this spring. The book arose when my wife, Lisa M. Dougherty, started writing poems about our autistic daughter. I began to look around to see how others were approaching the topic. Editing this book and dealing with writers who are engaged with a topic very personal to them, I rediscovered my love for writing’s collectivist voice. Raymond Hammond is publishing the book as a fundraiser. All contributor royalties earned on sales will be donated to Sharing the Weight, a small nonprofit out of Iowa doing a simple amazing thing: gathering people together to hand sew and make weighted blankets for autistic children. Projects like this remind me that collectively poetry can do something quite important and material.

WS: I’ve been really interested in a new series of poems or prose poems that you’ve been composing, which are beginning to be published in journals, now, and which you’re posting on Facebook sometimes. You’re writing letters back to editors, responding to rejection letters, basically. Where are these new pieces coming from? Where are they headed?

SD: I experienced an amazing run of rejection with journals in the last two years. I mean the big journals almost never publish me, but this was a crazy run of like two acceptances and hundreds of rejections from journals big and small, so one day this fall I simply started to write back to my rejection letters. I think it really began by speaking back to the journal Field, which is where I first sent some of my poems over 30 years ago, who of course rejected me and have continued to religiously reject me since then. Now Field is closing shop. I outlived them, but they never published me, despite publishing the kinds of poems by people like Franz Wright that really influenced me. Too often in American culture we are taught to accept rejection without retort. Like it’s rude or presumptuous to speak back. But poetry as an art and business is steeped in endless levels of gate-keeping. I got tired of it and I became intellectually interested in the language of the rejection letter itself. As I started to write these, I also became investigative of the idea of rejection itself, across disciplines.

I think too this gets back to the earlier question about connection. After all those rejections that year, when I wrote that first response back, it was kind of funny and empathetic toward the editor. I wrote the piece on Facebook for my friends on Facebook and posted it. Writing each essay/letter on Facebook and posting it makes the project a kind of spontaneous publishing performance—maybe only 10 or 50 or whatever people see the pieces that day. I take them down afterwards. But the feedback I get has been good because one thing we all experience as artists is rejection. The pieces hope to connect across our shared failures. Social media has a kind of hatefulness to it and a kind of false pomposity, but it also has a profound possibility to help us lean against each other and help one another through hard times. This is particularly important for writers like me who do not live near the literary limelights. As the rejection project has grown, though, it is now about many kinds of rejection and acceptance. And has grown to include pieces on my wife’s long fight with illness, disability, and addiction, and explorations of my own work as a caregiver and counselor for the brain injured and disabled. The pieces are sometimes antagonistic to literary culture, but they are often empathetic, too. Editing is a tough job. We are all in some ways both submitters and gatekeepers as artists, even if only inside ourselves. Perhaps what I am writing is something not quite poetry, but a kind of “collectivist autobiography.” Here is the piece that began it all:

Dear Editors of Esteemed and tiny journals,

I know how hard you work for nothing but the love of the art, and how underappreciated you often are, so I have attached no poems for submission, thereby saving you the time of reading them, time that could be better spent reading the better poems of others, or spending time with your lover or your children, or simply sitting in the sun and maybe even writing a poem of your own, one I hope will not receive the sadness of the consequent form rejection that you would have sent if I had included my poems, poems that would have kept you from that party you were going to blow off in order to catch up on the hundreds of submissions clogging your In-Box. Now you can take that subway ride, where you can nod your head with your eyes closed and your ear plugs on, listening to that obscure composer you love of sonatas for cello and sousaphone. For the world is rather like the bell of a Sousaphone, or is it love that is the bell? The one ringing now in the high cathedral on the far side of town, where there had only been funerals for the last decade. Where the coffins are cloaked with sunflowers. The old Bulgarian women are donning their black netting. Oh Editor, where are the weddings? Who is writing, as Lorca asks, the Baptism of the new? No, my poems are not, they are old as dust, or dirt, or a broom. Too many of us are bothering you. Turn off your computer, dear editor. There is honey waiting to be spooned in your tea. There is poppyseed cake. Look out the window. There is wild thyme and fennel.

Sincerely,

WS: Do you see a book of these happening, maybe? I feel like it could be a really liberating read for a lot of writers.

SD: There is a manuscript of these. I save them. I’ve written fast in the last months between working my night shift job and living, and I probably have about 120 double spaced pages so far. It’s not really a book of poems though. I think of them closer to essays. Or simply a book of letters. I’ve always been interested in work that is not quite—not quite a poem, not quite an essay. Can a letter be a poem and a poem be something as intimate as a letter? Remember what O’Hara and Hugo said to us decades ago? That intimate detail of reading a poem as a letter. A lot of new media has this kind of tone. Instagram poems as memes, whether you love them or hate them, are in fact sorts of letters, electronic posters; they harken back to the surrealist and dadaist use of media. They exist as something that crosses into different types of textuality that are more than literary. They borrow from these populist forms. I do not engage in Instagram and Twitter simply because I work long hours. But I applaud these new forms of writing. Perhaps we never grow far, despite the decades, from our formative teachers, and this rejection project feels like a book another of my old professors, Michael Martone, might have written. I can feel the influence of his “Contributor’s Note” essays and stories as I examine and appropriate the language of acceptance and rejection notes. But to be honest, maybe the book should never be published—maybe it should just continue to be written, sent out, and rejected. For the real acceptance of the work and of each other (and maybe this is just the Jewish mystic in my blood) is the breathing and the saying, the making and sharing of them. It is a book that only exists by someone saying No. I wonder, William, if that is what all literature, all poetry is? To write back against this world that says shut up, you are less than, you do not matter, you are poor, you are different. You are damaged. In the end we all die. We are all failures. We are all witnesses for each other.

NOTE: Since the recording of this interview, Sean’s “Dear Editor” series has been contracted for publication by New York Quarterly Books, and is forthcoming in October 2019 under the title All My People Are Elegies.