by Benjamin P. Davis

by Benjamin P. Davis

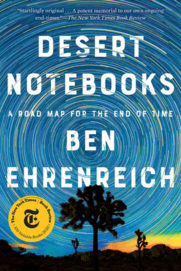

The provocative subtitle of Ben Ehrenreich’s Desert Notebooks: A Road Map for the End of Time (Counterpoint Press, $26) suggests we are on a journey through an era that includes, as the jacket copy elaborates, “the pasts we have erased and paved over” and “the future we have no choice but to build.” This interview is both an elaboration on where this road map might take us and a snapshot of the midpoint between the aforementioned past and future: “this anxious present.”

Compelled by his call for writing that “takes sides” in this context, I reached out to Ehrenreich in October 2020. I researched and wrote my questions while quarantining in an airport hotel outside of Toronto, having begun my move to Canada’s most populous city for an academic appointment. While Ehrenreich was writing his responses, he was quarantining in a studio apartment in San Francisco after having flown across the country from Washington, D.C.

As fate would have it, we finalized the interview in November, in the wake of the Biden-Harris victory. “Covid cases were rising exponentially everywhere and Donald Trump was still trying to get the election overthrown,” Ehrenreich wrote to me. “I was, as usual, cycling through too many books: Sven Lindqvist's Exterminate All the Brutes, Kirkpatrick Sale's After Eden, Andrew Lipman's The Saltwater Frontier, Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing's The Mushroom at the End of the World, Frank Snowden's Epidemics and Society, and Anna Kavan's Ice.”

Benjamin P. Davis: You raise a question many writers are thinking about these days: “Is it possible to write without plundering, to leave something behind that is true? I don’t mean writing that is innocent. Such a script could have no meaning. I mean writing that takes sides, without compromise or dissemblance or theft, that stands not only with the living but with the dead, with everyone and everything that this society is working to erase?” What side are you on in Desert Notebooks, and how do you think about taking a stand in writing?

Ben Ehrenreich: Well, all writing takes a side, doesn’t it? The question is whether the writer acknowledges it or not. At certain points in history something more is needful. We are at one of those points, when everyone, writers included, has to decide with whom they are willing to stand arm in arm, and with whom they are not. The not-so-secret path to success in American letters is to stand with the powerful. You can be challenging, brash, obnoxious, even offensive, so long as you ask no questions that will fundamentally upset the status quo. But the status quo—and really by that I mean capitalism—is no longer simply unjust or oppressive. It’s killing us, all of us who share the planet. A few people are profiting from it; most of us are facing unending insecurity and bottomless loss. So, to me the sides are clear.

BD: I felt that there were two strong pushes in Desert Notebooks. The first is about slowing down and positioning ourselves within the worlds that surround us. You write about how orienting yourself in the desert with another demonstrates “how distracted we had been.” The second is a call to radical politics, seen in your grandfather who “read Marx and came to believe in the possibility of another world, a better one than this.” In my experience, these are often conflicting trajectories: rent a cabin to write or show up in the streets; slow down or mobilize; disavow the news or read everything you can. The form of the book itself reflects this tension, often cutting from myths in societies to news you saw online to walks in the desert. How do you think about navigating between challenging distraction and staying informed? I’m interested in this question because books with a similar environmental push and in a similar genre, such as Elizabeth Kolbert’s Field Notes from a Catastrophe, often have the unfortunate effect of suggesting that the real environmentalists travel to all of the hot spots rather than engage in local action.

BD: I felt that there were two strong pushes in Desert Notebooks. The first is about slowing down and positioning ourselves within the worlds that surround us. You write about how orienting yourself in the desert with another demonstrates “how distracted we had been.” The second is a call to radical politics, seen in your grandfather who “read Marx and came to believe in the possibility of another world, a better one than this.” In my experience, these are often conflicting trajectories: rent a cabin to write or show up in the streets; slow down or mobilize; disavow the news or read everything you can. The form of the book itself reflects this tension, often cutting from myths in societies to news you saw online to walks in the desert. How do you think about navigating between challenging distraction and staying informed? I’m interested in this question because books with a similar environmental push and in a similar genre, such as Elizabeth Kolbert’s Field Notes from a Catastrophe, often have the unfortunate effect of suggesting that the real environmentalists travel to all of the hot spots rather than engage in local action.

BE: That’s a tension I feel all the time. I haven’t been back to the Mojave for more than a year, and however much I am plugged in to the people and events around me, I know there’s a different and vital connection that I’m missing. I rarely know what phase the moon is in anymore. I don’t get to see the stars. For a while I really mourned that. But I know that it was an incredible luxury to be able to slow down like that and get attuned to the rhythms of the non-human world. Cities are so fast. It’s very easy to get caught up in bullshit. But ultimately, I think the tension is a false one. In the cities, in the thick of things, you just have to do some extra work to tune in to the thrum of life without getting your head whipped around too much. I think that’s what my grandfather was talking about. Except for a brief spell in New York, he lived in Philadelphia all his life. I can’t even imagine him out in the country. He would have hated the desert. But in revolutionary politics and in scientific inquiry alike he found that same sense of radical connectedness that I found there.

BD: My reading of Desert Notebooks coincided with my moving to Canada for a new job. What kept me coming back to the book was how you take on some of the most salient and fundamental questions of our time: not just migration and environmental destruction, but the concepts of time and place that elevate one story about “political maturity” and economic growth while allowing many of us “to forget that there were always other roads, other ways to see things, other stories, other routes.” Why do many of us “forget” about other paths?

BE: The easy answer is that they’re erased so effectively that most of us are never even exposed to them. We have to seek them out. The stories that we grow up with, the grand narratives of progress and modernity, of “Western Civilization” on the rise, are entirely ideological. They work to celebrate and legitimate a certain vision of the current order. The stories that challenge that order get marginalized and erased. It’s like those lines at immigration: some people are allowed in and others are turned away. But being turned away is not a passive thing. They don’t just say no and then you disappear in the breeze. I don’t know the Canadian system, but in the U.S. people who are turned away are frequently detained, which is to say imprisoned, and deported or otherwise ejected. It is a coercive and at times lethal process. The erasures that allow a single, homogeneous narrative to dominate are similarly violent.

BD: Let’s say our readers are interested in these “other stories, other routes.” Re-imagining is profoundly difficult. I was raised in a tradition that sees a forest as decoratively beautiful as well as a potential site of revenue. And although I have learned from people who imagine the world very differently—such as the Xukuru people who live in what is now called Brazil and who continue to be leaders in important struggles for human rights—I have to own up to the fact that my understanding of a tree, not to mention of concepts like time, is very different from a Xukuru’s understanding. So what if we extend the question you pose about writing to knowledge practices more generally: how do we learn without plundering?

BE: It’s not easy. Because you’re talking about a way of learning that isn’t just about assimilating information or digesting new facts, but of more fundamentally altering our subject positions, opening them to other realities and forms of life. And I don’t think that kind of transformation can only come about through cultural appropriation, through the colonialist power relations that got us here. If we want to start thinking about trees, for instance, in a way that allows them a certain diffuse and distinctly nonhuman form of subjectivity, not as resources but as beings, we don’t have to look that far. Peter Wohlleben’s The Hidden Life of Trees (Greystone Books, 2016) was a bestseller in the U.S. and in Europe, and in an abstract way it does some of that work for you. Or take the anthropologist Eduardo Kohn’s How Forests Think (University of California Press, 2013), which draws on Kohn’s fieldwork with the Runa people of the Ecuadorean Amazon but also on the very American philosopher Charles Sanders Peirce, who allows Kohn a broader way of conceiving language and selfhood, one that isn’t limited to human beings. I want to suggest that the erasures were never quite complete, and even within European and North American rationalist traditions, or on their margins anyway, there is plenty of room for a major epistemological pivot. There always was, though you often have to dig a bit to find it.

BD: Part of re-imagining is re-learning our emotions, our expressions of being with others in many worlds. You reflect history’s lesson that “the joy that I take from this land has been contingent on the destruction of someone else’s world.” Where does this reflection push you—to projects of corrective justice? Is part of the role of literature, for you, in raising consciousness around these rectifying efforts?

BE: I’ve been a journalist for most of my adult life, and I’ve tried hard to use whatever platform I have to tell stories that otherwise get silenced, whether in Palestine or in Somalia or in immigration prisons in the U.S. I don’t have much faith anymore in the liberal model that suggests that by documenting injustices we will inspire people to act to end them—it’s rarely so easy—but I do believe that erasures and lies throw the world off balance and that it is the work of the writer to fight to tilt it back. That sounds quite mystical, but I mean it very concretely.

BD: You return in this book to your time in Ramallah under conditions of war, when “time no longer proceeded evenly and sequentially, but according to a strange logic of dread.” You connect this feeling to the years “since the Rhino’s election . . . Time appears to fall apart.” Now we are living in “the Time of Crisis, Vertigo Time,” which “is also the time of war. Of the war that hasn’t started yet. Or that has without our realizing. Or the war that never ended, to paraphrase the poet Natalie Diaz, and that somehow keeps beginning again.” What are points of orientation in this Vertigo Time? What can Palestine teach us in the U.S.?

BE: It seems cruel to ask them to teach us even as we continue to sponsor and support their oppression, but Palestinians have had to learn, over the last seventy years, how to survive and struggle on with the odds entirely against them—and not just survive but live and love and hold on to some fundamental humanity that the occupation is bent on destroying. That’s more or less the subject of The Way to the Spring, the costs of that kind of struggle, what it means for hope and despair to commingle so completely. I’m afraid there’s a lot we in the U.S. will have to learn about that. Our points of orientation remain one another. You hold on to the people who struggle alongside you, to the ancestors who struggled before you, to your children and grandchildren, who you hope will not have to.

BD: One reason this is an anxious present is that “the courses of action still deemed practical will usher us straight down the path that leads to our own deaths.” Perhaps it is because of your anarchist sympathies, with which you conclude the book, that you hesitate to prescribe alternative courses of action (your subtitle notwithstanding). I take it you have things in mind larger than asking your readers to switch from a large bank to a credit union, something grander you note under the heading of working to “dismantle our delusions”?

BE: Oh, yeah. I have in mind the end of capitalism. That’s been a goal of radical political thinkers for the better part of two centuries, but it seems less and less radical by the day. The transformation of the Earth’s atmosphere through the combustion of fossil fuels dates precisely to the birth of modern capitalism. The two are inextricably linked, and they are linked as well to the colonial and ultimately genocidal context in which they were born. That is one of the subjects of the book: how we arrived at a point in which a system that is demonstrably hostile to all life could dominate us so thoroughly.

BD: A live tension in the book is about writing itself, what it can do and how it can affirm or challenge power. You talk about how writing itself has long been tied to ruling cities and spaces, how it has long been a technology of domination, from the formation of the first cities to the foundations of anthropology. “If his presence, and his writing, caused harm to his ostensible subjects, [Claude] Lévi-Strauss did not wish to dwell on it,” you observe. “Better to highlight the violence of all writing, shrug, and move on. One of the things I am trying to do here is not ever shrug.” How is all writing violent? How does it condition our affect (whether or not we shrug)?

BE: I don’t think it is necessarily violent. This understanding of writing as inseparable from structures of domination—really, from the state—goes back at least to Rousseau, but Lévi-Strauss famously and forcefully, and I think dishonestly, articulated it in Tristes Tropiques. In the section you’re citing my point was to show how self-serving his argument was. Lévi-Strauss tells a story—he writes it—in which his obliviousness to the consequences of his own presence endangers the community he is ostensibly observing, ultimately causing it to break up. In his telling, though, this becomes a story about someone else’s—the community’s chief—irresponsible use of power, and about that chief’s attempt to use written language to shore up his control. It’s an extraordinary sleight of hand. Of course, it is Lévi-Strauss who is putting writing to that use, and in a much-quoted aside he pauses to suggest that written language has always been primarily a tool of domination, so what can you do? That’s the shrug that bothered me, because I think it’s bullshit. It’s a sophisticated but also a cowardly and evasive rhetorical move. Writing may have evolved in ancient Mesopotamia to record the contents of the royal storehouses, and it still may function more often than not in the service of the powerful, but it has also been used, time and again, as a tool of liberation. That, I think, is the challenge of literature.

BD: Can you comment on how you selected the sources you draw on in Desert Notebooks? You consider why the anthropologist James Mooney didn’t report in nuance about Wounded Knee: “Perhaps he knew that ethnological methods could only be applied to Indians. Whites got to speak for themselves. Perhaps, when it came to bullets flying, Mooney simply chose a side.” Many of the authors you cite are interested in turning ethnological methods around, in a certain sense. For instance, Walter Benjamin’s essay “Capitalism as Religion.”

BE: The selections were super organic: one text led me to another which led me to another, and they were frequently connected by surprising links. I was interested in writers who tackled, or failed to tackle, the questions I was trying to ask about the relationship between writing and power. Mooney wrote a courageously sympathetic account of the Ghost Dance, but when it came to Wounded Knee, he lined up on the side of his race. We see the same kind of thing all the time today, when in times of war or crisis liberal writers bang up against the limits of their moral imaginations and toe the usual nationalist lines.

BD: I once asked an employee at The Metropolitan Museum of Art how they acquired some Islamicate sculptures, and the employee named a donor. “By expropriating these objects and interpreting them, by owning them,” you write about similar practices in the British Museum, “they were taking possession of history itself. They were laying claim to time.” So I want to loop back to an earlier question: Is repatriation part of a corrective to time?

BE: It’s a start. And I suppose that the fact that there has been a sustained campaign to pressure museums to return treasures looted from former colonies suggests that that particular vision of history is already fraying and slipping out of the control of those who it benefited. It’s lucky that some things—sculptures, statuary, material artifacts—can be repatriated, but of course there’s so much that cannot, so many millions of lives that were and still are being broken by wars for empire. And there’s no easy corrective to that.

BD: I think ultimately your book is about how “humans have, at the brink of the abyss, stepped back and learned to live inside of time, and to hold each other there.” Do you want to say more about this?

BE: This may sound like a cop out, but I don’t want to. That’s something we will have to figure out together. Quite quickly, I might add.