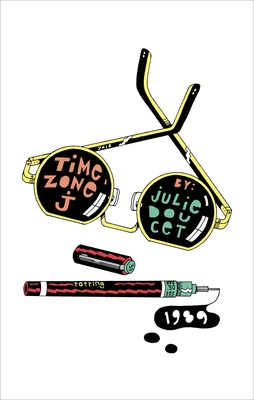

Julie Doucet

Drawn & Quarterly ($29.95)

by Steve Matuszak

“I had vowed never to draw myself again,” Julie Doucet tells readers at the beginning of Time Zone J, her first graphic novel since her comics diary 365 Days was published in 2006. Time Zone J seems to be an emphatic repudiation of that vow, since Doucet’s face appears on practically every page, the self-portraits piling up like images from a stuttering video. But the Julie Doucet who appears in these pages is like none we’ve seen in her work before. Gone is the cartoony persona from her earlier comics, a character who represented the young cartoonist and her dreams, desires, hopes, and fears. In Time Zone J, she is replaced by a figure who, while still exaggerated, is rendered with a more realistic drawing technique and is largely limited to narrating the story rather than participating in it. The immediate effect is that this new “Julie Doucet” is at once more and less real than her earlier incarnation, playing out Doucet’s antipathy toward autobiography and her ongoing interrogation of visual and verbal representation—especially as they relate to memory, which sets the novel in motion, and to desire, its beating heart.

That Time Zone J should be seen as an intentional break from the comics that established Doucet as one of the most important cartoonists of her generation is established before the book begins. In an introductory note, Doucet instructs readers to read each page “from bottom to top,” essentially upending the traditional Euro-American comics page. Even the notion of the page itself is undermined. Images bleed over the edges of the book’s uncut pages, suggesting that the entire novel is one long page that could be unfurled if one undid the book’s binding. Gone too is the notion of comics panels, either explicit or implied. Instead, the reader encounters reiterations of Doucet’s face, sometimes with shoulders visible, at other times revealing a bit more of her body, within a collage of text, word balloons, and random people, animals, objects, doodles, and abstract geometrical patterns that have little to do with the text. A character might crystallize from a dream, as when a woman smoking a cigar appears alongside Doucet, or when Johnny Rotten makes a memorable appearance as Doucet describes the dream in which he has a key role. But those characters are rare and seem to have no more importance than the figures surrounding them.

Admittedly, it is disorienting. Adding to the disorientation, the book refuses at first to coalesce around a discernible structure—narrative or otherwise. The overlapping images do not repeat, except for the ones of Doucet. And the words articulate disconnected statements and ideas, like those passing through the mind of someone just waking up, phrases rising to the surface in word balloons and popping like soda bubbles. Eventually, after a few pages, short recitations of dreams cohere from out of the chaos, vanishing as suddenly as they appear. These shards of story plant the seeds for a more extended autobiographical narrative of Doucet’s youthful friendship with two men that collapsed after she’d initiated an unsuccessful affair with one of them. That narrative is the prelude—or, as Doucet utters in the book, a “prolegomena,” which she defines as “a critical or discursive introduction to a book or: goiter of the Alps”—to the story that takes up the remainder of Time Zone J: a romance, or more accurately an amour fou, with a Frenchman that began in 1989 over correspondence about Doucet’s zine Dirty Plotte (which transformed within a couple years into the bestselling comic book of the same name).

The story is both heady and frightening. The Frenchman, a young conscript in the 3rd Regiment of Hussars in the French army, writes frequent letters to Doucet, sometimes several a day, that become increasingly romantic and erotic; Doucet does not quite keep pace, but definitely stays in the game. In time, an opportunity arises for them to meet in France where, after a few awkward phone calls and encounters, they consummate their relationship, Gothically, in a cemetery. At times throughout their days together, Doucet fears for her safety—what does she really know about this guy? Unfortunately, though she is able to quell her fears in the moment, they never quite abate over time.

In a way, the representational strategy of Time Zone J enacts its themes. By ridding the graphic novel of panels, pages, and identifiable characters, Doucet strips Time Zone J of time, much as those who are madly in love occupy a place that feels outside of time. In fact, the novel gets its title from one of the young man’s letters during a period when he is learning morse code: “julie [sic] everything reminds me of you: Earth is divided into 25 time zones, each being presented by a letter. only j is not used.” But if, in this metaphor, Julie, the object of his love, is timeless, so too are the dead, an insidious connection reminiscent of German Romanticism’s Liebestod, an association wholly in line with this young man’s dark intensity. Moreover, for those who fear impending violence, as Doucet does at moments throughout her relationship with the hussar, by trying to anticipate its unexpected blossoming in the placidity of one’s daily routines, each second can seem an eternity—minutes, hours, and days dragging out interminably.

Doucet’s approach in Time Zone J also points to a discomfort with autobiography that she expressed in a 2010 interview for Ladygunn magazine: “For me autobiography is a disease.” As she contemplated the possibility of returning to comics in a 2017 interview with cultural critic Anne Elizabeth Moore, Doucet pronounced, “I wouldn’t do autobiography. Never again. Impossible.” One senses that aversion in the book’s form, sapping the material of some of its strength. Granted, by not depicting the events from the past that the book recounts, by not giving the young man and the young Julie Doucet pictorial form, by not animating them through the sequential storytelling of comics, Doucet doesn’t misrepresent them. They do not become subsumed, however subtly, to her current desires and thoughts, which remain clearly delegated, however parsimoniously, to the older Julie Doucet who is narrating the novel, somebody who remembers the events she’s telling us and comments on them from a distance. In avoiding this question of representational truth, however, Doucet misses out on the aliveness of representation itself, a quality that pulsed in her earlier comics. Then, her imagination played over the objects of her attention, transforming them by rendering them in pictures and narrative, creating meaning and pleasure by how they were presented, how they were brought to life for readers. For all the pleasures that Time Zone J offers, it leaves us with a lingering impression more of Doucet’s memory and less of her beating heart.

Click here to purchase this book at your local independent bookstore:

Rain Taxi Online Edition Fall 2022 | © Rain Taxi, Inc. 2022