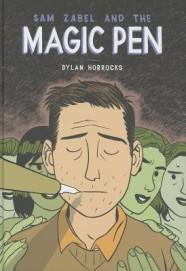

Sam Zabel and the Magic Pen

Dylan Horrocks

Fantagraphics ($29.99)

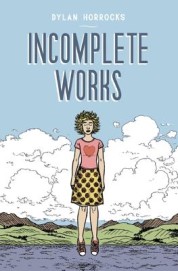

Incomplete Works

Dylan Horrocks

Victoria University Press ($19.99)

by Stephen Burt

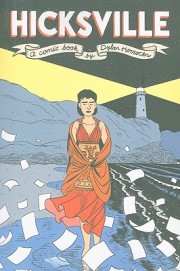

If you want a graphic novel—no, let’s call them comics—if you want a book-length comic that’s wry and thoughtful and endlessly suggestive about the theory and practice of making comics; about the long international arc of comics history, which hasn’t bent all the way towards justice for creators (especially not creators from decades ago); about how comics fans misunderstand comics makers, and vice versa; about what separated (circa 1995) comic strips from comic books, superhero comics from other genres, mainstream comics from independent creations, loving caricature from satire from heightened realism; about (not least) the history of New Zealand: if you want all those things, and if you like comics, or novels, or films, that change their style and genre with every chapter, so that to follow the plot to the end you have to keep changing the habits by which you read—if you want all those things, you probably need, and you may already have read, Dylan Horrocks’s black and white masterpiece Hicksville.

If you want a graphic novel—no, let’s call them comics—if you want a book-length comic that’s wry and thoughtful and endlessly suggestive about the theory and practice of making comics; about the long international arc of comics history, which hasn’t bent all the way towards justice for creators (especially not creators from decades ago); about how comics fans misunderstand comics makers, and vice versa; about what separated (circa 1995) comic strips from comic books, superhero comics from other genres, mainstream comics from independent creations, loving caricature from satire from heightened realism; about (not least) the history of New Zealand: if you want all those things, and if you like comics, or novels, or films, that change their style and genre with every chapter, so that to follow the plot to the end you have to keep changing the habits by which you read—if you want all those things, you probably need, and you may already have read, Dylan Horrocks’s black and white masterpiece Hicksville.

Self-published chapter by chapter in Horrocks’s zines, collected in 1998 and re-published for North America in 2001, Hicksville told the intricately intertwined stories of the NZ indie comics maker Sam Zabel (a slightly bedraggled stand-in for Horrocks himself); the NZ-born, Stan Lee-like industry titan Dick Burger; and the American fanboy Leonard Batts, who comes to the village of Hicksville to research Burger’s life and discovers the secret history of comics—and maybe also of New Zealand—instead. It could be the Cloud Atlas of comics, unless it’s comics’ version of To the Lighthouse instead, being a meditation on travel, grief, familial love, and aesthetic success—there’s even a climactic lighthouse. It was, for nearly twenty years, the only thing written and drawn by Horrocks long enough to be a proper book.

But no more. Sam Zabel and the Magic Pen is, like Hicksville, a meta-comic, a story about what it means to construct and share fictions made out of panels, captions, pictures and words; like Hicksville, it presents a secret history of what comics could or should have been. It follows Sam much more closely than Hicksville did; it’s a simpler story, easier to follow, with higher production values (full color, for example), and a line that’s more consistent, cleaner, more “professional,” too. Older, married, a dad, not so much anxious or unsettled as anomic and depressed, Sam earns a living by writing the once majestic superhero comic Lady Night, whose current version—boobs, boots, blades, and nonstop battles—he abhors (Horrocks himself wrote Batgirl in the 2000s). Unable to work, Sam escapes into erotic visions; there he encounters Lady Night herself, who tells him “You’re a hack. Get used to it,” then disrobes and invites him to “make me your fantasy, Sam.”

what comics could or should have been. It follows Sam much more closely than Hicksville did; it’s a simpler story, easier to follow, with higher production values (full color, for example), and a line that’s more consistent, cleaner, more “professional,” too. Older, married, a dad, not so much anxious or unsettled as anomic and depressed, Sam earns a living by writing the once majestic superhero comic Lady Night, whose current version—boobs, boots, blades, and nonstop battles—he abhors (Horrocks himself wrote Batgirl in the 2000s). Unable to work, Sam escapes into erotic visions; there he encounters Lady Night herself, who tells him “You’re a hack. Get used to it,” then disrobes and invites him to “make me your fantasy, Sam.”

Is it OK to use comics as wish-fulfillment fantasy? If it is OK, what do we do with the misogyny, and the power-worship, and the chauvinism, that turn up all over the history of comics (and, for that matter, in real people’s sexual fantasies)? If it’s not OK, why won’t those fantasies go away? They’re old questions, because they’re hard questions, and they come up in almost any art; but they’re especially pertinent to comics, because so many comics—so many good ones—have been either straight male “power fantasies” (to use Scott McCloud’s disapproving term), or reactions against power fantasies, “boring comics about my stupid miserable life that nobody wants to read,” as Sam puts it (he used to write those too).

Rather than writing either, Horrocks writes both, investigating the human psyche’s need to escape by exploring multiple escape routes. That’s what Sam, and Sam’s feisty feminist sidekicks Alice (a smiling twenty-something con-going fan) and Miki (a rocket-booted manga heroine) literally do, thanks to the Magic Pen. If you blow or sneeze on a comic drawn with that immemorial pen (as Miki explains), you enter the comic: “all you have to do is give it the breath of life.” If, for example, you gesundheit over The King of Mars, by the (made-up) 1930s-40s NZ writer Evan Rice, you will end up on Rice’s Edgar-Rice-Burroughs-esque male-fantasy Mars. “How come the men here are all bright red, but the girls are green?” a spaceman asks; the answer: “Women are from Venus and men are from Mars, of course!” Sam meets Miki on Mars, and Alice on Venus, and Sam Zabel becomes an attractively drawn meta-adventure, with excursions into several other comics’ secondary worlds.

If cartoonists cannot be “God-kings” (Rice’s status on Mars), how should they see their creations? “What if the whole point of fantasy is to go beyond the boundaries of the real?” If comics aren’t good for that, what are they good for? They’re questions you can give almost any comic, from Little Nemo in Slumberland to Hothead Paisan to Secret Wars, and Horrocks has clearly read a lot of comics: the more comics you know, the more references you’ll see in this one, to whole genres (including Japanese tentacle porn: don’t say we didn’t warn you) as well as to individual works. When we see Rice at a drawing board, Rice himself looks like Archie from Archie, but the panel looks like a famous page from Maus.

Sam Zabel is, mostly, a thoughtful delight, a celebration of Horrocks’s chosen medium, with powerful supporting characters helpfully present to save the day and to articulate running feminist commentary while a sad-sack viewpoint character—white, male, educated, and middle-class—escapes into one after another creation. To praise it that way is also to make clear its limits. Sam Zabel can seem like the Woody Allen of comics, albeit with better hair; his adventures with the Magic Pen are his Midnight in Paris, his Purple Rose of Cairo, his fifty-minute hour on the couch.

Sam may not be able to get outside his own head, but at least he knows it’s not the only head around. To re-read Sam Zabel and the Magic Pen is to see an argument that comics will get better—aesthetically, politically, intellectually—the more they get made by people with different experiences, and therefore different fantasies, from the people (people like Horrocks, for instance) who have been likely to write them before. Your fantasies also depend on what your deepest feelings tell you that you need. For Rice, it’s illegal, impossible, or inadvisable sex, with busty green ladies; for Zabel, it’s a chance at real invention, and maybe the love of female fans. For infantry at Passchendaele, it’s not being gassed. And in order to make new comics—that’s the point Alice keeps making, with some glee—you have to find some way to like some of the old ones. “I’ve learned to take those imaginary worlds and make them my own,” Alice says, “subverting them to serve my fantasies.” [162] As she speaks, she’s surrounded by soaring superheroes, one of whom may have just let a bird poop on Sam’s head.

Sam Zabel and the Magic Pen is terrific for what it is, but it’s also less complicated, less challenging—less indie, if you will—than Hicksville. As close to Sam’s perspective as it remains, it may get your hackles up if you are looking for both a new, and a thorough, critique of gender, exoticism, power and politics in comics, even though the volume wants, with an aching honesty, to join that critique.

What it can’t do—because it’s drawn so accessibly, and so consistently—is demonstrate all Horrocks’s powers. For that, there’s Incomplete Works, a selection of Horrocks’s briefer comics—some one page, some long enough to be short stories—made between 1986 and 2012, originally printed by Victoria University Press of Wellington, NZ, and soon available in a North American edition courtesy of Alternative Comics. In my ideal world all comics readers would own Incomplete Works, having devoured either Hicksville or Sam Zabel first. They would then recognize outtakes and dry runs for scenes from the longer works, such as new adventures for the ridiculous M&M-shaped jokesters Moxie and Toxie (whom Sam draws), as well as early, Morrissey-shaped versions of Sam. Horrocks’s readers would—in this ideal world—recognize homages to, and jokes about, the makers of international repertoire (Winsor McCay, George Herriman), and they would learn about real giants of Kiwi comics, such as Barry Linton, subject of an attractive eleven-page nonfiction feature profile in comics form.

What it can’t do—because it’s drawn so accessibly, and so consistently—is demonstrate all Horrocks’s powers. For that, there’s Incomplete Works, a selection of Horrocks’s briefer comics—some one page, some long enough to be short stories—made between 1986 and 2012, originally printed by Victoria University Press of Wellington, NZ, and soon available in a North American edition courtesy of Alternative Comics. In my ideal world all comics readers would own Incomplete Works, having devoured either Hicksville or Sam Zabel first. They would then recognize outtakes and dry runs for scenes from the longer works, such as new adventures for the ridiculous M&M-shaped jokesters Moxie and Toxie (whom Sam draws), as well as early, Morrissey-shaped versions of Sam. Horrocks’s readers would—in this ideal world—recognize homages to, and jokes about, the makers of international repertoire (Winsor McCay, George Herriman), and they would learn about real giants of Kiwi comics, such as Barry Linton, subject of an attractive eleven-page nonfiction feature profile in comics form.

Those readers would see, within Incomplete Works, fiction and nonfiction, clean exposition and teasingly used blank space; they would come to see comics—and maybe all art forms—as kinds of collaboration among the artist, the artist’s material, and the reference points, styles, precursors, the artist has known. Best of all, they would see the comics Horrocks drew on blank postcards in the 1990s, when he was visiting Europe or living in England, elegantly spare semi-pro affairs that limn his loneliness and his youthful confusion while also demonstrating the points that Horrocks has since made in essays about comics theory, such as “Inventing Comics” (a response to McCloud) and “The Perfect Planet: Comics, Games and World-Building” (in part a defense of Dungeons & Dragons). You can read these essays, and view other short form comics, on Horrocks’s site, www.hicksville.co.nz. In my ideal world, you would read them all. I don’t live in that world—no one lives in their ideal world, which is one of the points that Sam Zabel makes. But I can get us that much closer to it if I can get you to read Horrocks’s books.