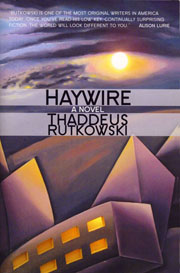

HAYWIRE

HAYWIRE

Thaddeus Rutkowski

Starcherone Books ($18)

by Vincent Czyz

Faulkner’s now-famous quip about Ernest Hemingway—“he has never been known to use a word that might send a reader to the dictionary”—was just as famously rebutted by Papa: “Poor Faulkner. Does he really think big emotions come from big words?” In Thaddeus Rutkowski’s Haywire we get the worst of both worlds: there is nary a complex sentence in this novel, and emotions are just as rare—as least for all but the last third of the book. The book’s nameless narrator—the only constant character in the novel—flounders aimlessly in the first 200 or so pages, and never cries or rejoices, never gets angry or frustrated, never laughs or anguishes over anything, turning what would have been better off as memoir into bland fiction.

The back cover claims that Haywire is “composed of 49 flash stories,” which recount the experiences of the unnamed narrator—whom I’ll call Thad for convenience—following him from childhood to maturity. The novel starts out in rural America, covers college, and finishes up in a “big city.” For reasons I can’t fathom, Rutkowski avoids names as much as possible, so we don’t know where Thad grew up (although we can guess it’s Pennsylvania because that’s where Rutkowski grew up). Nor do we know the big city (although we can guess it’s New York because that’s where Rutkowski ended up). Like the author, Thad is also a writer who sometimes paints, and, has a Polish-American father and a Chinese mother.

Unfortunately, the “flash stories” are not stories at all; they simply record, like blog entries, what happened on a given day or over the course of several days. Worse, a good number of them read like they were written by someone who hasn’t yet reached his teens: “On a chilly day, our father decided it was time to gather the butternuts that had fallen from the tree in our yard. He told my brother and sister and me to put on gloves and old shoes and follow him outside.”

The prose drones on in this monotone for virtually the entire book. There is no narrative arc to the individual stories—which are in fact merely incidents—and none overall other than simple chronology. Thad does not have a very interesting life. Here’s one of the highlights of his childhood: “In the house, I played loud music on my father’s turntable . . . The sound might have carried down the street to neighbor’s houses, or it might not have. I didn’t check. I just listened to the notes blasting over me. Some songs made me happy, while others made me sad. I played both kinds.”

The “action,” such as it is, takes place in mostly undescribed space and is performed by faceless characters, generally referred to as “my friend,” “my siblings,” “my spouse,” etc. When Thad goes to college, we never find out his major and although we see him in a couple of classes, we have no idea whether or not he likes them. He falls into the habit of smoking pot, takes his habit with him after he graduates, and eventually goes to rehab. Finally, toward the end of the book, his half-hearted search for someone to tie up emerges as a bonafide obsession, but even then his desires are handled clownishly:

I had acquired my first such implement [a horse paddle] at a harness shop. I grew up among plain folk, farmers mostly, and I bugged out when I saw that they used buggy whips, riding crops and horse paddles in their daily lives. In short order I learned to whip myself into a lather. This froth extended to my monkey [penis], which was always ready to get lathered up.

Pleased with his metaphor, he presses on: “When excited, my monkey was a harsh master. He was King Dong . . . I let my chimp go ape.”

Eye-rollers such as the juvenilia above seem to constitute Rutkowski’s idea of how to break up the tedium of the writing. He even manages to make an acid trip seem dull: “I looked through the mist at a traffic light half a block away. The incandescent colors, changing from green to yellow to red and back to green, fascinated me. Raindrops sparkled as they fell past the disks of light. I stood there for what could have been an hour, watching.”

In the end, Haywire comes off as a thinly disguised memoir composed of writing that is pathologically lazy. Incidents—not “stories”—don’t particularly end; they just drop off like wooden soldiers marching over a precipice. Although Rutkowski grew up before the Internet came into vogue, one can’t help but wonder if the blog wasn’t his model here, as there are many parallels: something is deemed worthy of being recorded simply because it happened to the blogger; an effort is made to make everything bite-size; there’s nothing distinctive enough in the writing to call a voice; there’s no attempt to refine raw material. (I am speaking generally, of course; many blogs have distinctive voices that display wit, irony, and humor, and some are downright eloquent.)

As fiction, Haywire is a dismal failure. As memoir, it might have amounted to something if only the author had been as interested in his material as he wants us to be.

Click here for another review of this title

Click here to purchase this book at your local independent bookstore

Rain Taxi Online Edition, Summer 2011 | © Rain Taxi, Inc. 2011