Lindsey A. Freeman

Lindsey A. Freeman

Redwood Press ($18)

by Will Wlizlo

Oak Ridge is a small city like many other small cities and, at the same time, a place with few parallels. Its mazy streets are dotted with anodyne pre-fab homes like so many post-war communities, yet the sleepy town just west of Knoxville, Tennessee, has a humming, volatile core. It was built from the dirt up as a primary component of the Manhattan Project; the nearby Oak Ridge National Laboratory and Y-12 National Security Complex provided much of the research and fissile material used in the atomic bombs dropped on Japan. It’s also where Lindsey Freeman grew up.

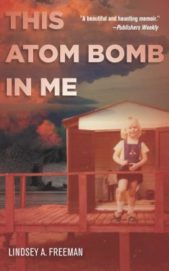

In This Atom Bomb in Me, Freeman describes coming of age in and around Oak Ridge, and how she carries her “atomic childhood” within herself. “I felt animated by a kind of power coming from Oak Ridge and my connection to the Atomic City,” she writes. “I often felt like the acorn inside the twirling atom, the city’s totem—something ordinary made extraordinary through a field of power.” Both the mundane and the mysterious irradiate this slim memoir, which builds into something more than just the remembrance of a uniquely situated adolescence in Reagan’s America. In addition to an idiosyncratic consideration of memory and belonging, This Atom Bomb in Me offers a poetic exploration of how culture and identity synthesize each other.

Freeman lived in Oak Ridge for a few months, but her parents moved to the nearby working-class city of Morristown while she was still an infant. She visited often to see her grandparents, who still lived there, and many of Freeman’s sharpest memories come from her summer vacations and car trips between home and Oak Ridge. Her remembrances from that time have a comic uncanniness, a sense of something sinister hidden within the goofy scenes of childhood. Freeman’s memories of playing tricks on the Russian spies who drove around Oak Ridge, finding rickety barns that concealed secret laboratories, and memorizing the lyrics to R.E.M.’s “It’s the End of the World as We Know It (And I Feel Fine)” all take on a darker cast when considering the historic context of the end of the Cold War. And, of course, there are memories unambiguously shot through with radioactive material. “All the autumns of my youth,” she writes, “we played soccer by a sweet little creek that was so gentle we never thought to ask if the water was laced with strontium-90 or toxic mercury, by-products of the city’s nuclear industries.”

This Atom Bomb in Me jumps rapidly between valences, and Freeman unpacks how the local manifestations of the nuclear moment and her perception of broader global currents orbit each other. For example, living near Oak Ridge felt more precarious after seeing television footage of Pripyat, a city in the former U.S.S.R. most famous for being downwind of the Chernobyl nuclear reactor. “Nearly nine tons of radioactive material was thrown into the air, creating a black plume of radioactive smoke that smothered the city of Pripyat,” she recalls. “The entire city was evacuated. It was hard to wrap my head around the fact that a city could be there one day and all its inhabitants gone the next. It was even more frightening because this was a nuclear city full of experts—scientists and engineers—and something had gone horribly wrong.” One gets the impression that, after a lifelong buildup of atomic culture in her bones, the footage of the Chernobyl reactor meltdown was among the most devastating images of Freeman’s adolescence.

Images, both devastating and nostalgic, are a key component of This Atom Bomb in Me. As Freeman flips through her memories, the memoir settles into a scrapbook-like form. The text is broken into eighty-two short sections, and the pages are filled in with visual ephemera, including family photos, historic images of Oak Ridge, snapshots of pop culture artifacts, and artworks. Reading feels like dipping in and out of a precociously curated diary.

In this way, Freeman creates what she might call a “sensorium.” By gathering things she touched, smelled, heard, saw, and ate in youth—there’s a surprisingly introspective tangent about Atomic Fireball candies toward the book’s conclusion—she conveys how a local culture fused to atomic progress can mutate both matter and spirit. “It radiates throughout the city,” she says of the subliminal atomic hum of Oak Ridge, “[it] goes underground, swims and dives through rivers and tributaries, and ignores boundaries and barriers of every stripe. I carry it in my own body. It is both outside and inside, material and immaterial, pulsing and still.”

But after immersing oneself in her sensorium, can we see, hear, taste, smell, and feel the world of an atomic child in Oak Ridge? As a researcher and professor of sociology, Freeman is aware of the challenges in understanding cultures and social narratives. To aid her introspective rumination, she treats readers to a primer on some of the thinkers who’ve puzzled over questions of authentic self-understanding. Roland Barthes’s Empire of Signs is the most prominent critical reference. Barthes’s primary anecdote in that book is the fable of Little Red Riding Hood, who is famously eaten by a wolf disguised as her grandmother. To fairly judge the place or context in which we reside, Barthes contends, is similar to the predicament of Little Red Riding Hood “trying to destroy the wolf by lodging comfortably in its gullet.” By refashioning the wolf’s gullet from the commercial clutter of mid-century America and exploring the cultural vibrations of the subsequent generation, This Atom Bomb in Me deflects some of our insights into the more essential ways that family, community, and the broader experience of childhood in the Atomic City shaped Freeman. Yet at the same time it also highlights the pervasive leeching of a culture into its citizenry. This tension remains satisfying and provocative throughout the memoir.

We’re left with a model of the author that resembles the structure of an atom. Her revealed core has two parts: a happy-go-lucky kid and a cool, neutral academic. She also presents moving, interrelated flashes of her life—the stories, remembrances, artifacts, trivia, and scholarship—that revolve around her character and keep the whole narrative in balance. These pieces are like the protons, neutrons, and electrons of Lindsay A. Freeman. Eighty-two textual scraps circumnavigate and protect the core; the loops of their meanings create both a boundary and a mechanism to communicate her story. And so, if the comparison may continue, This Atom Bomb in Me is like the chemical element lead, with its eighty-two protons, neutrons, and electrons. Lead, unlike plutonium or uranium, doesn’t have an explosive history. But, depending on how the element is used, its toxic nature can manifest in unexpected places—or its malleable structure can contain the malevolence of radiation.